Paul I in the early 1790s

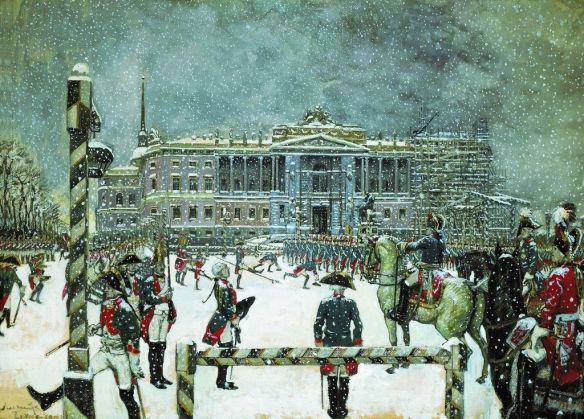

Military Parade of Emperor Paul in front of Mikhailovsky Castle painting by Alexandre Benois

The French Revolution had given new impetus to the demand for liberal reforms in Russia, but, more importantly, it rallied the strong reactionary elements around the empress. Talk of reform became treasonable and all hope of change vanished. Conditions in Russia continued to deteriorate alarmingly. Inflation, food shortages, the extravagances of the court, mounting military expenditures, and the underlying gangrene of serfdom combined to present the nation with a massive crisis. Russia needed an activist emperor, but forty-two-year-old Paul, who had succeeded Catherine, was unstable and impetuous.

Paul hated his mother. He blamed her for his father’s murder, and he bitterly resented the fact that she had usurped his throne for so many years. As much as possible, he rejected all that his mother had done. He shared Peter III’s hero worship of Frederick the Great and revered all things Prussian. He was obsessed with military parades and the paraphernalia of war. During the years when he was grand duke and heir to the throne, he had not been allowed to take part in state affairs. Virtually confined to his estate at Gatchina, he had spent his time drilling and parading his private army of 2,000 men. Now as emperor, he had the armies of the nation at his command.

St. Petersburg was transformed into a military camp. Army discipline became more savage. Men who were guilty of real or imagined mistakes were cruelly flogged. Paul further antagonized the army, and especially the regiments of guards, by introducing Prussian uniforms in place of the ones Peter the Great and Potemkin had designed.

The army and the parade ground defined Paul’s attitude toward the state. In his view, the emperor held the absolute power of a general over subjects, who were to be ordered about as though they were troops on parade. He regarded obedience and discipline as the basic needs of a healthy society. Apart from the regimentation he sought to impose, Russia began to suffer even more from the excessive centralization of all government functions in St. Petersburg.

Under Paul’s erratic rule, certain ukazy were issued to ease the burdens of the peasantry. A decree promulgated in April 1797, for example, laid down that landowners, some of whom exacted five or six days of labor a week from their serfs, should now require them to work only three days; the remaining three days belonged to the serfs for the cultivation of their own lands, and Sunday was for rest. However, it is doubtful this was ever enforced. The serfs had no means of recourse against landowners who ignored it. Paul, eager to limit the power of the upper classes, partially restored the right of the peasants to petition the throne with their grievances. But it was difficult to exercise this right, and landowners could still uproot their peasants and send them to Siberia. As if to negate these limited benefits, Paul insisted that unrest among the peasantry must be dealt with firmly. He issued a manifesto calling on all serfs to obey their masters without question.

At the same time, Paul antagonized the gentry by assailing privileges that Catherine had bestowed. In 1785, she had granted a charter guaranteeing them immunity from corporal punishments, payment of taxes, and deprivation of rank and estates except by judgment of their peers. He did not impose taxes on the gentry, but would “invite” them to contribute to the treasury for special purposes. He also required them to serve in the army. Refusal resulted in disgrace, banishment from court, and more serious punishments – often so savage that they caused severe injury or death. It was not uncommon for Paul, in one of his bouts of temper, to take away an offender’s noble rank – a crushing loss of privilege.

Foreign policy was also subject to Paul’s whims. He had criticized Catherine’s extensive military commitments and had vowed that on ascending the throne he would cancel them. But he was so strongly opposed to the revolutionary movement that he involved Russia in several European squabbles. He joined a coalition against France in 1799. He sent an army under the command of the brilliant Russian General Alexander Suvorov to join with the Austrian forces in northern Italy. But when the Austrians failed to support their allies sufficiently, relations between the two states quickly became strained. The combined armies nevertheless gained several victories in Italy and were preparing to invade France when Suvorov received orders to march on Switzerland without delay. In a feat of remarkable military derring, he led his army over the Alps by way of the St. Gotthard Pass. In Switzerland, however, relations between Russians and Austrians deteriorated further, and in 1800, Paul, angered by Austrian complaints about the disrespectful behavior of the Russian troops, suddenly canceled the accord and recalled Suvorov and his army. He next severed relations with Great Britain, mainly because the British failed to honor their promise to cede the island of Malta. By banning British ships from Russian ports, he inadvertently damaged Russia’s trade. He then joined the new Armed Neutrality with Sweden, Denmark, and Prussia to oppose British sea power, thus bringing Russian trade with its principal customer to an official standstill.

Meanwhile, Paul had reversed his earlier policy with France and decided that Napoleon was a necessary ally. He became enthusiastic about alliance with France, Austria, and Prussia for the purpose of partitioning Turkey and destroying British power. Russia and Britain now came close to war. In January 1801, the tsar formally annexed Georgia, which had been under divided Turkish and Persian suzerainty, and then he ordered a force of 23,000 Cossacks to proceed toward British India, which he dreamed of conquering.

Paul had antagonized the regular army and the gentry, the two main pillars of his throne, to the point where a palace revolution had become almost inevitable. The military governor of St. Petersburg, Count Peter Pahlen, was the leader of the final conspiracy. On March 11, 1801, he and several officers of the guard dined together and then set out for the Mikhailovsky Fortress, which Paul had ordered rebuilt for greater security. The sentries did not hesitate to admit the military governor and the officers with him. They made for the emperor’s bedchamber, but it appeared to be empty. Paul had heard them approaching and had hidden in the chimney of the fireplace, but one of the party noticed his dangling feet. They dragged him out, screaming for mercy. Someone struck him with a gold snuffbox and then strangled him with a scarf.