American Armored Doctrine And Equipment II ➡️

American armored doctrine and equipment were first tested in combat in North Africa. One of the first illusions to evaporate in the heat of battle was the effectiveness of the light tank.

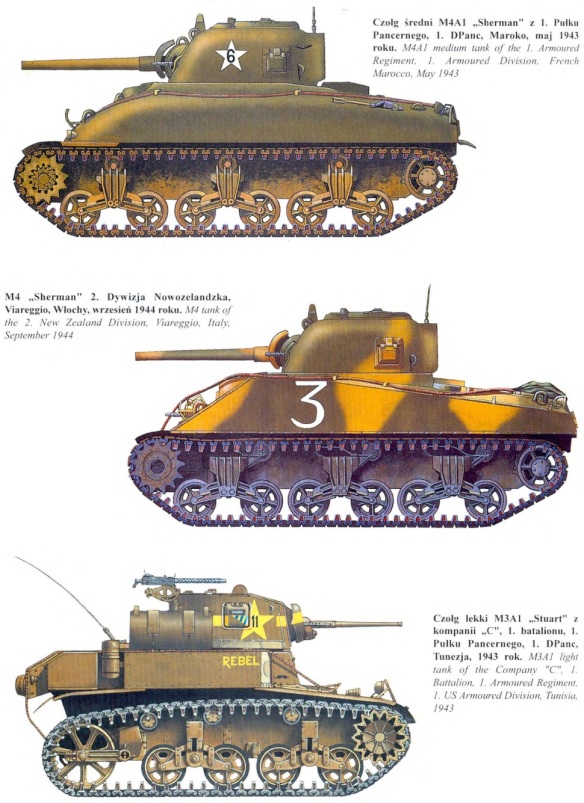

On November 26, 1942, Lieutenant Freeland A. Daubin and his platoon of M3 light tanks from Company A, 1st Battalion, 1st Armored Regiment, 1st Armored Division, fought the first engagement of the war between American and German tanks. Daubin and his crew entered the battle with a “great and abiding faith in the prowess of the 37mm ‘cannon’” with which their tank was armed. When a German Panzerkampfwagen (Pzkw)IV came into range, Daubin confidently ordered his crew to begin firing. His confidence soon turned to panic:

The 37mm gun of the little American M3 light tank popped and snapped like an angry cap pistol…. The Jerry seemed annoyed by these attentions. Questing about with his incredibly long, bell-snouted, “souped-up” 75mm Kw K40 rifle, the German commander spotted his heckler. Deciding to do the sporting thing and lessen the extreme range, he leisurely commenced closing the 140 yard gap between himself and the light tank, but keeping his thicker, sloping frontal plates turned squarely to the hail of 37mm fire.

The crew of the M3 redoubled the serving of their piece. The loader crammed the little projectiles into the breech and the commander (who was also the gunner) squirted them at the foe…. The German shed sparks like a power-driven grindstone. In a frenzy of desperation and fading faith in their highly-touted weapon, the M3 crew pumped more than eighteen rounds at the Jerry while it came in. Through the scope sight the tracer could be seen to hit, then glance straight up. Popcorn balls thrown by Little Bo Peep would have been just as effective.

One hit from the German’s high-velocity 75-mm gun ended the contest. As Daubin lay bleeding on the floor of a wadi, he watched the Germans destroy five more M3s. Fortunately, Major William R. Tuck, commander of Company B, was able to maneuver his light tanks to the flanks and rear of the enemy force. Firing at close range, the 37-mm guns knocked out seven enemy tanks before the Germans withdrew. Tuck’s tactical innovation—maneuvering to engage the less heavily armored sides and rear of a German tank—was one that American tankers came to rely on heavily.

As the campaign proceeded in North Africa, General Devers, commanding general of the armored force, arrived from Fort Knox. Devers headed a mission “to examine the problems of Armored Force units in the European Theater of Operations.” Overseas from December 14, 1942, until January 25, 1943, Devers found few flaws in armored force equipment and claimed that “the M-4 (General Sherman) [was] the best tank on the battlefield.”

The ordnance annex to his report probably fueled Devers’s enthusiasm. British Generals R. L. McCreery and C. W. Norman were noted to have said that the “American M3 tanks had stopped the Germans at the El Alamein line and that the M4 tanks defeated the Germans in the break through.” The report cited interviews with British soldiers that led to the blanket conclusion that the M4 tank with its 75-mm gun “could easily defeat any German tank.” The British tank crews also stressed that they preferred to use the M4 in a “hull-down,” or defensive, position. Thus, the M4s were concealed and largely protected from return fire. The report further noted that the 75-mm armor-piercing (AP) ammunition “was found capable of penetrating all German tanks at ranges as great as 2,500 yards.”

British soldiers also commented that the M4, with its high explosive (HE) shell, destroyed antitank guns at ranges up to 3,500 yards. Range was particularly important in North Africa, because the German 88-mm antiaircraft gun, also used in an antitank role, was the most feared tank killer on the battlefield. The fragmentation of the HE round killed the German crews servicing the 88s, because they had virtually no armor protection. The British tanks, which fired only AP rounds designed to penetrate armor, were not effective against personnel. Consequently, British tank crews had not been able to silence the 88s before the advent of the M4. This report must have been particularly encouraging to the Americans personnel were a target—because the M4 had been designed to handle. Finally, the ordnance team reported that it had interviewed a number of Americans. Incredibly, Lieutenant Daubin’s battalion commander, Lieutenant Colonel John K. Waters, had “praised the 37mm gun and stated that it gave good results in battle destroying the German Mark 3 and Mark 4 tanks at about 300 yards.” Either the ordnance officers were hearing what they wanted to hear or Colonel Waters was not aware of how his battalion felt about its M3 tanks.

Devers was also pleased with Armored Force tactics. He noted that the British Eighth Army had used “the same tactical principles and doctrines taught by the Armored Force” with great success, but Devers did not find everything to his liking. He noted that the “present war is definitely one of guns” and that successful offensive operations were those that integrated “air, tanks, and artillery,” while a viable defense required “air, concealed antitank guns, and artillery.” Devers then reasserted his earlier arguments against tank destroyers, stating that “the separate tank destroyer is not a practical concept on the battlefield.” In Devers’s opinion, “the weapon to beat a tank is a better tank. Sooner or later the issue between ground forces is settled in an armored battle—tank against tank.”

Shortly after the Devers mission departed the combat zone, American armored forces experienced blitzkrieg firsthand. On February 14 General Curt von Arnim attacked FaÏd Pass and overran the haphazard American defenses. The 1st Armored Division’s Combat Command C counterattacked and was soundly defeated by the veteran Germans. As von Arnim continued his advance, the Americans retreated in disarray. On February 19 Field Marshal Erwin Rommel attacked American positions at Kasserine Pass, and the next day the panzers broke through. Fortunately for the Allies, the Germans lacked sufficient resources to exploit their offensive successes. The Allies poured in men and matériel to bolster their defenses and checked the German advance.

For the Americans, their first experiences against a determined and professional German offensive were unnerving and humiliating: “American armor was employed piecemeal, not massed…. American tankers had been outwitted by veteran Germans. The Army Air Force had been ineffectively coordinated…. Worst of all, American troops had fled in panic before the enemy.” Eisenhower, believing they “had proven to be indecisive in crisis,” relieved the II Corps commander, Major General Lloyd R. Fredendall, and the 1st Armored Division commander, Major General Orlando Ward.

The Americans attributed the defeat at Kasserine to “green troops” and poor leadership. The War Department believed that “failures or tactical reverses…resulted from misapplication of…principles, or from lack of judgment and flexibility in their application.” The Army applied the traditional correctives of training, discipline, and leadership—all of which were abundantly supplied when General Patton replaced Fredendall as the II Corps commander. Unfortunately, obvious breakdowns in the human dimension obscured doctrinal and technological deficiencies.

General McNair, commanding general of the Army ground forces, received a copy of Devers’s report and on February 19 wrote a letter to Major General A. D. Bruce, commander of the Tank Destroyer Center at Camp Hood, Texas. McNair stated that he had discussed with Secretary of War Stimson “that Devers seemed not to care much about tank destroyers.” McNair then reassured Bruce that Stimson was still on their side: “The Secretary bounced right back with the statement that he was one of the original backers of the tank destroyers, and that he would have to have Devers in for a talk on the question.” McNair also believed that American combat experiences verified his position and wrote to Bruce that he was “confident that the track we are on—in both tank destroyers and antiaircraft—is both sound and not in jeopardy.” He was also convinced that “developments in Africa only serve to demonstrate the soundness of this conception.” Indeed, he believed that “if they had piled in tank destroyers instead of armored units, the 1st Armored Division would be still intact.”

By September 1943 the lessons from North Africa had been applied to the American armored forces. The adaptations were evolutionary: The structure of the armored division changed to a more balanced organization whose combat elements included three tank battalions, three armored infantry battalions, and three armored field artillery battalions. These units were combined or “task organized” for operations and controlled by three combat command headquarters (A, B, and Reserve). The thick German antitank defenses, consisting of guns and mines, had discredited the notion of unsupported tank attacks and established the need for more infantry. The number of light tanks in the divisions was significantly reduced. All three tank battalions had three medium tank companies and only one light tank company, which was primarily used for reconnaissance.

Armored doctrine remained largely unchanged. On September 29, 1943, the Army ground forces issued a field manual that reaffirmed the exploitation role of the armored division. Infantry divisions were to make holes in enemy lines so that “the armored division may pass through the gap created and exploit the success.” Exploitation was defined as “an attack to destroy enemy installations or formations, to seize critical terrain.” Furthermore, the manual again clarified that “the primary role of the tank is to destroy enemy personnel and automatic weapons.” The armament of American tanks supported this mission: “The main purpose of the tank cannon is to permit the tank to overcome enemy resistance and reach vital rear areas, where the tank machine guns may be used most advantageously.” The publication also stated that “antimechanized protection,” if required, would be provided by attaching tank destroyer battalions.

In May 1943 General Devers departed the armored force to command the European theater of operations. Major General Alvan C. Gillem, an infantryman, replaced Devers, which probably explains the increased emphasis on medium tanks and infantry support in the armored division. Gillem brought his own assumptions about armored warfare. In September he reversed his earlier decision to arm all future M4 tanks with more powerful 76-mm guns. In keeping with vintage infantry tank doctrine, he believed that the 75-mm cannon had a better high explosive shell than the 76-mm cannon. Therefore, the 75-mm cannon-equipped M4 was a better weapon against the targets that tanks were doctrinally designed to defeat. Gillem believed that only one-third of the Shermans should have the better antitank gun.

McNair supported Gillem’s decision to use the 75-mm cannon, and when Devers cabled from Europe to request that the development of the T26 tank, armed with a 90-mm gun, be given highest priority to counter German tank developments, McNair’s response was predictable: “I see no reason to alter our previous stand…essentially that we should defeat Germany by use of the M-4 series of medium tanks. There has been no factual developments [sic] overseas, so far as I know to challenge the superiority of the M-4.”

McNair was firmly committed to the tank destroyer concept. He believed that the Americans had experienced nothing in combat against the Germans that justified heavier tanks, with their attendant mobility and overseas shipping problems. American forces had encountered German Pzkw V Panthers and Pzkw VI Tigers in Italy and had been able to stop them with seemingly little difficulty. Since he controlled the promulgation of American armored and tank destroyer doctrine, his opinions were in effect law, and he was not alone in his conclusions.

McNair’s position on tank and antitank missions was shared by many ground officers. In April 1944 General Patton sent McNair a copy of his “Letter of Instruction No.2,” in which Patton gave his views—in accord with McNair’s—on armored tactics. Patton stressed that “the primary mission of armored units is the attacking of infantry and artillery. The enemy’s rear is the happy hunting ground for armor.”

Although the doctrinal debate was relatively tame, the Ordnance Department and the Army Ground Forces squabbled intensely over tank technology. This friction closely resembled the prewar disputes between the chief of ordnance and the chief of infantry. The Ordnance Department wanted to standardize heavier armored and armed tanks to remain competitive with new German designs. The Army Ground Forces did not interfere in ordnance development programs but blocked standardization in most cases. The Army Ground Forces believed that if the Germans developed a significantly more powerful tank, the appropriate technological response was not to abandon the proven M4 design but to develop more powerful tank destroyers. Consequently, the most powerful tank available to American troops when they landed at Normandy was the M4 with a 76-mm gun.

Even after the invasion the M4 initially seemed adequate to deal with German armor because long-range engagements were rare in the thick hedgerow country. Nevertheless, the difficulty of defeating German armor was becoming a concern. Soon after D day, the First Army conducted test firings against a captured Panther. The results were alarming. Only the 90-mm antitank gun and the 105-mm howitzer could penetrate the front glacis of the German tank—and even these guns were effective only at close ranges.

Particularly disconcerting was the ineffectiveness of the new 76-mm gun mounted on the M4 medium tank. General Omar N. Bradley, commander of the Twelfth Army Group, noted that “this new weapon often scuffed rather than penetrated the enemy’s armor.” In July 1944 General Dwight Eisenhower was dismayed when Bradley told him of the failings of the 76-mm gun: “You mean our 76 won’t knock these Panthers out? Why, I thought it was going to be the wonder gun of the war.” When Bradley responded that it was better than the 75-mm gun but still not good enough, Eisenhower was irate: “Why is it that I am always the last to hear about this stuff? Ordnance told me this 76 would take care of anything the German had. Now I find you can’t knock out a damn thing with it.”

Unfortunately, little could be done to correct the inadequacy of American tanks in the summer of 1944. Following the breakout and the drive against Germany, the deficiencies of the Sherman and the inappropriateness of tank destroyer doctrine became increasingly obvious. The M4 Sherman, even with its 76-mm gun and the new hypervelocity armor-piercing (HVAP) ammunition, could not take on Panthers or Tigers head-to-head—nor could any other American gun at ranges outside the engagement envelope of German tanks.

American tankers had to employ the tactics learned in the North African desert of maneuvering to attack the more vulnerable sides and rear of the German tanks. The costs were high. One battalion of the 2d Armored Division lost 51 percent of its men and 70 percent of its tanks in two weeks of action. American soldiers began to lose faith in their tanks—with good reason. Sergeant Thomas P. Welborn explained the risks in trying to overwhelm a German Panther:

On 5 August in the vicinity of St. Sever Calvados, France, [I] witnessed a German Mark V tank knock out three M4 and three M5 tanks during and after being hit by at least fifteen rounds of 75mm APC from a distance of approximately 700 yards. All of these shells had ricochetted, with the exception of a sixteenth round which finally put the Mark V tank out of action.

The closer the Allies got to Germany, the more determined the German resistance became. In mid-November the 1st Battalion, 67th Armored Regiment, 2d Armored Division, was on the Roer River plain near Puffendorf, Germany, preparing to attack toward Gereonsweiler. Suddenly, between twenty and thirty German tanks, including Tigers and Panthers, opened fire. As the Shermans tried to maneuver for flank shots, they became mired in the muddy ground and were picked off. In only two days the 2d Armored Division suffered 363 casualties and lost 57 tanks. Most of these losses occurred at Puffendorf. It had been an uneven exchange; the 1st Battalion, 67th Armored Regiment, claimed only two German tanks destroyed by Shermans and two by M36 tank destroyers. Corporal James A. Miller expressed the overwhelming sense of fear and frustration the American tank crews felt:

One morning in Puffendorf, Germany, about daylight I saw several German tanks coming across the field toward us; we all opened fire on them, but we had just about as well have fired our shots straight up in the air for all the [g]ood we could do. Every round would bounce off and wouldn’t do a bit of damage. I fired at one 800 yards away, he had his side toward me. I hit him from the lap of the turret to the bottom and from the front of the tank to the back directly in the side but he never halted. I fired one hundred and eighty four rounds at them and I hit at least five of them several times. In my opinion if we had a gun with plenty of muzzle velocity we would have wiped them out. We out-gunned them but our guns were worthless.