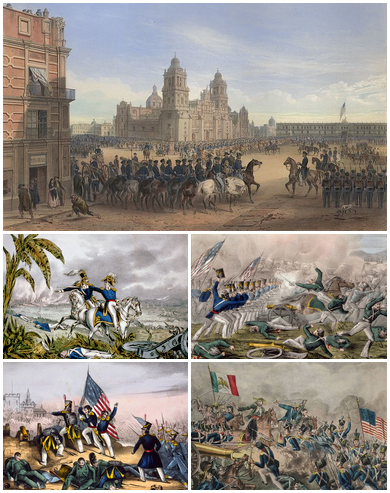

Clockwise from top left: Winfield Scott entering Plaza de la Constitución after the Fall of Mexico City, U.S. soldiers engaging the retreating Mexican force during the Battle of Resaca de la Palma, American victory at Churubusco outside Mexico City, U.S. marines storming Chapultepec castle under a large American flag, Battle of Cerro Gordo

The United States had conquered California once before. In 1842, American Navy Commodore Thomas Ap Catesby Jones sailed to Monterey and demanded surrender from the Mexican governor. He did so under the mistaken impression that Mexico and the United States were imminently to be at war. When he was assured this was not the case, he returned the Mexican governor to the seat of power and sailed away.

This interesting precedent did not do much to encourage pro-American feeling in the Mexican government, and the Mexicans spurned President Polk’s attempts to buy California. But it would appear that affronted pride rather than practicality guided Mexican policy, for if Commodore Jones could sail into Monterey once, he could do it again. California was sparsely populated with Mexicans and pacific Indians. More important, it already had a few American settlers—and Mexico should have known what that meant.

Polk certainly did. In 1845, he was encouraging the Americans in California to emulate their cousins in Texas and shake the sleepy territory with calls for liberty and annexation by the United States. Urgency was required not so much because of any aspect of Mexican policy, but because Polk feared the intentions of Britain—the Royal Navy appraisingly eyed the California coastline—and the Russian bear, who had established trading posts in California.

Meanwhile, Polk moved Zachary Taylor and the United States Army to protect Texas’s southwestern border with Mexico. Mexico had broken off diplomatic relations with the United States because of the annexation of Texas. Polk sent John Slidell to Mexico anyway demanding that Mexico pay off its debts (from bonds and other obligations) owed to the United States. But, of course, Slidell—rather the perfect name for a diplomat—had a deal. The debts could be cancelled if Mexico would affirm the Rio Grande as the Texas-Mexico border. In addition, if Mexico ceded the territories of New Mexico and California to the United States, the American government was willing to pay five million dollars for the former and many more millions of dollars—Mexico could set the price—for the latter.

The Mexican president José Joaquin de Herrera huffily refused to see Slidell, but was swiftly overthrown by General Mariano Paredes. General Paredes was adamant: any more yanqui talk about debts and purchases and annexations meant war. Polk’s response was: don’t mind if I do. He ordered Zachary Taylor across the Mexican-established Texas border (along the Nueces River) to a position 150 miles south along the Rio Grande (the border claimed by Texas). Taylor trained his guns on Matamoras, Mexico, which he blockaded. The American challenge was clear: come and get me. The Mexican army took the bait, ambushing a detachment of American dragoons, killing eleven of them. Polk now had the casus belli he wanted. The president, who noted in his diary that he regretted disturbing his Sabbath reflections working out the proper response, announced that Mexico had precipitated a war against the United States. This was truer than Polk knew, because the war was already under way. Neither the Mexican army nor Zachary Taylor waited for official word from Washington. President Polk requested a congressional declaration of war on 11 May 1846—after two major battles: Palo Alto (8 May) and Resaca de la Palma (9 May).

Much of America—especially the North—was skeptical. Polk, they thought, had manufactured an unnecessary war; it was an act of aggression to add more slave states to the Union. A young congressman from Illinois named Abraham Lincoln was one of the doubters. In the event, congressional authorization for the war passed overwhelmingly in both houses. But it was the southern states closest to Texas that were full of enthusiasts and volunteers. They remembered the heroism of the Alamo, the outrage at Goliad, and the victory at San Jacinto. They brought down their muskets, kissed their sweethearts good-bye (or, if more rustic, packed up a big supply of chewing tobaccy), and mustered themselves into militias or volunteer units. Equally enthusiastic were the generals of the Mexican army, who hankered to repel Zachary Taylor, regain Texas, and even attack Louisiana.

The Mexican army numbered more than 30,000 men, while the American regular army was less than one-fourth that size. But what the Americans lacked in numbers, they made up for in the quality of their units and in the tens of thousands of volunteers who already knew how to handle a gun and weren’t afraid of nothin’—neither Indians, nor bears, nor Mexicans—and in fact rather enjoyed the idea of fighting and conquering for the United States. Lieutenant Ulysses S. Grant—who would become no small judge of soldiers—wrote home proudly that “a better army, man for man,” than Zachary Taylor’s 2,300 men, “probably never faced an enemy.”

The Mexican army, on the other hand, though impressive in numbers, was ill-trained (for one thing, the soldiers nervously fired from the hip) and top-heavy. It had more officers than enlisted men, and its officers stood on their authority while their peon-class troops stood only until it became obvious that survival recommended fleeing in another direction. The best soldiers in the Mexican army were a special class of mercenaries the Mexicans acquired just before and during the hostilities: American deserters, specifically, Catholics—many of them Irishmen, who made up a quarter of the American enlisted ranks—who chafed under the harsh discipline of their commanders and felt drawn to their coreligionists (the Irish Catholic soldiers had no chaplains of their own in the U.S. Army). The Catholic deserters—whom the Mexicans actively recruited with claims that the United States acted as a Protestant power seeking to exterminate the Catholic Church in Mexico—formed the Batallón de San Patricio (Saint Patrick Battalion) under the command of an Irish-born private named John O’Reilly. The fighting Irish, like the tenacious Scotch, are natural-born soldiers; and so it proved here.

Meanwhile, Old Rough and Ready Zachary Taylor lived up to his name by playing rough and ready with martial law, executing a couple of foreign-born rankers (a Frenchman and a Swiss), before the official onset of hostilities, in order to discourage further desertions. In those days, admirable men like Andrew Jackson and Zachary Taylor treated “legality” with the proper respect it deserved: damn little. Practicality before pettifoggery is the law of reasonable men.

Such practicality also induced President Polk to refute the Mexican charge that the United States was fighting a religious war. The president asked American Catholic bishops for help, and two priests were dispatched to provide the sacraments for Catholic soldiers. The priests were officially civilians—there were no chaplain billets open to them—but they shared the hardships of the men. Mexican bandits murdered one of the priests and the other eventually fell prey to sickness and had to be sent home. From Washington, Zachary Taylor received a proclamation to be delivered to the Mexican people: “Your religion, your altars, and churches, the property of your churches and citizens, the emblems of your faith and its ministers shall be protected and remain inviolate…. Hundreds of our army, and hundreds of thousands of our people are members of the Catholic Church….” Whether this did much good is open to question. Mexican priests bemoaned the fact that the barbarian American volunteers were “Vandals vomited from Hell.” The American regular officers who had to deal with these violent, recalcitrant, and unwieldy Kentuckian, Tennessean, and Texan frontiersmen—about whom they themselves complained—no doubt sympathized. But focused on their task, the “Vandals vomited from Hell” made excellent soldiers.

The first major engagement was the Battle of Palo Alto (8 May 1846), where Mexican General Mariano Arista, having crossed the Rio Grande and failed to take Fort Texas, drew up his artillery, lancers, and infantry to confront Zachary Taylor’s army. In the ensuing artillery duel the American gunners—with the accuracy that was their trademark—got much the better of the Mexicans, and General Arista withdrew his men. At that night’s council of war Zachary Taylor seconded the opinion of Captain James Duncan: “We whipped ’em today and we can whip ’em tomorrow.” So the Americans pursued General Arista’s army and whipped ’em again, despite the Mexicans having well-laid battle lines at Resaca de la Palma and despite the Mexicans outnumbering the Americans by 4,000 men. The Americans whipped the Mexicans all the way back across the Rio Grande. In their flight, the Mexicans left their border town of Matamoros undefended.

In Old California things went even better. The American settlers declared their independence, and the California Bear Flag Republic was born. There was no California Alamo because when the California rowdies knocked on the door of California’s Commandante-General Mariano G. Vallejo and arrested him, they discovered he was actually on their side: he favored American annexation. California’s status as a great independent republic, a historical memory some of us still honor, lasted all of twenty-four days before Commodore John Sloat repeated Commodore Thomas Ap Catesby Jones’s deft, if premature, capture of California by sailing into Monterey on 9 July 1846 and declaring that California was hereby annexed to the United States.

To the east, Colonel Stephen Kearny marched from Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, to New Mexico and took the territory without firing a shot, entering Albuquerque on 18 August 1846. Like the Californians, the New Mexicans welcomed annexation. When Kearny received news of action in California, he decided to rush his troopers across the desert to help the American cause.

He left a detachment of men in Santa Fe to take care of a few troublemaking Indians and Mexicans. He sent another unit south to assist in the invasion of central Mexico and link up with Zachary Taylor’s army. Kearny himself took a party of dragoons and, using Kit Carson as his scout, raced across the sands of Arizona and California. His men, hungry and haggard, were met not by California senoritas bearing margaritas (which, alas, had not been invented yet) but by Californio lancers at San Pasqual about forty miles northeast of San Diego. The lancers bloodied Kearny’s men in an engagement on 6 December 1846. Three officers were killed, and Kearny himself was among the wounded. But the Americans kept the field through the strength of their artillery. Kearny then withdrew his men to San Diego where the American Navy was already established. In league with Commodore Robert Stockton, Kearny rested, refitted, and reinforced his troops and marched them north, besting the Californios in two consecutive engagements—the Battle of the San Gabriel River (8 January 1847) and the Battle of La Mesa (9 January 1847). That was enough. California was won.

In Texas, fighting continued, and with equal ease Zachary Taylor’s men took Matamoros in May and Camargo in July 1846. And there, in what proved to be a pestilential location—full of scorpions, tarantulas, and disease that claimed the lives of one of every eight encamped soldiers, including a disproportionate number of volunteers—Taylor prepared his army for what would be its first testing encounter, at Monterrey.

The city’s geography, on high ground backed by the Santa Catarina River to the south, made it easily defended. The city itself was built like a fortress. The streets were blockaded. And the stone houses of the city were mini-blockhouses. A thousand yards north of the city was the Citadel, a real fortress that the Americans called the “Black Fort” for its dominating position on the field and the danger it posed to any American attack. In addition, the Mexicans had built two new forts—Fort Tenería and Fort Diablo—to defend the city’s eastern flank. To the west, the two hills that straddled the Saltillo Road leading into the city were well defended. Indepedencia Hill had Fort Libertad with 50 men and a couple of guns as well as the fortified ruins of a bishop’s palace held by another 200 men and four guns. On Federación Hill was Fort Soldado on its eastern side and a small gun emplacement on its western side. The Mexicans had more than 7,000 regular soldiers and forty-two guns at Monterrey. Against them, Taylor had 6,000 men.

Zachary Taylor faced a daunting military task, but he quickly discerned the hidden weakness of the Mexican position. Fort Tenería, Fort Diablo, the Citadel, the hill forts, and the city itself were so positioned that each could be isolated and unable to support the other. Unless the Mexicans massed to meet him on open ground, the fortifications could be tackled individually. Taylor, a strong believer in directly storming positions with bayonets—it worked against Seminoles, after all—authorized a more creative, if potentially dangerous, plan at Monterrey. He divided his troops for separate simultaneous assaults. The advantage lay in bypassing the Citadel. General William Worth’s division would strike the hill forts to the west while the rest of the army hit the newly constructed forts in the east and break into the city. The danger lay in dividing his forces and in trying to coordinate the assaults.

On the morning of 21 September 1846, the attack began. Worth’s men advanced on the Saltillo Road, hurling back charging Mexican cavalry and inflicting heavy Mexican losses. By nightfall they had seized—and were celebrating the capture of—Federación Hill. Zachary Taylor, meanwhile, tried to keep the defenders of the Citadel pinned down with artillery fire, while he gave Lieutenant Colonel John Garland ambiguous orders about striking from the east. Taylor had meant Garland’s to be a diversionary attack. Garland took it to be the lead of the main attack, and quickly got into trouble. His men got stuck in the sweet spot for the Mexican defenders where he was open to fire from the Citadel, the two eastern forts, and the city. More American units charged in to support him. Mexican fire stubbornly cut them down, but when the Americans didn’t withdraw, the Mexicans panicked. The commander at Fort Tenería and half his men ran away.

Colonel Jefferson Davis of the Mississippi Rifles saw his moment: “Now is the time! Great God! If I had 30 men with knives I could take the fort!” Even without those men, he and the other charging volunteers took it. But the reduction of Fort Tenería had taken until noon, and though artilleryman Braxton Bragg had managed to bring artillery up to the very streets of Monterrey, the rest of the day was a stalemate. Four hundred Americans, a quarter of them Tennesseans, were dead or wounded: a high price to pay for the capture of a single supporting fort.

On 22 September, Worth again took the lead, spending the day clearing the defenders from Independencia Hill—a job made easier by the Mexicans in the bishop’s palace choosing to charge the Americans rather than sit tight behind their defenses. On the other side of Monterrey, the Americans were disinclined to do anything but reorganize themselves for another try the next day. This was just as well, as the Mexican commander, General Pedro de Ampudia, abandoned Fort Diablo and his other outlying positions and concentrated his defenders in the city and at the Citadel.

The third day of battle did not look auspicious for the Americans. Worth’s men, though victors, had spent two nights in drenching rains, had scaled two hills, and had two full days of fighting—all without food. Their one great incentive to assault the city was to hit the larders. At the other end of Monterrey, the Americans began a reconnaissance in force that penetrated the city with minimal opposition. The Americans then cleared the defenders house by house, with tactics very similar to those that would be used today: breaking down doors (or walls), tossing in grenades, and then clearing the rooftops. From there, they provided covering fire for troops attacking the next house. Thus, the Americans methodically and efficiently advanced, with light artillery support, clearing blockaded streets. Worth never received orders, but at the sound of firing led his men into the battle and advanced house by house from the west.

The Americans did not press into the center plaza—where the civilians huddled in the cathedral, which General Ampudia was also using as an ammunition dump—but pulled back and dropped mortar rounds into it. As the shelling came closer to the cathedral, General Ampudia came closer to losing his nerve. Well before dawn, General Ampudia opened communications with Taylor that over the course of the next twenty-four hours led to the surrender of Monterrey. Taylor eventually conceded—under hard Mexican negotiating—extremely generous terms that allowed the Mexican army to evacuate the city with its arms and under cover of an eight-week armistice.

President Polk, when he learned of the terms, privately denounced Taylor for a lack of aggression. The Democrat Polk already suspected Taylor of Whiggish presidential ambitions—a military hero on a literal white horse (Old Whitey). Now he suspected him of being soft on Mexicans, too. It did not help that General Winfield Scott (a Whig) cheered Taylor’s “three glorious days,” which was how the battle appeared in the popular press. Taylor appointed Worth governor of Monterrey and set about using the armistice to patch up and rebuild his army.