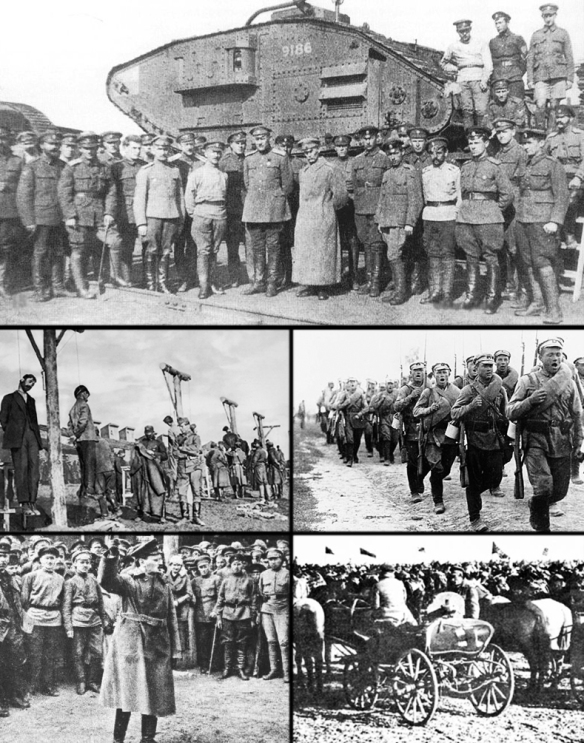

Clockwise from top: Soldiers of the Don Army in 1919; a White infantry division in March 1920; soldiers of the 1st Cavalry Army; Leon Trotsky in 1918; hanging of workers in Yekaterinoslav by the Austro-Hungarian Army, April 1918.

In the West today, Siberia is remembered as a land of living death where post-Revolutionary Russian governments confined millions of ‘counter-revolutionary elements’, common law criminals and dissidents in the Gulag camps. Before the Trans-Siberian mainline was constructed in the nineteenth century to connect St Petersburg on the Gulf of Finland with the Pacific at Vladivostok – the name means ‘lord of the East’, implying Russian ownership of the East Asian littoral – long columns of convicts were marched into Siberia, many of them in chains. They stopped at the border for men and women both to kiss the earth of Mother Russia and wrap a handful of it in a piece of cloth or paper, to treasure during their exile. Few of them felt anything for Siberia except that it was immensely vast and about as hospitable as the far side of the moon; even fewer expected to return.

Its enormous climatic differences over a north–south extent of 2,000 miles include one of the coldest inhabited places on the planet: recorded temperatures at Verkhoyansk range from a low of minus 69°C in mid-winter, when there is no daylight for two whole months, to a midsummer high of 37°C. The construction of the Trans-Siberian railway, which cost thousands of lives and was largely financed by foreign loans that were never repaid, was for two reasons: to open up the territory’s rich mineral and other resources to commercial exploitation with slave labour; and to move troops quickly from European Russia to the Pacific littoral, a train journey of 5,000-plus miles. It was indeed the perceived threat to Japan posed by the second purpose of the railway that triggered the 1904–5 Russo-Japanese war which ended so disastrously for Russia, the enormous number of casualties being a major cause of the 1905 revolution.

How many diners in a Chinese restaurant realise that the Tsingtao beer which washes down their dim sum is made from a recipe first brewed at the Germania brewery established in Tsingtao (modern Quangdao) after the German annexation of the port in 1898? What had originally been a poor Chinese fishing village became the home port of the Kaiserliche Marine’s Ostasiatische Kreuzergeschwader or Far Eastern Squadron. On 7 November 1914 a joint British and Japanese force captured the port from the German navy, making passage to Vladivostok safe for supply ships that transported millions of tons of materiel, to be dumped there for forwarding along the Trans-Siberian to the tsarist forces fighting 5,000 miles to the west. Some supplies, including Japanese rifles and ammunition, were transported, but despite the French and British governments urging their Japanese allies to take responsibility for security in eastern Siberia, where geography favoured them, Tokyo was playing a different game, in which the real prize was the hoped-for seizure of Manchuria and a large slice of north-eastern China.

By December 1917 no less than 600,000 tons of undistributed supplies had accumulated at Vladivostok, although the Bolsheviks had taken command of the harbour area and were sending shipments to the Red forces. To discourage them, the Admiralty tried the technique that had worked so well against ‘the lesser breeds without the law’ through the nineteenth century, and sent a gunboat: the British Monmouth Class cruiser HMS Suffolk was despatched from Hong Kong. In a game of nautical chess, Tokyo moved two rather ancient battleships – Asahi and Iwami – to outbid the single cruiser flying the White Ensign in Vladivostok harbour, but Japanese ground forces made no move, even when it was again suggested that they would fulfil a useful function by taking over security of the Trans-Siberian.

The railway still functioned, after a fashion. Florence Farmborough had been given permission in Moscow to travel with a group of other foreigners on the longer, northern route to Vladivostok for repatriation. After leaving behind the Urals in March 1918 in the dirt and discomfort of what was termed ‘a fourth-class carriage’ attached to a freight train, their journey was described as ‘twenty-seven days of hunger and fear’. From Perm to Ekaterinburg and on to Chelyabinsk they progressed slowly, their train making only 10 or 12 miles on some days after being repeatedly shunted into sidings as more important traffic thundered past. At Omsk, Red Guards stormed the foreigners’ carriage, pushed aside the screen of male passengers and insisted on searching every compartment in the hope of finding fleeing tsarist officers to execute by firing squad. Finding women and children instead, they ignored the protests, the properly authorised Soviet travel papers and the British passports to search the baggage for arms or contraband. From Omsk, the train slowly continued to Irkutsk and skirted svyatoe morye – the holy sea of Lake Baikal – on the last stretch of the line to be completed, which had required forty tunnels to be blasted and hacked through mountains that came right down to the water.

The people in the virgin forests and tundra of Transbaikalia were Asiatics: Kalmuk and Buryat. Soon Chinese faces became more common. After Chita, the Manchurian border being closed, the train followed the mighty Amur River, where mutinying troops had killed the governor, but allowed his two teenage daughters to walk away. One of them, called Anna Nikolaevna, later taught the author at the Joint Services School for Linguists in Crail. That she was somewhat odd is understandable after living through that and having to beg her way with her sister on foot for 600 miles from Blagoveshchensk to Vladivostok, where they hoped to find a ship to take them to Europe. On the way, they soon learned that poor peasants would normally share food with them while richer people turned them away.

At least Florence Farmborough did not have to walk. After arrival at Vladivostok, the passengers on her train were immensely cheered to see His Majesty’s ships Suffolk and Kent moored in the harbour. British, American, French, Belgian, Italian and Japanese soldiers patrolled the streets, thronged with thousands of civilian refugees of many nationalities. Whilst Red Guards were still a nuisance, their worst excesses were restrained by the Allied presence. She was told this was because a White general named Semyonov – but who behaved more like the Baikal Cossack ataman or warlord that he also was – was expected shortly to drive the Bolsheviks out of the port-city altogether. At night none of the passengers left the train, which was parked in a coal siding, because shots were frequently heard. The greatest joy for the weary, and very hungry, travellers was to find that food could freely be purchased in the Chinese street market, at a price. Spirits fell somewhat when a Chinese ship sailed into harbour flying a yellow fever flag and they learned that there was an epidemic of typhoid and smallpox among the undernourished coolies working as dockers.

After three weeks in the coal siding, guarded at night by a shore patrol from HMS Suffolk, great was their excitement at the arrival of a passenger ship to take them to San Francisco. Embarking themselves and their luggage under the protection of American sailors who beat off any interference from the locals and from other refugees who did not have the right papers, Florence and her exhausted companions settled into their overcrowded cabins, revelling in clean bed linen, clean towels and even clean curtains at the portholes. They went on deck to be played out of harbour by Royal Navy, US Navy and Japanese bands on the decks of the ships moored there.

Among the passengers on board was the indomitable Maria Bochkaryova, who had narrowly escaped execution by Red Guards on two occasions since being invalided back from the front. Early in 1918 she had been asked by loyalists in Petrograd to take a message to White Army commander General Lavr Kornilov. After fulfilling that mission, she was again detained by the Bolsheviks and sentenced to be executed until a soldier who had served with her in 1915 convinced his comrades to stay her execution. Thanks to him, she was granted an external passport instead, allowing her to leave for Vladivostok, en route to the USA. There, she dictated her memoirs to an émigré Russian journalist and met President Woodrow Wilson – and later King George V in London – to plead for Western intervention forces to crush the Bolsheviks.

Although she could certainly have requested political asylum in the West, she begged the War Office to let her return to Russia and continue the fight. In August 1918 she landed in Archangel, where she attempted to form another women’s combat unit without success. In April of the following year, she returned to her home town of Tomsk, hoping to recruit a women’s medical unit to serve under Admiral Kolchak. Captured by Bolsheviks, she was interrogated in Krasnoyarsk and sentenced again to death as vrag naroda – an enemy of the people. Sentence was carried out by firing squad on 16 May 1920. So ended the life of one of the bravest people to fight on the Russian fronts.

It has to be admitted that both sides in the civil war committed atrocities. The Whites justified this by regarding the enemy as traitors to Russia. The Reds regarded them as traitors to the Revolution. General Semyonov had one of the worst records, frequently holding hostages for ransom and holding up trains belonging to both sides like a bandit. However, he had his uses, so the British decided in February 1918 to pay him £10,000 a month. Two months later, the subsidy was cancelled, since his ‘army’ was more interested in looting than fighting. With smaller handouts from the French, he stayed in the region. To stop the large-scale pilfering of stores from the widely separated dumps of Allied stores, the captain of Suffolk proposed landing Allied ground forces, meanwhile deploying fifty Royal Marines in a cordon around the British Consulate. The Japanese took off the velvet gloves and landed 500 troops to restore order, but by 25 April these troops were withdrawn and the Bolsheviks were again masters of the port, the city and the stores.

A Belgian armoured car corps arrived – sans armoured cars or guns, which they had sabotaged after being given permission to withdraw via Vladivostok. Next came some of the Czech Legion, now several thousand men strong – and all impatient to get out of Russia and participate in the liberation of their homeland. The war on the Western Front was, of course, still ongoing at this point. Suffering some casualties, they kicked the Bolsheviks out of Vladivostok after just fifty-eight days of skirmishes and demanded stores from the Allied dumps so they could travel back along the railway to rescue the large number of their comrades far in the rear, who had taken control of the major Siberian city of Irkutsk after fighting with the Bolsheviks there. These were men who, forcibly conscripted by the Central Powers, had been taken prisoner and then volunteered to go back into action until Trotsky signed the second Treaty of Brest-Litovsk. It says something about their esprit de corps that the slogan painted on the cattle wagons in which they lived on the railway was ‘Each of us is a brick, together we are a rock’.