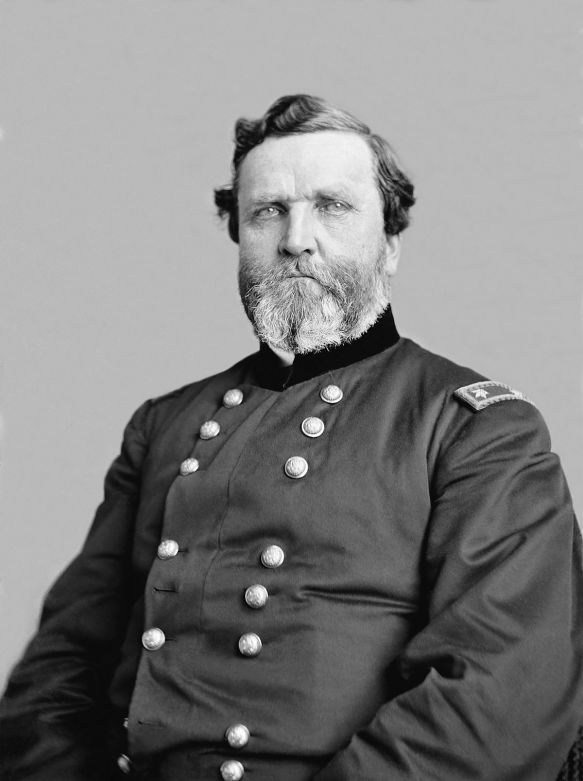

In an era of glory seekers, George H. Thomas put steadfast devotion to duty, perseverance, methodical professionalism, courage, and loyalty above all else. His Virginia birth cost him the rapid promotion to independent command he deserved even as his absolute devotion to the Union cost him his relationship with his Southern family. Deliberate in manner, partly by his nature and partly because of a back injury sustained before the war, his West Point cavalry students nicknamed him “Slow Trot Thomas,” which underscored his methodical approach to combat. This was sometimes confused with uncertainty and delay, even by superiors, such as U. S. Grant, who should have known better. Possessed of a solid tactical and strategic grasp, he was sure and determined in both attack and defense. Unflappable and fearless, his refusal to yield at Chickamauga saved the Union army from disaster there and earned him a far more laudatory sobriquet: the “Rock of Chickamauga.” Ezra J. Warner, long deemed an authority on Civil War biography, judged his combat performance unsurpassed “by any subordinate commander in this nation’s history.”

Just before dawn on August 22, 1831, Nat Turner, fiery lay preacher and slave, led what slaveholding Southerners termed a “servile insurrection,” a fierce rampage that resulted in sixty murders and sent waves of terror throughout the South. It started at the home of Turner’s master, Joseph Travis, in Southampton County, Virginia, as Turner and his cohorts killed every white member of the Travis household. Fanning out into the county, they killed every white person who happened to cross their path. As they swept through the region, more slaves joined in a campaign of mayhem that lasted until the next morning. Among those who fled before Turner and his fellow slaves were fifteen-year-old George Henry Thomas, his sisters, and their widowed mother, all of whom cowered in the woods until the danger had passed.

When the Civil War began in April 1861, the majority of U.S. Army officers were Southerners, most of whom summarily resigned their commissions to join the Confederate forces. If any son of the South would have been assumed to count himself among this number, it was George Thomas, raised on a plantation and nearly the victim of a slave rebellion. For his family, the matter of allegiance was never in question. As with Robert E. Lee and so many others, Virginia, not the United States, was their “country,” and they were shocked when Major George Thomas, U.S. Army, turned down Virginia governor John Letcher’s offer on March 12, 1861, of a post as chief of ordnance in the Virginia Provisional Army. When Southern states had begun to secede in 1860, Thomas was at first ambivalent about his loyalty, but when war actually came, however, Thomas’s Northern-born wife explained that “whichever way he turned the matter over in his mind, his oath of allegiance to his government always came uppermost.”

Once Thomas fully realized his commitment to his oath, he was a rock—that word would come to characterize him—and one of the most tenacious and effective combat leaders in the war. The price he paid was terrible. His family disowned him during the war and refused to reconcile with him after it.

EARLY LIFE AND WEST POINT

He was born the fifth of nine children at Newsom’s Depot, Southampton County, Virginia, just five miles from the North Carolina line. His father, John, was a prosperous and ambitious planter, who worked alongside his three male children and twenty-four slaves to farm his 685 acres. When George was just thirteen, John Thomas died in a farm accident, leaving his large family in straitened circumstances. Despite this and the terror of Nat Turner’s Rebellion, it was said that young George knowingly broke Virginia law by teaching his family’s slaves to read (some historians dismiss this as a legend unfounded in fact).

George Thomas had never intended to follow in his father’s footsteps as a planter. Educated at a local academy, he went to work in the law office of his Uncle James Rochelle. In the end, however, like Ulysses S. Grant, William Tecumseh Sherman, and Joseph Hooker, young men of good families with limited funds, George Thomas found both a means of present sustenance and future career in the United States Military Academy at West Point. In 1836 Congressman John Y. Mason secured his appointment to the Class of 1840. When a grateful Thomas made a special trip to Washington to thank the congressman, he was met by a stern warning: “If you should fail to graduate, I never want to see your face again.” It seems that every other young man from Southampton County Mason had appointed to the academy had failed miserably.

The congressman’s ultimatum would prove to be but the first of many do-or-die military assignments George Thomas would accept.

At twenty when he enrolled, Thomas was sufficiently mature in age and manner to merit the nickname “Old Tom,” and he cultivated friendships with classmates William T. Sherman, Philip Sheridan, William Rosecrans, Don Carlos Buell, Joseph Hooker, and U. S. Grant as well as future Confederate officers Daniel Harvey Hill, Braxton Bragg, and William Hardee. Far from letting Congressman Mason down, he earned a promotion to cadet officer in his second year and performed well enough to come in twelfth in a class of forty-two when he graduated in 1840. This respectable showing was not sufficiently stellar to get him into the engineers—reserved for the very highest achievers—but it did secure him a second lieutenant’s commission in Company D, 3rd U.S. Artillery.

SECOND SEMINOLE WAR AND U.S.-MEXICAN WAR

His first posting was to Fort Lauderdale, Florida, late in 1840 during the Second Seminole War. The mission of the 3rd U.S. Artillery was the same as that of the other army units assigned to Florida: hunt down and round up recalcitrant Seminoles and Creeks and set them marching west to Indian Territory pursuant to the Indian Removal Act of 1830. Since cannon were of no use in this mission carried out in tangled, swampy terrain, Second Lieutenant Thomas led infantry patrols, doing so with sufficient success to merit a brevet promotion to first lieutenant on November 6, 1841.

In 1842, he was transferred to New Orleans, and by 1845 served at Fort Moultrie in Charleston Harbor and Fort McHenry in Baltimore. As war with Mexico began to look inevitable, the 3rd U.S. Artillery was ordered to Texas in June 1845. Thomas was in command of gun crews at the Battles of Fort Brown (May 3–9, 1846), Resaca de la Palma (May 9, 1846), Monterrey (September 21–24, 1846), and Buena Vista (February 22–23, 1847). General Zachary Taylor himself praised “the services of the light artillery” at Buena Vista, and Brigadier General John E. Wool singled out Thomas, without whom “we would not have maintained our position a single hour.” The commander of Thomas’s battery described his “coolness and firmness,” calling “Lieutenant Thomas . . . an accurate and scientific artillerist.” Coolness, firmness, “scientific” accuracy, all these were qualities Thomas would display in one Civil War battle after another. But his heroism at Monterrey was even more predictive of his later combat style. In this urban battlefield, he positioned a cannon in a narrow alley to blast a Mexican barricade. Before long, snipers began picking off his gun crew, whereupon Thomas was ordered to withdraw. He lingered long enough, however, to get off another shot, which repulsed a Mexican infantry charge. Then, instead of abandoning the gun, he and his surviving crew members pulled it out of the alley. Captain Braxton Bragg, with whom Thomas served in Mexico and against whom he would fight in the Civil War, wrote that “no officer of the army has been so long in the field without relief” and characterized his service as “arduous, faithful, and brilliant.” Courage and sheer endurance under fire: These were the fighting hallmarks of George Henry Thomas.

BETWEEN THE WARS

Breveted in Mexico from first lieutenant to captain and from captain to major, he was reassigned in 1849 to duty in Florida. Bragg recommended Thomas for a post as an artillery instructor at West Point, but it was filled by another officer senior to him. When that officer died in 1851, the position became his, and Thomas was additionally assigned as an instructor in cavalry. At the time, Lieutenant Colonel Robert E. Lee, a fellow Virginian, was the academy superintendent, and the two developed a close professional relationship and personal friendship. Among Thomas’s star pupils in cavalry were J. E. B. Stuart and the superintendent’s nephew Fitzhugh Lee, both of whom would become celebrated Confederate cavalry commanders.

While teaching at West Point, Thomas married Frances Lucretia Kellogg, of Troy, New York (November 17, 1852), and was gratified by promotion to regular army captain on December 24, 1853, which carried with it a sorely needed bump in pay.

In the spring of 1854, Thomas left West Point to rejoin his artillery regiment, which was transferred to California. Captain Thomas was put in charge of transporting two companies to San Francisco via ship to the Isthmus of Panama, overland across the stifling and disease-ridden isthmus, then, via another ship, to San Francisco, from which the units embarked on an overland march to Fort Yuma, California, across the Colorado River from Yuma, Arizona.

In 1855, Franklin Pierce’s secretary of war, the future Confederate president Jefferson Davis, formed the 2nd U.S. Cavalry. Historians have long speculated that Davis, believing that civil war was imminent, purposely staffed the new regiment with top-notch officers who were also strongly identified with the South, hoping to create, in effect, a ready-made elite unit for a projected Southern army. Braxton Bragg personally recommended the promotion of Thomas to major and his assignment to the new unit. Presumably, he based his recommendation both on Thomas’s impressive military record and on his identity as an old-line Virginian. Thomas was the third-ranking officer in the regiment, which was commanded by Colonel Albert Sidney Johnston, with Lieutenant Colonel Robert E. Lee as his second in command. Two years later, in October 1857, with Johnston and Lee performing other duties, Major Thomas became acting commander of the regiment and continued as such for two and a half years.

The 2nd was stationed in Texas, where clashes with local Indians were frequent. At Clear Fork, on the Brazos River, Major Thomas was wounded by a Comanche arrow in a skirmish on August 26, 1860. The arrow passed through the fleshy part of his chin and lodged in his chest. He responded by pulling itout himself and then summoning the surgeon, who made a hasty field dressing, after which the major resumed his place at the head of the patrol.

Although he had been in the thick of battle in Mexico and would again be so during the Civil War, the arrow shot was the only combat wound Thomas ever received. However, in November 1860, during a leave of absence in which he journeyed back to Virginia to see his family, he suffered a freak accident at Lynchburg, when he fell from a train-station platform. He injured his back so severely that he thought he would have to close his military career; he recovered but was doomed to suffer from nearly debilitating back pain for the rest of his life.

His injury was not his only concern on this trip. As the nation hurtled toward dissolution, he agonized over reconciling his loyalty to the U.S. Army and the government it served with his Virginia birth and the sentiments of his Virginia family. He must have known that this could be the last time he would visit his siblings. After staying with them, he boarded a northbound train, intending to visit his wife’s family in Troy. He made it a point, however, to stop over in Washington, so that he could inform General-in-Chief Winfield Scott that Major General David E. Twiggs, in command of the Department of Texas, was a secessionist whose allegiance to the U.S. Army could not be relied upon. Clearly, Thomas was preparing to choose the Union over the Confederacy.

OUTBREAK

Despite the information he gave Scott, many in the U.S. government and the army doubted Thomas’s loyalty. It is true that as late as January 18, 1861, three months before Fort Sumter, Thomas applied for the post of superintendent of the Virginia Military Institute (VMI), yet he also turned down Governor Letcher’s offer in March to become ordnance chief of the Virginia Provisional Army. When Virginia seceded on April 17, 1861, days after the fall of Fort Sumter, Thomas made his absolute decision to fight for the Union. With ritual solemnity, his sisters turned his portrait to the wall and burned every letter he had ever written to them. His West Point cavalry pupil J. E. B. Stuart was equally unsparing in his condemnation, writing to his wife on June 18 that he “would like to hang, hang him as a traitor to his native state.”

Of the thirty-six officers of the 2nd U.S. Cavalry, nineteen, including Johnston, Lee, and Hardee—resigned their commissions to join the Confederate army, a circumstance that catapulted Thomas through a rapid series of promotions, to regular army lieutenant colonel on April 25 (replacing Lee) and colonel on May 3 (replacing Johnston) and to brigadier general of volunteers on August 17.

WAR AND POLITICS

Even before he was officially promoted to brigadier general, Thomas led a brigade under Major General Robert Patterson in the Shenandoah Valley during the First Bull Run Campaign but was immediately thereafter transferred to the Western Theater. In Kentucky, he reported to Major General Robert Anderson, who assigned him to train the raw recruits who had answered President Lincoln’s call for short-term volunteers. Soon after this, on December 2, 1861, he was assigned independent command of a group of five understrength brigades consolidated as the First Division of Don Carlos Buell’s Army of the Ohio.

On January 19, 1862, Thomas led four brigades—4,400 men—of the First Division in its first battle, against 5,900 Confederates led by George B. Crittenden at Mill Springs, Kentucky. Thomas achieved a quick victory with few casualties (39 killed, 207 wounded), which blunted the Confederate threat from east Tennessee and sent a thrill of elation through a Union public whose morale had been sorely tested by Bull Run and the other defeats that followed. It was the first significant Union victory of the war.

In what would become something of a pattern in the war, Thomas received remarkably little credit for his achievement while four colonels under him were elevated to brigadier general. It is likely that, despite his superb performance, higher command, Lincoln included, still distrusted the Virginian. Nevertheless, he was sent with his division to Shiloh, to reinforce Grant at that nearly disastrous battle, but arrived on April 7, just as the second day’s combat had come to an end.

Although he had missed the battle, he benefited from the reorganization of the Department of the Mississippi that Henry Wager Halleck engineered to squeeze Grant (whose losses at Shiloh unnerved Halleck) out of field command. The department’s three armies were juggled and transformed into three “wings.” Seeing to it that Thomas was promoted to major general of volunteers, Halleck assigned him to command right wing, which consisted of four divisions of what had been Grant’s Army of the Tennessee plus one division from the Army of the Ohio. William T. Sherman became Thomas’s subordinate, and neither he nor Grant ever fully forgave Thomas for what they regarded as his usurpation of their rightful authority.

With Grant out of the way, Halleck assumed field command of some 120,000 men. The center was under Buell’s command, the left under that of Major General John Pope, and the right led by Thomas. Major General John McClernand commanded the reserve. Under Halleck’s sluggish leadership and hampered by the mediocrity of Buell, Pope, and McClernand, Thomas could do very little. Halleck’s massive forces arrived at Corinth only after the Confederates had withdrawn, making the occupation of this town a hollow victory. Lincoln kicked Halleck upstairs by naming him general-in-chief of the Union armies, replacing George B. McClellan, and, with his departure, Thomas was made acting commander of the Army of the Tennessee at Corinth until June 10, when Grant was restored to field command. Turning Corinth and the army over to Grant, Thomas led his First Division to link up with the Army of the Ohio under Buell, who had direct orders from Lincoln to advance against Chattanooga and Knoxville.

Buell proved to be in the Western Theater what McClellan was in the East: supremely reluctant to go on the offensive. General-in-Chief Halleck offered command of the Army of the Ohio to Thomas, who, unwilling to behave in any manner that seemed disloyal to Buell, a longtime friend and comrade-in-arms, refused the promotion. He served as Buell’s second in command at the Battle of Perryville, Kentucky, on October 8, 1862, a bloody contest in which Buell was poised to annihilate Braxton Bragg’s army but was unable to coordinate the disparate units of his sixteen-thousand-man force. Thomas did not engage until mid-afternoon, by which time the critical moment had passed and Bragg was preparing to slip away. In the end, Buell garnered some credit in the popular press for driving Bragg out of Kentucky (though he had taken substantially heavier casualties than Bragg), credit he generously shared with Thomas. Halleck and Lincoln didn’t see Buell as victorious, however, and he was relieved. This time, when Thomas’s name again came up as his replacement, Lincoln countered with that of William Rosecrans. The president acknowledged that Thomas had shown himself to be aggressive—which was precisely the kind of commander he always clamored for—but he was a Virginian, and Lincoln was reluctant to replace the Virginian Buell with the Virginian Thomas. Besides, Rosecrans was Catholic, which, Lincoln believed, would be helpful in generating support for the war among Catholics, especially such immigrant groups as the Irish. Thus the president sacrificed the very military quality he had missed in McClellan and Buell—a willingness to fight—in order to achieve certain political ends.