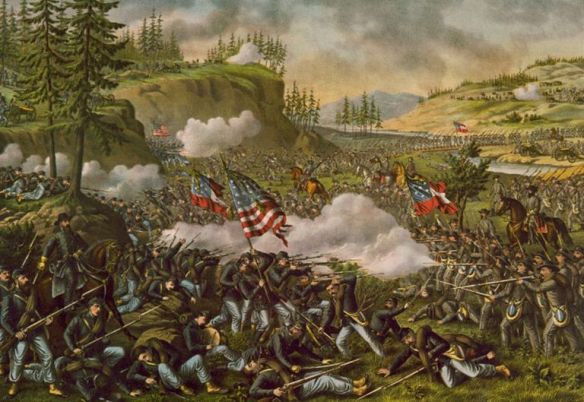

BATTLE OF STONES RIVER, DECEMBER 31, 1862–JANUARY 2, 1863

Having declined command of the Army of the Ohio when it had been offered him the first time, Thomas was angry at being passed over the second time. This fact said much about his character and sense of justice. Buell was his senior, and so he considered it wrong—disloyal and unseemly—to take a command away from him. By the same token, Rosecrans was his junior and therefore should not have been offered the command. A forthright man, Thomas brought this up with Rosecrans and requested a transfer. Rosecrans responded by asking for Thomas’s help. Put this way, Thomas found that he could not refuse. Rosecrans offered him a range of commands. Thomas chose to lead the center corps.

When Lincoln and Halleck pressed Rosecrans to attack Bragg at Murfreesboro, Tennessee, Thomas advised Rosecrans not to hurry. While Thomas was aggressive, he was also highly methodical and believed that careful preparation was an indispensable key to victory. As long as Rosecrans did not feel fully prepared to launch the offensive, Thomas advised resisting the pressure from Washington.

But if Rosecrans wasn’t ready for a fight, Bragg was. On December 31, 1862, he attacked Rosecrans’s right flank at Stones River, achieving total surprise as the Union soldiers were busy preparing breakfast. Union retreat was orderly, but relentless. At the end of the first day, Rosecrans met with his generals to decide whether to continue the fight tomorrow or withdraw now. When he asked Thomas, “General, what have you to say?” the reply was stark and calm: “Gentlemen, I know of no better place to die than right here.” The words put spine into Rosecrans, who dismissed his commanders with, “We must fight or die.”

And fight and die many did. On both sides, casualties were stunning. Of 43,400 Union troops engaged, 13,249 became casualties, killed, wounded, captured, or missing; on the Confederate side, the number was 10,266 out of 37,712: casualty rates of 30 and 27 percent respectively—the highest of any major engagement in the war. In the end, it was Bragg who retired from the field, thereby putting the victory in the Union column, though nothing, really, was decided by the horrific battle.

BATTLE OF CHICKAMAUGA, SEPTEMBER 19–20, 1863

Because Rosecrans had achieved so little at the bloody Battle of Stones River, by the early spring of 1863, President Lincoln was making noises about relieving him. “Old Rosy” heard him and reluctantly bestirred himself to bottle up Bragg in Tennessee so as to prevent his troops from reinforcing Vicksburg, to which Grant was laying siege.

Rosecrans relied heavily on Thomas to lead a series of brilliant feints and deceptions, executed during seventeen miserable days of driving rain, which positioned his troops behind Bragg’s right flank near Tullahoma, Tennessee. On July 4, Bragg, outnumbered, withdrew from Tullahoma and fell back on Chattanooga, which is precisely where Rosecrans wanted him. However, without reinforcements, Rosecrans decided not to risk a frontal assault but instead recommenced maneuvering, with Thomas leading a stunning surprise crossing of the Tennessee River thirty miles west of Chattanooga and then marching through a series of gaps in Lookout Mountain, the long ridge south-southwest of Chattanooga, to sever the Western and Atlantic Railroad, Bragg’s supply and communications artery to Atlanta. By cutting this, Rosecrans and Thomas gave Bragg no choice other than to evacuate Chattanooga—which he did, without firing a shot.

Buoyed by his remarkable victory at Chattanooga, Rosecrans, so reluctant to start his campaign, now didn’t want to stop. Thomas counseled him to rest and consolidate his forces at Chattanooga before marching on. Instead, he kept going after Bragg, his three worn-out corps becoming separated from one another in the heavily forested mountain passes. In the meantime, Bragg halted at LaFayette, Georgia, twenty-five miles south of Chattanooga, where he took on substantial reinforcements. Thus fortified, Bragg positioned his men for a counterattack at Chickamauga Creek, Georgia, a dozen miles south of Chattanooga.

On September 18, the night before the battle, both commanders shifted and moved troops. In the dense woods, neither side knew the other’s position. Even worse, none of the commanders on either side was fully aware of the disposition of his own troops. With daybreak on September 19, Thomas ordered a reconnaissance near Lee and Gordon’s Mill, a local landmark on Chickamauga Creek. These troops, led by Brigadier General John Brannan, encountered and drove back the dismounted cavalry of Nathan Bedford Forrest. He, in turn, called on nearby Confederate infantry units for help, and with this an all-out battle exploded, with every division of the three Union corps engaged. At the end of a terribly bloody day, neither army had gained an advantage.

THOMAS’S DEFENSE AT THE BATTLE OF CHICKAMAUGA – SEPTEMBER 20, 1863

On the night of September 19, both sides worked feverishly to improve their positions, but while the Union men dug in, James Longstreet’s two divisions arrived to further reinforce Bragg, who, at 9:00 on Sunday morning, September 20, attacked. The Federals held their own for some two hours, but Rosecrans, befuddled by the terrain, lacked an accurate picture of how his units were deployed. By mid-morning, he decided that it was urgently necessary to plug a gap in his right flank and therefore ordered troops from what he believed was his left to plug the gap in the right. But there was no gap. Even worse, thinking he was moving troops from the left to the right, he actually moved them out of the right flank, thereby creating the very gap he had meant to close. Longstreet saw this and launched an attack at the newly opened gap, shattering two Union divisions and driving the Union right onto its left.

Rosecrans and two of his corps commanders, Thomas Leonidas Crittenden (brother of the Confederate general George B. Crittenden) and Alexander McDowell McCook, unable to rally their routed forces, believed a total collapse was inevitable and therefore joined a chaotic retreat to Chattanooga.

George Henry Thomas did not run.

Instead, he rallied units under Brigadier General Thomas John Wood and Brigadier General John Brannan, using them to block Longstreet on the south. Because Bragg had made an all-out attack, holding nothing in reserve, he was unable to exploit Longstreet’s initial breakthrough. In the meantime, Union general Gordon Granger, grasping the significance of Thomas’s bold action, violated his own orders to remain in place to protect the Union army’s flank. Instead, he rushed two brigades to reinforce Thomas, who held the field until nightfall, thereby saving the Army of the Cumberland from annihilation, even in the absence of its commanding officer. For this, he would be hailed as the “Rock of Chickamauga,” a sobriquet bestowed on him by Brigadier General James Garfield.

Thanks to Thomas, the Battle of Chickamauga became a Pyrrhic victory for Braxton Bragg. Although he had driven Rosecrans from the field, his losses exceeded those of the Union: 18,454 killed, wounded, captured, or missing versus 16,170 for the Union. Having achieved a tactical victory, Bragg could not exploit his gains to claim a strategically decisive triumph.

BATTLES FOR CHATTANOOGA, NOVEMBER 23–25, 1863

After Chickamauga, the Army of the Cumberland fell back on Chattanooga, whereupon Bragg deployed his forces in the surrounding mountains and laid siege, seeking to starve the Union out. The desperate situation suddenly riveted Washington’s focus on this theater of the war, and two corps were detached from George G. Meade’s Army of the Potomac and sent west by rail under Joe Hooker. They were transferred from the banks of eastern Virginia’s Rappahannock River to Bridgeport, Alabama, arriving on October 2. In the meantime, William T. Sherman led part of the Union’s Army of the Tennessee east from Memphis, and Ulysses S. Grant was given command of almost all military operations west of the Alleghenies.

During this time, Lincoln and his Cabinet discussed the removal of Rosecrans as commander of the Army of the Cumberland. Secretary of War Edwin Stanton and Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles both agreed that George H. Thomas should replace him, but Lincoln at first hesitated to promote a Virginian. He delayed his decision for nearly a month, until October 19, 1863. Grant’s first telegram to the new army commander was to “hold Chattanooga at all hazards.” The Rock of Chickamauga replied: “We will hold the town till we starve.”

While Union forces prepared to break the siege of Chattanooga, Grant set up the celebrated “Cracker Line” to funnel food and other supplies to the bottled-up Army of the Cumberland. On November 23, Hooker and Sherman commenced the battle for Chattanooga, and on the afternoon of November 25, Grant ordered Thomas to lead the Army of the Cumberland forward from the city to take the Confederate rifle pits at the base of Missionary Ridge south of Chattanooga and east of Lookout Mountain. Grant’s intention was to apply sufficient pressure on Bragg to force him to pull back troops from Sherman’s front on Missionary Ridge; this, he hoped, would allow Sherman to break through. Grant knew the Army of the Cumberland had endured a long, debilitating siege, and he assigned to them a relatively modest mission. But precisely because they had been immobilized for so long, they performed like men who had something to prove. The Army of the Cumberland not only captured the rifle pits as assigned, they kept going, without orders from Grant or from Thomas, charging up the slope of Missionary Ridge and sweeping everything before them. Astoundingly, the soldiers of the Army of the Cumberland broke Bragg’s line exactly where it was the strongest, sending the Confederates into retreat. Gordon Granger, commanding officer of the unit that had so exceeded its orders, exclaimed to an assembly of his men, “You ought to be court-martialed, every man of you. I ordered you to take the rifle pits, and you scaled the mountain!” According to a correspondent who witnessed this exchange, Granger’s “cheeks were wet with tears as honest as the blood that reddened all the route.”

ATLANTA CAMPAIGN, MAY 7–SEPTEMBER 2, 1864

In February 1864, Sherman took charge of three armies: the Ohio, the Tennessee, and the Army of the Cumberland, under Thomas. If he rankled at being subordinated to Sherman, his junior, Thomas did not let on, but he did frequently disagree with Sherman over basic tactics. While Thomas favored making a simultaneous flanking and frontal attack against the Confederate Army of Tennessee (now under Joseph E. Johnston, who had replaced Bragg), in an effort to finish it off once and for all, Sherman wanted to pursue that army toward Atlanta, and so the march to the outskirts of Atlanta consumed 113 days. In this advance, Thomas’s sixty thousand men of the Army of the Cumberland constituted more than half of Sherman’s Atlanta Campaign force.

En route to Atlanta, Thomas fought numerous engagements. Sherman relied on Thomas’s own staff officers to carry out logistics for the entire advance. Thomas played an especially central role in the Battle of Peachtree Creek (July 20, 1864), offering another rocklike stand, against which Lieutenant General John Bell Hood, who had replaced Johnston as commanding officer of the Army of Tennessee, battered fruitlessly, absorbing heavy casualties. Thanks to Thomas’s steadfast work at Peachtree Creek, Hood was unable to break Sherman’s siege of Atlanta.

BATTLES OF FRANKLIN AND NASHVILLE, NOVEMBER 30 AND DECEMBER 15-16, 1864

In the fall of 1864, Grant agreed to allow Sherman to embark on his March to the Sea. Leaving a portion of his armies to garrison Atlanta, Sherman therefore turned away from Hood and advanced on Savannah, sending Thomas with thirty-five thousand men of the Army of the Cumberland west to deal with Hood.

Thomas raced the Confederate general to Nashville, Tennessee, where he would link up with other Union forces in the region. Reaching the city early in November, Thomas made preparations to stand against and defeat the combined forces of Hood and Nathan Bedford Forrest. In the meantime, the XXIII Corps of Major General John Schofield’s Army of the Ohio found itself backed into a vulnerable position at Spring Hill, Tennessee, on November 29. Hood, however, failed to envelop Schofield, who was able to continue his withdrawal toward Thomas. Schofield took up a position at Franklin, and on November 30, Hood, frustrated and impulsive as ever, ordered an ill-advised frontal assault on Schofield. Of some 27,000 men under his command, Hood lost 6,252 killed, wounded, missing or captured, against 2,326 casualties he inflicted on Schofield. The Battle of Franklin won, Schofield continued his withdrawal to Nashville, where he linked up with Thomas. With XXIII Corps attached to it, the Army of the Cumberland now outnumbered Hood nearly two to one.

Grant and others in Union high command understood this. What they could not understand was why, with such a clear numerical advantage, Thomas delayed counterattacking Hood. What Grant perceived as delay, however, was actually a key aspect of Thomas’s tactical style. In sharp contrast with the likes of Hood, he was methodical—perhaps to a fault. As Thomas saw the situation, he was in complete control in and around Nashville. So he took the time he felt necessary to set up a decisive battle.

Back in Virginia, Grant became alarmed and feared that Thomas would allow Hood to slip away. He therefore cut an order relieving Thomas of command but had not yet transmitted it when, on December 15 and 16, Thomas finally attacked. Deploying about fifty-five thousand men against Hood’s thirty thousand, he inflicted some six thousand casualties, killed, wounded, captured, or missing, neutralizing the Confederate Army of Tennessee as a fighting force for the rest of the war and thus accomplishing Sherman’s original mission. The “Rock of Chickamauga” now became known as the “Sledge of Nashville.”

FINAL PURSUIT AND POSTWAR CAREER

Both Secretary of War Stanton and William Tecumseh Sherman sent congratulatory telegrams to Thomas; however, Grant was still oddly dissatisfied with his performance, complaining to Sherman of “a sluggishness” in his pursuit of the defeated Hood after Nashville, which, Grant told Sherman, “satisfied me [that Thomas] would never do to conduct one of your campaigns.” Nevertheless, Stanton wired the news to Thomas that he had been promoted from major general of volunteers to major general in the regular army. Despite this, Thomas felt considerable bitterness toward Grant, whose conduct toward him he considered unwarranted and mean-spirited.

Thomas’s pursuit of Hood ended on December 29, 1864, when Hood was replaced by the very man he had earlier replaced, Joseph E. Johnston. By this point, the Army of Tennessee had been so reduced that it was no longer worth harrying, and Thomas and the Army of the Cumberland engaged in no more major battles before the force was dispersed on May 9, 1865.

In the aftermath of the war and through 1869, Thomas was assigned command of the Department of the Cumberland in Kentucky and Tennessee, with occasional additional command responsibilities in West Virginia and portions of Georgia, Mississippi, and Alabama. This general whose loyalty had been frequently called into question because of his Virginia roots, proved to be an enthusiastic exponent of Reconstruction, acting vigorously to provide protection to freedmen who were menaced by the abuses of white Southern officials and others, including the recently founded Ku Klux Klan.

In 1868, President Andrew Johnson, facing impeachment, sent Thomas’s name to the Senate for promotion to brevet lieutenant general. His intention, clearly, was to position Thomas to replace Grant as general-in-chief, doubtless in a bid to impede Grant’s looming presidential candidacy. Whatever personal resentment Thomas may still have harbored toward Grant, he requested that his name be withdrawn from Senate consideration. It was, he said, a matter of military loyalty, which he was unwilling to sacrifice to politics.

Having taken himself out of consideration to succeed Grant as America’s top soldier, Thomas requested and received command of the Division of the Pacific in 1869. He succumbed to a stroke early the following year, on March 28, 1870, in his headquarters at the Presidio of San Francisco. It was said that, at the time of his collapse, he had been composing a response to a critical article published by John Schofield, who had served under him in Tennessee but had always seen himself as a rival. Burial was at Oakwood Cemetery, in his wife’s hometown of Troy, New York; his body was not welcome in Virginia. None of his Virginia family came north to attend the funeral, his sisters reportedly explaining to their neighbors that “our brother George died to us in 1861.”