THE UTAH (MORMON) WAR, 1857–1858

Despite his brilliance at Monterrey and, later, at Buena Vista, Johnston was not commissioned in the regular army, and he left Mexico when his term of service in the volunteers expired. He settled with his wife in Brazoria County, Texas, on a plantation he called China Grove, which he struggled to coax into profitable productivity. Once again, however, penury and despair encroached, so that when his former commanding officer, Zachary Taylor, having been elected president of the United States in November 1848, offered him a regular U.S. Army commission as a major in December 1849, he took it. He took it, even though the position—paymaster—was hardly one he relished. His assignment was to service the far-flung military outposts on the Indian frontier of Texas. It was dangerous work, and it was grueling. During each of the five years he held the post of paymaster, he traveled more than four thousand miles, transporting, accounting for, and distributing pay.

In 1855, Jefferson Davis, serving as secretary of war under President Franklin Pierce, arranged for Johnston to be named commanding colonel of the newly authorized 2nd U.S. Cavalry with Robert E. Lee as his second in command. Indeed, for this elite regiment, Davis cherry-picked Southern officers he believed would break with the U.S. Army in the event of a civil war. In effect, Davis was laying the foundation on which an army of rebellion might be quickly raised.

In 1856, Johnston was also named commanding officer of the Department of Texas, and the following year he was tasked with leading a contingent of 2,500 troops from Texas to suppress a Mormon uprising in Utah after the so-called Mountain Meadows Massacre, in which Mormon zealots had killed 123 non-Mormon settlers. Against all expectation, Johnston proved to be a model of restraint in dealing with the Mormons and, without further bloodshed, was instrumental in establishing, pursuant to President James Buchanan’s orders, a non-Mormon government that restored federal authority in the territory. In recognition of his service, he received a brevet promotion to brigadier general late in 1857. Some even believed his display of diplomacy warranted something more, and his name was bandied about as a possible nominee for president on the Democratic ticket for 1860. Protesting that others were “more capable and more fit” for the office, he put a quick end to the talk.

OUTBREAK OF THE CIVIL WAR

Johnston commanded the Department of Utah from 1858 to 1860, returned briefly to Kentucky, and then, on December 21, 1860, sailed to California to assume his new command as head of the Department of the Pacific. As war clouds gathered, he sorted out his loyalties. Opposed to secession, he was nevertheless a believer in the rightness of slavery, and he decided that any attempt to end the “peculiar institution” by federal force constituted tyranny and invasion. Still, when Southern sympathizers called on him at his San Francisco headquarters to ask for his cooperation in capturing strategic facilities if and when war erupted, Johnston replied that he intended to “defend the property of the United States with every resource at my command, and with the last drop of blood in my body.” Similarly, when Governor John Downey of California questioned him about his intentions, Johnston replied that he had “spent the greater part of his life” in service to his country and “while I hold her commission I shall serve her honorably and faithfully. I shall protect her public property, and not a cartridge or percussion-cap shall pass to any enemy while I am here as her representative.”

In the end, it was General-in-Chief Winfield Scott who made the first move to sever Johnston from the army. Although he believed Johnston was an honorable man, he knew which way his cultural and political allegiances leaned, and he sent Brigadier General Edwin Sumner to relieve Johnston as commander of the Department of the Pacific, ordering him to leave California and to report to Washington. Instead of following that order, however, Johnston resigned his commission shortly after news reached him that Texas had seceded from the Union on February 1, 1861. He moved to Los Angeles and took up residence with some relatives. Remaining there until May, when the War Department officially accepted his resignation, Johnston fled likely arrest by local Union officials, enlisted as a private in the pro-Confederate Los Angeles Mounted Rifles, and rode with them to Texas and the Confederate Territory of Arizona, which he reached on July 4, 1861. From here, he set out on the long journey east to Richmond, Virginia, arriving about September 1, 1861.

Welcoming Johnston to the capital, President Davis informed him that he had been named one of the first five full generals in the Provisional Army of the Confederacy and held rank second only to Samuel Cooper. His assignment, Davis told him, was to command Military Department Number 2—the Western Department—which encompassed Kentucky, Tennessee, Missouri, Kansas, Arkansas, and western Mississippi.

The daunting mission that faced him was to raise, organize, and command the Army of Mississippi, which was charged with the defense of Confederate territory stretching from the Mississippi River to Kentucky and the Allegheny Mountains. To do this, he was allotted no more than twenty thousand troops, about half of whom lacked weapons, save for whatever rifles and shotguns they might themselves own. As one of his aides put it, Johnston “had no army.” After pressing President Davis for support, he received reinforcements led by Braxton Bragg, but the total number of troops available to Johnston never exceeded fifty thousand. When he asked for more, Davis instructed an aide to reply that nothing could be done for him and that he had to “rely on his own resources.”

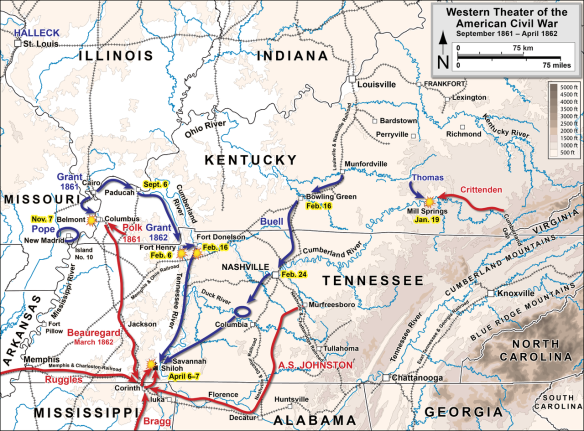

As if a shortage of manpower and equipment were not a sufficient handicap to performing what was, in fact, a hopeless mission, Johnston was instructed not to openly violate Kentucky’s avowed neutrality. This meant that all-important river defenses had to be placed within Tennessee, so that the two key forts, Henry (on the Tennessee River) and Donelson (on the Cumberland) were far from ideally sited. Vulnerable, the forts were lost in February 1862—Fort Henry on the 6th and Fort Donelson on the 16th. Although Johnston had had little choice about placement of the forts and was also compelled to build them hastily, he was showered with blame for their fall and for the consequences of their fall—the withdrawal of Confederate forces from Kentucky and middle Tennessee, and the loss of Nashville to Union occupation on February 25.

To demands from the press and some politicians that he fire Johnston, Jefferson Davis replied, “If he is not a general, we had better give up the war, for we have no generals.” For his part, Johnston accepted the blame for the reversals in the West, writing to the president that the “test of merit in my profession with the people is success. It is a hard rule, but I think it is right.”

Shiloh Campaign (1862)

BATTLE OF SHILOH, APRIL 6–7, 1862

Johnston accepted blame for the fall of the river forts, but he refused to concede that his theater had been lost. His plan was to rapidly consolidate as much of his forces from around the theater as he possibly could, to accomplish this before the enemy could consolidate his own, and to make a surprise attack on whatever portion of the Union forces presented itself as vulnerable. At this point he was joined by P. G. T. Beauregard, with whom he concentrated his forces at Corinth, Mississippi. Ascertaining that Grant was camped at Pittsburg Landing on the west bank of the Tennessee River near a place called Shiloh, Johnston resolved to mount a massive surprise attack before Grant’s Army of the Tennessee could be joined by Don Carlos Buell’s Army of the Ohio.

It was a bold, even brilliant idea, and its prospects for success were multiplied by Grant’s unsuspecting assumption that Johnston’s forces were in no shape to launch an offensive. If the very idea of the attack at Shiloh vindicates Jefferson Davis’s lofty appraisal of Johnston, the manner in which Johnston executed it reveals his greatest flaw as a commander. It was a failing he shared with no less a figure than Robert E. Lee. Like Lee, Johnston saw his role as strategic, and he accordingly left the tactical execution of his strategy to his subordinates. Like Lee, he avoided issuing direct, detailed orders and instead drew up a strategic outline. He relied on Beauregard to fill in the operational details and make it work.

Beauregard, it turned out, was not up to the assignment.

Ordered to advance on April 2, Beauregard should have executed a swift and stealthy movement that would ensure the preservation of surprise. Instead, lack of detailed planning and follow-through supervision resulted in lines of march that crossed and recrossed one another, creating a snarl of confusion and delay. The attack was supposed to be made on April 4, but the army was not in position until April 5. Both of Johnston’s subordinates, Beauregard and Braxton Bragg, advised their commanding officer to call off the operation. They were convinced that the snags, the noise, the delays had surely been more than enough to alert the Union forces in the area to the army’s presence. Although they calculated that the opposing forces were evenly matched at about fifty thousand men each (Grant actually fielded about forty-two thousand), Beauregard and Bragg assumed that Grant, expecting the attack, had entrenched his forces “to their eyes,” making for an impregnable objective. Moreover, undisciplined troops had consumed five days’ rations in just three. They were hungry and probably in no condition to give their best.

Johnston listened, hearing his generals out, then calmly replied: “I would fight them if they were a million.”

It was not bravado or arbitrary obstinacy that motivated the remark, but a cool, calculated military assessment. This attack, Johnston had concluded, no matter how risky, was the only opportunity he had to save the army and hold on to the Western Department theater.

The attack on Shiloh, April 6, 1862, began with breathtaking success. Grant had taken no defensive precautions whatsoever, and his encampment was soon overrun. Johnston, who had left the detailed planning and execution to Beauregard in the run-up to battle, now appeared everywhere on the battlefield, personally rallying, forming up, and leading troops.

By midday, victory seemed clearly within grasp. That is when Johnston’s troops encountered a pocket of intense, unyielding Union resistance they dubbed the “Hornets’ Nest.” In the initial attack, the Union soldiers had seemed to melt away. Now, at the Hornets’ Nest, wave after Confederate wave broke and fell. Seeing his troops retreat from this redoubt, Johnston dispatched an aide to General John C. Breckin-ridge to re-form his men and get them to return to the attack. Breckinridge personally rode back to Johnston to tell him that, try as he might, he could not get one of his regiments forward.

“Then I will help you,” Johnston quietly replied.

In company with Breckinridge, he rode up to the reluctant regiment and cantered along the line. As he rode slowly by—oblivious to the fire around him—he touched each soldier’s bayonet, as if to anoint their blades. “These,” he said in a voice just loud enough to be heard, “will do the work. . . . Men, they are stubborn; we must use the bayonet.” Reaching the end of the line, he turned in his saddle. “I will lead you,” he said.

And so they all swept forward, fired up, pressing forward behind their general—who, suddenly, reeled in his saddle.

Johnston’s aide, Isham G. Harris, galloped up, catching the general’s shoulder to keep him from falling. Are you wounded? he asked.

“Yes, and I fear seriously.”

Harris and others nearby lowered Albert Sidney Johnston from his horse. Harris frantically felt of his commander, searching for a wound, but he could find none. And yet the general slipped rapidly away. Only after he had died was it discovered that a bullet had entered behind his right knee, severing his popliteal artery. He bled out rapidly into his high cavalry boot, which concealed the wound and the volume of blood it produced. More than likely, given the location of the wound and his position when it was sustained, Johnston had been the victim of friendly fire.

P. G. T. Beauregard was so confident at the end of the day on April 6, 1862, that he reported to Richmond a great victory that had come, tragically, at the loss of the commanding general. In fact, without Johnston to lead, the battle was lost the following day. At the time of his death, Davis considered Albert Sidney Johnston the best general he had. Even after the emergence of Robert E. Lee some two months later in the war, Davis continued to rate Johnston as indispensable. He would attribute the collapse of the Confederate West to his loss.