Suddenly it was the old glory days all over again – the quick surprise thrust, the reeling enemy, the Desert Fox leading from up front, the waves of consternation spreading through the opposing high command like ripples through a pond after the splash of a stone. Two panzer columns ripped through the thin American line, converged on a mountain gap called Kasserine Pass, brushed aside the force defending it, and poured through the pass into the American rear areas. Desperate counterattacks were methodically chewed up by German tanks and antitank guns.

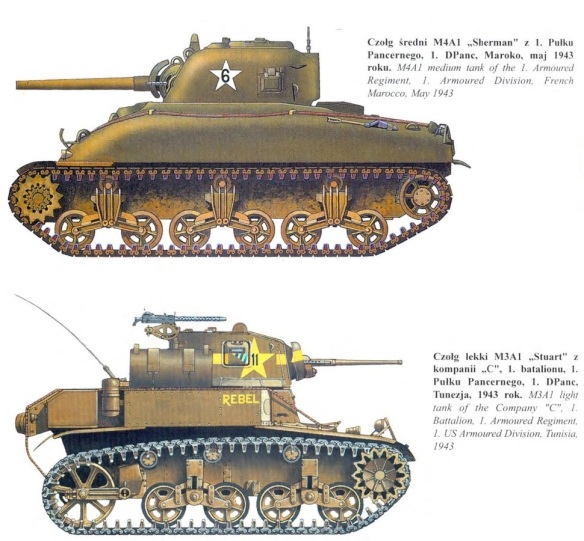

Collecting every unit they could lay hands on, the Allied commanders labored to plug the gap. Early in the Kasserine battle the green U.S. troops and their inexperienced commanders had been badly knocked about by Rommel’s desert veterans; now they began to dig in their heels stubbornly, particularly hard-fighting units of the U.S. 1st Armored Division. “They recovered very quickly after the first shock,” Rommel wrote. On February 22, unable to achieve a breakthrough, he pulled back through Kasserine Pass.

Two weeks later, Rommel tried a second attack, this time against the 8th Army near Mareth. But the old magic was gone. He was exhausted mentally and sick physically, and he mishandled the attack. His armor charged blindly and was cut to pieces by Montgomery’s antitank guns; some fifty tanks were lost, while the British lost but half a dozen. On March 9, 1943, his health broken, the Desert Fox left North Africa, never to return.

By the end of March, the Torch army’s losses at Kasserine Pass had been made good. Units were consolidated and inept commanders weeded out, and General Alexander arrived from Cairo to command the Allied ground forces. It was now a battle against time, a battle to end the campaign in Tunisia in time to assault Sicily and Italy that summer. If von Arnim could hold out for three or four months, however, no further Allied campaigns would be possible in 1943. This would suit Hitler very well indeed, giving him the chance to concentrate all his forces for one last mighty thrust at Russia.

The terrain facing the 8th Army in southern Tunisia was on the familiar desert pattern, but the rugged, mountainous north was something else entirely. In desert fighting, the armies were spread out and concealed in dust clouds, and the progress of a battle was seldom easy to follow. In northern Tunisia, on the other hand, it was usually possible to see the enemy positions clearly and to plot the course of the battle without difficulty. In the sector manned by the British 1st Army, for example, there was a long and bitter struggle for a piece of high ground known as Longstop Hill. The climactic British assault on Longstop, made in late April, looked like this to an eyewitness:

“Everything appeared to happen in miniature. The tanks climbing on Jebel Ang looked like toys. The infantry that crept across the uplands toward [the village of] Heidous were tiny dark dots, and when the mortar shells fell among them it was like drops of rain on a muddy puddle. Toy donkeys toiled up the tracks toward the mountain crests, and the Germans, too, were like toys, little animated figures that occasionally got up and ran or bobbed up out of holes in the ground between the shell explosions.”

As Longstop was being overrun, another equally bitter battle was being fought for Hill 609 in the American sector a few miles to the north. This high ground – named for its height in meters on the maps the Allies were using – was blocking the advance of the American 2nd Corps, commanded by Major General Omar Bradley. For four days, the fight for Hill 609 raged. Von Arnim’s stubborn infantrymen were dug into cracks and crevices on the stony heights, and their mortars and artillery dominated all the approaches to the hill.

“Seldom has an enemy contested a position more bitterly than did the Germans high on Hill 609,” wrote General Bradley. They rolled hand grenades down on the Americans clawing for a foothold on the steep slopes, and their strong points were taken only after hand-to-hand combat with pistols, knives, and fists. Each American gain was met by a vicious counterattack. Finally, Bradley ordered Sherman tanks forward to provide fire support. They nosed up to the foot of the hill and chipped away at the enemy positions with their seventy-five millimeter guns, their armor proof against the bullets and grenades showered down on them.

At last, on May 1, Hill 609 was encircled and the defenders hunted down. The capture was sweet revenge for the U.S. 34th Infantry Division. The 34th had been badly mauled by the Afrika Korps at Kasserine Pass in February, losing both its reputation and its self-respect in the process. Now it regained both, with interest.

Already, Montgomery, in a masterful display of battlefield tactics, had forced the Mareth Line and linked up with the Torch army. The loss of Longstop and Hill 609, combined with heavy pressure from the 8th Army, drove von Arnim back to his final line of defense overlooking the approaches to Tunis and Bizerte. Last-minute attempts to fly in reinforcements from Sicily met with disaster. Scores of Junkers transports and mammoth six-engined Messerschmitt troop carriers were knocked into the sea by Allied fighters.

On May 6, behind a tremendous artillery barrage and a bombing attack, the last German line was blown open. Tanks burst through like water through a broken dam. “In scores, in hundreds, this vast procession of steel lizards went grumbling and lurching and swaying up the Tunis road,” wrote correspondent Moorehead. The next day, Tunis itself was in sight. It was especially fitting that the Desert Rats of the British 7th Armored Division, their famous red jerboa emblem still decorating their vehicles, were among the first to enter the city. The Desert Rats were bringing to an end the long campaign they had begun under O’Connor in those far-off days of 1940.

That same day, the Americans reached Bizerte. A force of Grant tanks swept into the city, exchanging fire with snipers and the German rear guard. A crewman of one of the tanks described the scene in a letter to his family.

“By this time it was getting very hot and stuffy in the tank,” he wrote, “so we climbed out and took a smoke. . . . Then a Frenchman comes up with a bottle of wine and we all had a smoke and drank the bottle of wine. A shell lands behind the tank and sort of makes us mad, so we get back in and start shooting away again – and the people just standing there on the sidewalk. Every time George would shoot the seventy-five, plaster would fall down from all the buildings around, but they didn’t seem to mind that, they were so glad to see us. . . .”

Axis troops were now surrendering in droves. Many tried to flee to Cape Bon, a finger of land jutting out into the Mediterranean, but when they saw that there were no ships or planes to carry them across to Sicily, they too gave themselves up. As the men of his Afrika Korps marched into captivity, Rommel was with Hitler in Berlin. “I should have listened to you before,” the dejected Führer told him, “but I suppose it’s too late now. It will soon be all over in Tunisia.”

It was all over on May 13, 1943. Close to 275,000 Axis troops were captured in the last week of battle. They stacked their weapons and came into Allied lines in endless, orderly columns of trucks. Almost none escaped. “It is my duty to report that the Tunisian campaign is over,” General Alexander cabled Prime Minister Churchill. “All enemy resistance has ceased. We are the masters of the North African shores.”

The crushing defeat in North Africa was the beginning of the end for the Axis partners. Before the year was out, Sicily and Italy were invaded, and massive Russian attacks rolled back the Germans on the eastern front. In June 1944, the Allies attacked across the English Channel to win a foothold on the Normandy shores; by fall, France was liberated and the battle for Germany had begun.

For some, North Africa was the first step on the road to military fame. Eisenhower became supreme commander of Allied forces in Europe, with Montgomery the head of his ground forces. Alexander commanded the forces in the Mediterranean theater. American generals such as Bradley, bloodied in Tunisia, went on to carve important niches for themselves in the European campaign. But for others the desert war was the climax of their military careers. Wavell and Auchinleck, for example, later served in relative obscurity in the Far East; General Ritchie ended up as a corps commander in Europe under Montgomery.

For Erwin Rommel, who put such a unique, personal stamp on the desert war, the future brought only disillusionment and doom. In July 1944, while commanding the German forces in Normandy, he was gravely wounded in an air attack. A few days later, a group of generals, convinced that Hitler was insane and dragging Germany down to destruction in a war already lost, tried to kill the Führer by planting a bomb in his headquarters. Rommel, who had long since come to despise Hitler, knew of the plot to overthrow him but took no part in it. Nor did he know that the conspirators planned to name him head of state to negotiate peace if they succeeded. But Hitler survived, and in the purge that followed, Rommel was implicated.

He was at his home recovering from his wounds when Hitler’s police came. They gave him the choice of suicide by poison or a public execution, with its disgrace to his family and his memory. He chose to kill himself. His son, Manfred, saw the body soon afterward. “My father lay on a camp bed in his brown Africa uniform,” he said, “a look of contempt on his face.” The German people were told that the Desert Fox had died of the wounds suffered in Normandy, and on October 18, 1944, he was given a hero’s funeral. Seven months later, Hitler also killed himself, and Germany lay defeated and in ruins.