Jefferson Davis judged him the Confederacy’s greatest general before the emergence of Robert E. Lee. Ulysses S. Grant believed him overrated. Through the years, Johnston’s reputation has seesawed, so that it is at least safe to say he is the single most controversial major Confederate commander to emerge from the Civil War.

Much of the controversy can be attributed to the unfinished nature of his career. He died in the middle of his one great battle, but that he died attempting what others would have considered impossible, mounting a bold offensive amid the collapse of an entire theater of war, hints at greatness. On the other hand, his willingness to entrust the execution of his bold and daring plans to others suggests a fatally flawed style of command.

The three saddest words in the English language, it is often said, are “might have been.” As with all momentous events of great consequence, the Civil War is filled with might-have-beens, especially with regard to the outcome of the war for the South. Two Confederate commanders have long endured as subjects of intense might-have-been speculation: Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson and Albert Sidney Johnston.

Some years after the war, Robert E. Lee himself reportedly voiced his belief that if he “had had Jackson at Gettysburg,” he would “have won the battle, and a complete victory there would have resulted in the establishment of Southern independence.” Jefferson Davis was even more emphatic about what the loss of A. S. Johnston meant. “It was,” he said, “the turning point of our fate; for we had no other hand to take up his work in the West.”

Yet there is a very important difference between Jackson and Johnston. When he fell at Chancellorsville, Stonewall Jackson had proven the potency of his genius, while Johnston, struggling to cover the vast Western Theater with an undermanned, under-equipped army, had just begun to reveal his powers. Davis, as well as many who served under Johnston, were convinced of his sovereign value to the cause, but Ulysses S. Grant, whom Johnston targeted for destruction at Shiloh, wrote in his Personal Memoirs of 1885: “I do not question the personal courage of General Johnston, or his ability, but . . . as a general he was over-estimated.”

Concerning Albert Sidney Johnston at least three facts are beyond dispute. He was assigned a vast and critical mission: to hold for the South the Mississippi Valley and beyond. He died with this mission unfulfilled. And, after his death, his reputation became one of the great speculative controversies of the war.

FROM THE KENTUCKY FRONTIER TO WEST POINT

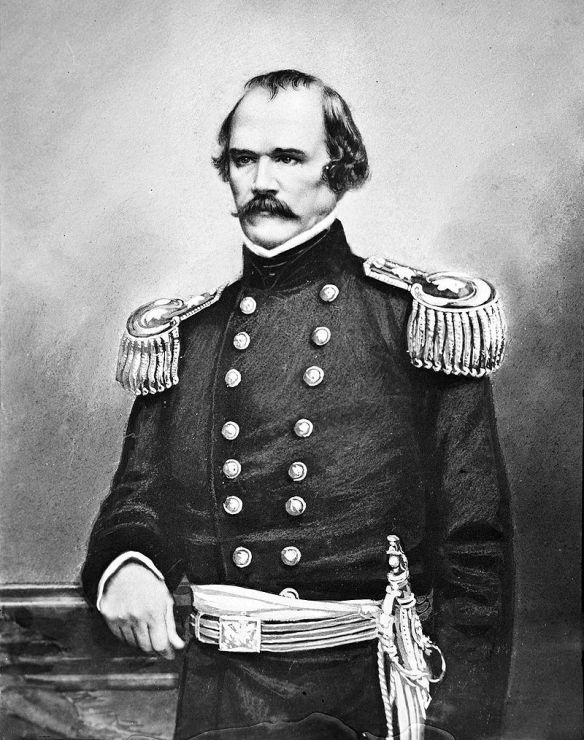

Albert Sidney Johnston was the son of Kentucky’s ragged frontier. When he was born on February 2, 1803, the Mason County village of Washington had yet to evolve into even a hardscrabble farming community. It was as yet a wilderness cluster of cabins huddling around a stockade fort raised to defend against the Shawnee and other hostiles determined to resist the incursion of white settlement. Men fed their families not with the produce of the earth, but with game on paw, wing, and hoof. It was a place that demanded wit, muscle, courage, will, and a talent for getting by on very little. This made it the ideal environment for breeding the leader of a hard-pressed army of rebellion.

Of course, Albert Sidney’s parents had no intention of raising a family of rebels. John Johnston was a skilled physician, whose own father had distinguished himself fighting in the American Revolution. The doctor was a New Englander by birth, hailing from Salisbury, Connecticut, and was among the many who saw in the West a way of twining his family’s future with the future of the nation. He quickly became prominent in Washington, Kentucky, developing a large practice and earning a seat on the local governing body, the board of trustees.

In this hard place, it proved beyond his medical ability to save his first wife, who succumbed to sickness in 1793. He remarried the following year, to another transplanted New Englander, Abigail Harris, who bore him four children before the birth of her last, Albert Sidney. But it was a hard place, and in the boy’s third year of life, his mother died.

Without a mother, it was his father and his oldest sister who raised him up, kept him safe, and saw to it that he received an education well above the frontier standard. While he attended private school through the college preparatory stage, he was also encouraged to indulge an intensely competitive love of riding and hunting, as well as athletic contests with local boys. He grew into a strapping young man of over six feet in height and was the object of admiration throughout the district. John Johnston sent him off to Transylvania College in Lexington, hoping that he would follow in his footsteps and become a physician. There he met fellow student Jefferson Davis, and there he also grew restless in the study of medicine and asked his father to help him obtain an appointment to West Point.

He enrolled in 1822 (Davis would follow two years later) and earned a reputation for satisfactory if not exceptional academic performance. Far more outstanding was his soldierly bearing, the warmth of the friendships he formed, and the sense he created among the other cadets that he was a natural and irresistible leader. He possessed, as if inborn, what soldiers call “command presence,” and while a few others overtook him academically (he would graduate eighth in the forty-one-cadet Class of 1826), it was he who was selected as adjutant in his fourth year, the highest honor a cadet can attain.

BLACK HAWK WAR, 1832

Even before he had entered West Point, Johnston excelled at mathematics, and this, coupled with his high class standing, should have propelled him into an assignment in the artillery, second only to the Corps of Engineers in attracting the top academy graduates. But he chose the infantry instead, believing this branch would give him wider scope as a tactician—another of his classroom passions—and, even more important, would offer greater opportunity for higher and more rapid advancement. So strong was this belief that he even turned down an invitation to join Winfield Scott’s personal staff.

Having made his decision, he was commissioned a brevet second lieutenant in the 2nd U.S. Infantry. To his chagrin, for the next eight years he did not budge from his initial commissioned rank. Such was the nature of the diminutive U.S. Army at peace.

Johnston served in New York for a time before being transferred to Jefferson Barracks at St. Louis, Missouri. He soon met Henrietta Preston, a Louisville belle and the daughter of William Preston, veteran of the American Revolution and prominent in Louisville society and politics; his son, also named William, would become a general in the Confederate forces. The couple married on January 20, 1829, which must have brought some relief to the monotony of garrison life, but it was not until the outbreak of the Black Hawk War in 1832 that a genuine career breakthrough seemed to be in the offing.

Assigned as chief of staff, aide-de-camp, and assistant adjutant general to Brevet Brigadier General Henry Atkinson, commander of a regiment sent to put down Black Hawk’s “uprising,” Johnston yearned for combat. As the general and the regiment prepared for transportation by steamboat up the Mississippi, the young staff officer gained valuable hands-on experience in support and logistics. The trip itself, however, was uneventful, and neither Johnston nor the rest of the regiment would participate in active combat. They arrived at the confluence of the Bad Axe and Mississippi Rivers in time to observe elements of the U.S. Army and local militia massacre members of Black Hawk’s “British Band” who sought nothing more than to surrender. For Johnston, it was a disheartening, disturbing, and depressing maiden battle.

TEXAS REPUBLIC, 1836–1840

Discouraged with army life, deeply in debt, seeing no realistic hope for promotion, and learning that his wife had fallen ill with consumption, Johnston resigned his commission in 1834 to return to Kentucky and look after her. It proved to be a prolonged death watch. Henrietta Preston succumbed to her disease in 1836. Their son, William Preston Johnston, would come of age in time to serve as a colonel in the Confederate Army.

To the widower, debt ridden and devoid of prospects, life looked bleak. He sought escape in revolutionary Texas, enlisting later in the year as a private in the Texas army. The Texas Revolution had been won with Santa Anna’s defeat at the Battle of San Jacinto on April 21, 1836, but the Mexican government repudiated the treaty signed under duress and made noises about its intention to reconquer the Lone Star Republic. Within a month of his arrival in Texas, Johnston was embraced by President Sam Houston, who jumped him in rank from private to major and appointed him his personal aide-de-camp. On August 5, 1836, he was promoted to colonel and named adjutant general of the Republic of Texas Army, and on January 31, 1837, Houston named him the army’s senior brigadier general, with overall command of the entire force.

The promotion vaulted Johnston over Brigadier General Felix Huston, who accused him of attempting to “ruin his reputation” by accepting the appointment. Honor and duty were uppermost in Johnston’s hierarchy of values, but he did not believe in fighting duels to defend the former, yet, in this case, he believed that the latter—duty—dictated that he accept the challenge. Failing to do so, he feared, would sacrifice credibility with his troops and, with it, his authority to command. The two men met with pistols on the “field of honor” at dawn on February 7, 1837. Accounts vary as to precisely what happened. According to some, Johnston refused to fire on Huston, who, having no such scruples himself, aimed, shot, and hit Johnston in the right hip. Others insist that both men fired repeatedly, exchanging as many as four shots without any finding its mark. On the fifth shot, Johnston was hit in the right hip (some accounts describe it as the pelvis), the round apparently passing through and through without striking bone. It is unclear whether Johnston recovered sufficiently and in time to assume active command as senior brigadier general, but on December 22, 1838, the second president of the Republic of Texas, Mirabeau B. Lamar, appointed him secretary of war.

The appointment thrilled Johnston. It looked certain that Mexico was about to make good on its threat to invade Texas with the object of reclaiming it, and some five thousand Mexican troops had assembled on the border at Matamoros and Saltillo. After leading a campaign against hostile Indians in northern Texas in 1839, Johnston organized the border defenses. But early in 1840, the Mexican government recalled its troops from the border, and President Lamar indicated his unwillingness to further press any Texas grievance against Mexico. Frustrated, bored, and seeing as little opportunity in the Texas army as he had had in the U.S. Army, Johnston resigned as secretary of war in February 1840 and was back in Kentucky by May.

U.S.-MEXICAN WAR, 1846–1848

Johnston had managed to put together a small amount of money during his time in Texas, which he now used to finance a Kentucky land speculation scheme. It quickly blew up in his face, and, once again, he found himself heavily burdened by debt. His cares were somewhat relieved by a budding romance with Eliza Griffin, the twenty-three-year-old cousin of his late wife, “a dazzling beauty of the Spanish type,” according to a friend of Johnston’s, and an accomplished singer and painter. They married in October 1843.

The couple struggled, living mostly on Eliza’s funds, with Johnston growing increasingly desperate until, once again, war offered a way out. When Mexican forces attacked Zachary Taylor’s army on the Texas border in April 1846, Johnston’s first thought was to renew his commission in the Army of the Republic of Texas. Discovering that it had been voided with the annexation of Texas to the United States, he sought a new commission in the regular U.S. Army. Unable to obtain this, he secured a commission as colonel of the 1st Texas Rifle Volunteers, which were subsequently attached to Taylor’s forces.

He assumed command in time to see action in the Battle of Monterrey (September 21–24, 1846), but the six-month enlistments of his short-term volunteers were set to expire just before then. Although he persuaded a handful of his men to remain and fight under him, he was essentially a colonel without a command. At the last minute, he wrangled an appointment as inspector general of volunteers and, in this capacity, saw action at Monterrey and at Buena Vista (February 22–23, 1847). At Monterrey, he distinguished himself in spectacular fashion. Without a command of his own, save for the handful of volunteers who had chosen to fight by his side, Johnston was free to employ himself on the field wherever he saw fit. Noting that an Ohio regiment was in danger of being routed by Mexican lancers, Johnston rallied many of the retreating men, who had taken refuge in a corn-field. Re-forming them into an effective line of fire, he personally led a counterattack against the pursuing lancers, driving them back. Joseph Hooker, a captain in the war with Mexico and destined to be a Union general, gave Johnston credit for saving “our division . . . from a cruel slaughter. . . . The coolness and magnificent presence . . . displayed . . . left an impression on my mind that I have never forgotten.” Jefferson Davis, commanding the Mississippi Rifles at Monterrey, praised Johnston’s “quick perception and decision” and called them the characteristics of “military genius.”