The Fleet of the League of Corinth

One of the burdens placed on the members of the League of Corinth after the allied Greek defeat at Chaeronea, and subsequent recognition of Macedonian hegemony, was to supply ships to aid the war effort. This fleet was established in 336 or shortly before, and its main purpose was to act as support to the land operations being conducted by the field army. This support largely involved them acting as transports and maintaining the lines of supply and communication with Macedonia and Greece. The fleet must have been remarkably heterogeneous and was of moderate size, consisting of 160 ships of which a mere 20 were supplied by the strongest naval power in Greece: Athens. At this time the Athenians had around 300 ships in commission; the supply of only 20 is perhaps suggestive of their level of enthusiasm for Alexander’s expedition. Many of the smaller city-states would have supplied the merest handful. Arrian tells us that the fleet was untrained, each member state evidently only sending the worst ships and sailors at its disposal, simply to honour a commitment. The resulting fleet was effectively useless as a fighting force; it was poorly trained and consisted of large numbers of contingents who had never fought as a cohesive unit before. Coupled to this was Alexander’s total lack of knowledge of naval operations. Realistically it would have been impossible for Alexander to have operated with anything but the most basic tactics. This is strongly suggested by Arrian when he has Alexander, in debate with Parmenio as to whether to engage the Persian fleet at sea, saying that he would ‘not risk making a present to the Persians of all the skill and courage of his men’.

This can only be a reference to the potential loss of Macedonian troops, not Greek sailors, and suggests that Alexander’s naval tactics would rely on boarding Persian ships and fighting hand to hand. This would effectively be to fight a land battle at sea. These tactics are not wholly surprising in a commander who had no experience at all of naval warfare, either directly or through Philip’s tutelage. The tactics that Alexander likely would have employed are, interestingly, exactly how the Vikings fought their naval battles.

Despite the evidently poor quality of vessels supplied by his allies, Alexander’s Greek fleet had proved itself of greater use than simply for logistics and transport alone. Whilst Alexander was besieging the city of Miletus by land, the Persian fleet of some 400 vessels was heading north to relieve it. If the Persians had arrived, the city could presumably have held out against the Macedonians almost indefinitely, as reinforcements and supplies could easily be transported by sea. Nicanor, commander of Alexander’s Greek fleet, arrived three days before the Persians, however, and anchored his vessels off the Milesian coast on the island of Lade. The Persian fleet, unable to find any port suitable to meet its supply needs, and seemingly unable or unwilling to engage the Greeks in these narrow waters, set sail south again. Thus Alexander’s fleet had proved, quite convincingly, that, despite his unwillingness to offer a naval battle, his fleet could still be of considerable military usefulness. This makes the subsequent decision to disband it even more baffling.

Soon after the capture of Miletus, and before the commencement of operations at Halicarnassus, Alexander made one of the most debated decisions of his career: he disbanded his fleet. Arrian gives us five reasons:

• Lack of money.

• The Persian navy was far superior to Alexander’s own.

• Alexander was unwilling to risk any losses, in ships or men, in a naval engagement.

• Alexander believed that he no longer needed a fleet as he was now master of the continent of Asia.

• He intended to defeat the Persian navy on land by depriving it of its ports.

Lack of money is the reason most commonly accepted by modern historians as the major factor in Alexander’s decision; it is also the only reason cited by Diodorus. The conclusion that the decision was financially motivated is flawed for two reasons. Firstly, the fleet was supplied by the member states of the League of Corinth; it is therefore reasonable to assume that the cost of their upkeep would also fall on these states and not on Alexander. The fleet would, effectively, have cost him almost nothing to maintain. Secondly, Alexander should not have been short of funds at this point. Just a few months later at Gordium, during the winter of 334/3, Alexander invested 500 talents on raising a new fleet and 600 talents were allotted to pay for the upkeep of garrisons on the Greek mainland. There seems no reason why Alexander’s financial position should have improved so drastically in just a few short months, we know of no major Persian treasuries in this area that had fallen into Alexander’s hands.

Arrian is correct to say that the Persian fleet was superior to Alexander’s, both in numbers and quality. This is not a reason to demobilize the fleet, however, as this would leave the islands and the mainland defenceless from a naval assault. Miletus had also shown Alexander that a fleet was tactically useful even if he did not offer battle to the Persians. This lack of quality and numbers would be more of an argument for increasing investment in the fleet, rather than ridding himself of it.

Arrian’s second and third points are certainly linked; Alexander was unwilling to offer a naval battle because of the potential ramifications. His strategy would involve a heavy reliance on marines, most likely the hypaspists, given that these were the most versatile heavy infantry troops that he commanded. These were also the troops that were assigned to the final naval assault against Tyre, so it is most likely that they would have been chosen for this mission too. Yet he needed every one of these troops for the land campaign, making a naval campaign even more problematic. Any defeat could also have caused political problems back in Greece too; it would have been an open invitation for general rebellion throughout Greece.

The suggestion by Arrian that Alexander did not need a fleet, as he already controlled the whole continent, is extraordinary and obviously not true. Even if we take Arrian to be referring to Asia Minor, rather than the whole of Asia, then it still was nowhere near true. Besides, there was now nothing stopping the Persians from attacking Alexander’s forces in the rear, which they in fact did at Tenedos. This was a tactic that should have been employed far more effectively than it ever was by the Persians.

This strategy of defeating the Persian navy on land is famous, and, on the surface, fairly sound. In the ancient world warships could not carry any great quantity of supplies and so had to dock at a friendly port every night to resupply themselves with food and fresh water. It is also true that this strategy ultimately worked: the Persian fleet did collapse as Alexander captured key cities on the Phoenician coast. Yet the strategy had at least two serious flaws. The first was that a competent commander, as Memnon surely was, had a free hand to act as he wished in the Aegean; to overrun all of the islands and carry the fight to the mainland where several states would more than likely have revolted given the opportunity. The second was that it does not take any account of the fact that a significant portion of the Persian fleet was from Cyprus, which would theoretically have been unaffected by this strategy; although these ships would still have needed mainland ports in order to operate, they would still be loyal to the Persians and able to harass Alexander’s rear with Alexander having no possibility of using his land army to capture their ports. Alexander essentially relied upon luck to overcome these two problems, which was very uncharacteristic. His planning was usually far more meticulous than this and his strategies were well thought out, which leads me to conclude that his decision here was not a purely tactical or strategic one, but something rather different.

If the decision to disband the fleet was not taken on military grounds, nor forced upon him by lack of funds or any of the other reasons Arrian cites, why did he make this decision? I suspect that the truth lies in something that Arrian comes close to mentioning. He points out that any loss in battle could lead to disaffection and potential rebellion at home, bringing up the question of loyalty. The allied troops with the army were loyal to Alexander, although this could have been because of a fear of reprisals at home if they had rebelled. It could also have been because of the presence of thousands of heavily armed, battle-hardened Macedonians. The fleet would very quickly have been far away from the location of the king or the army, so Alexander’s personality and influence would have had far less of an impact on them and the opportunity for disloyalty would have been exponentially greater, as well as being far easier to act upon. The fact that he retained the 20 Athenian vessels is an indication that he wanted to try to retain some specifically Athenian hostages, but 160 vessels was too great a risk. It is interesting to note that all Alexander ever got from the great naval power of Athens were these 20 vessels along with 200 cavalry; these 20 vessels and their crew, then, were important hostages against the good behaviour of Athens.

The Fleet of Proteas

We know very little about this fleet, or indeed its commander, Proteas. We do know that whilst Alexander was at Gordium in the winter of 334/3, Antipater gave orders for the reconstruction of a Greek fleet. The fleet was raised principally on the island of Euboea and in the Peloponnese, and its primary purpose was to act as a defensive force against the possibility of Persian naval action against the islands or even the mainland. We know very little about the size of this fleet: Arrian simply says ‘a number of warships’ and the only evidence we have of it in action involved fifteen ships attacking a force of ten Persian vessels off the island of Siphnos. The fleet seems to have been in commission only until 332.

The Fleet of Hegelochus and Amphoterus

There is only one reference in Arrian to the construction of a Macedonian national fleet, but we know from Curtius that whilst Alexander was marching between Gordium and Ancyra in the summer of 333 he invested 500 talents in the construction of just such a fleet. This fleet was led by Hegelochus and Amphoterus, but it is evident from Arrian that Hegelochus was in supreme command. Curtius tells us specifically that the former was in charge of the troops and the latter was responsible for the ships and therefore, presumably, their crews. It seems a slight contradiction that the commander of the naval element of a fleet was subordinate to the commander of the marines, but in reality none existed. It was not uncommon in the ancient world for this to be the arrangement and it is even less surprising when we consider the wider situation with Alexander, in which the army was the totally dominant military force. We also know, however, that Amphoterus was capable of acting independently when assignments arose: for example, he was sent to Lesbos, Chios and Cos at the head of a detachment of the fleet in 332. When the Macedonian fleet joined Alexander in Egypt during the winter of 332/1 Hegelochus was reassigned, but we do not know where to. At this time Amphoterus assumed command of both the ships and the marines. The fleet then appears to have been operating off Crete and the Peloponnese. The fleet was decommissioned in 331.

The Cypro-Phoenician Fleet

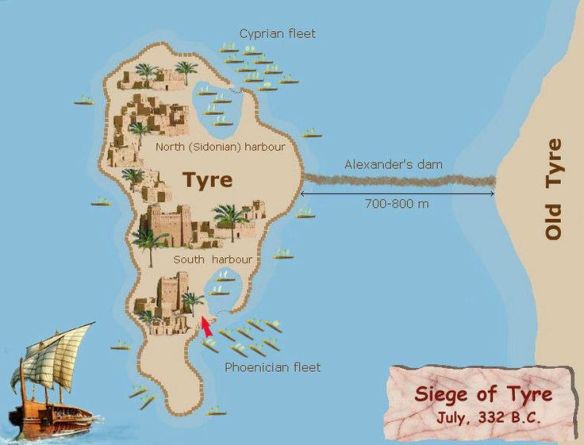

During the siege of Tyre in 333, soon after the mole was partially destroyed by the Tyrian fireship, Alexander along with his hypaspists and Agrianians set off on a mission to Sidon. Arrian tells us that this mission was ‘in order to assemble there all the warships he possessed’. It is unclear what this line actually means. It could be that Alexander intended to summon his Greek and Macedonian fleets to him; if this were the case, however, there was no need to travel to Sidon, and secondly there is no evidence that any such summons was issued or acted upon by the fleets.

It is perhaps more likely that Alexander believed quite simply that, as he now possessed the ports of Sidon and Byblos, along with many others, he also owned their fleets; he therefore travelled to Sidon to await their arrival home at the end of the campaigning season. Given the slow rate at which news was disseminated in the ancient world, news of the Persian defeat at Issus in November 333 may not have reached the fleet until after the end of the sailing season, so the Phoenician and Cypriot contingents were simply in no position to defect to Alexander until early April. By the time the Phoenician fleet arrived home, the siege of Tyre had been under way for two months. Alexander’s military presence in Sidon would ensure that there would be no difficulty with his taking personal possession of the fleet.

Arrian gives us a quite detailed account of the numbers of ships Alexander acquired: the contingents of Aradus, Byblos and Sidon accounted for a total of about eighty Phoenician vessels. At around the same time he was joined by a detachment ‘from Rhodes and nine other vessels, three from Soli and Mallus, ten from Lycia and a fifty-oared galley from Macedon’. Soon after the news of the Persian defeat at Issus had reached Cyprus, the Cypriot kings also decided to join Alexander at Sidon: their fleet alone totalled some 120 ships. Arrian’s total of 224 ships at Sidon generally agrees with Plutarch’s figure of 200 and Curtius’ claim that 190 ships took part in the surprise attack on Tyre.

The acquisition of the Cypro-Phoenician fleet was undoubtedly the turning point in the siege of Tyre: before this Alexander had no effective fleet and therefore no real means of countering Tyrian naval action against him. This fleet assured that he could probe the outer defences of the city from all directions. This ability to attack from a number of positions and directions simultaneously was another hallmark strategy of Alexander. Even in his set-piece battles we can see his desire to have the Companion Cavalry attack the Persian centre from the right, at the same time as the heavy infantry was attacking from the front. Alexander realized the benefit of such tactics very early during his career and applied it to every possible situation. The ultimate breakthrough came when a group of hypaspists, operating as marines, penetrated the walls at the southern tip of the fortress, not as a direct result of the construction of the mole. The troops on the mole would have had the effect of diverting some of the defenders away from the southern section of the walls, as would the fleet that was operating around the whole perimeter of the besieged city.