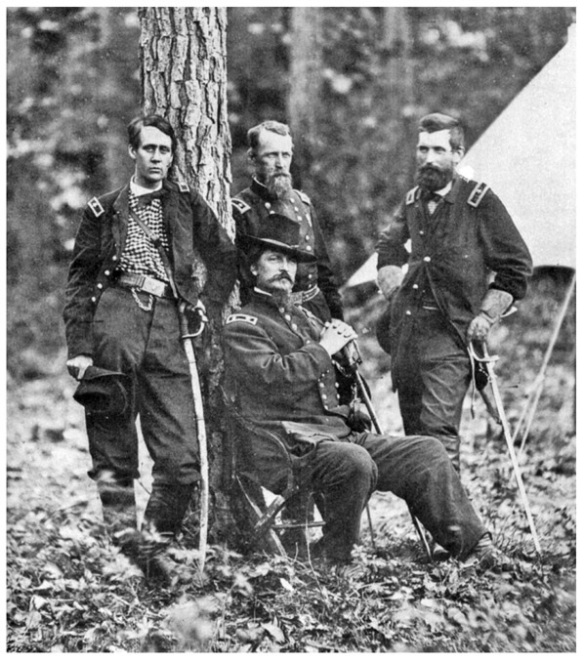

Hancock with his division commanders at Cold Harbor, Virginia, 1864. Standing from left to right: Francis C. Barlow, David B. Birney, and John Gibbon. Hancock is seated.

FREDERICKSBURG AND CHANCELLORSVILLE, DECEMBER 11–15, 1862 AND APRIL 30–MAY 6, 1863

What Hancock did achieve at Bloody Lane was sufficient to get him a promotion to major general of volunteers on November 29, 1862. By this time, however, President Lincoln had once again relieved McClellan (if Hancock had exceeded his orders from McClellan, he might have saved his commanding officer’s job), and Hancock was leading his newly acquired division in an Army of the Potomac commanded by Ambrose Burnside.

Like most of the officers and men of the Army of the Potomac, Hancock was not happy about McClellan’s removal. Unlike many of them, however, he was determined to give the new commander his full loyalty. He believed, he said, that “we are serving no one man: we are serving our country.”

But his determination to serve his country by demonstrating loyalty to the new commander was soon sorely tested. Learning of Burnside’s plan to make a frontal assault against thoroughly entrenched Confederate positions, including artillery, on Marye’s Heights at Fredericksburg, Hancock could not stop himself from protesting its suicidal foolishness. Hearing of this, Burnside summoned Hancock to remind him of his obligation to execute without complaint whatever orders his commanding general might give. Hancock agreed but pointed out that the proposed objective was extraordinarily difficult. Burnside nevertheless stood firm on his plan, and when Hancock received his orders to attack at eight o’clock on the morning of December 13, 1862, he followed his orders.

Between his division’s starting position and the stone wall at the foot of Marye’s Heights were some 1,700 feet of flat, open, exposed plain, all thoroughly raked by fire from Confederate artillery and muskets dug in on the high ground. To advance across this expanse was to walk into death itself. But Hancock led his men across. A Confederate bullet sliced through his coat and grazed his abdomen. Had he walked a split second faster, he would have been dead. As it was, the wound did not stop him. Hancock shuttled back and forth across the exposed plain, through the ceaseless storm of musket and cannon fire, always urging his men forward.

His exertions were sufficient to drive the soldiers of his division closer to the stone wall than any other Union troops that terrible day. But, like the rest, Hancock’s men were forced to break off and retreat.

“Out of the fifty-seven hundred men I carried into action,” he wrote the next day, “I have this morning in line but fourteen hundred and fifty.”

As Second Bull Run had cost Pope his command and Antietam had spelled the end for McClellan, so Fredericksburg brought the relief of Ambrose Burnside and his replacement by Joseph Hooker. Hooker’s plan was to return to Fredericksburg, attack far more intelligently and with greater numbers, and in this way break through to advance at long last against Richmond.

The plan, Hancock believed, was sound, yet he had overheard Hooker declare to another general the day before the fight that “God almighty could not prevent me from winning a victory tomorrow.” And that made Hancock doubt. “Success,” this son of a Baptist deacon wrote, “cannot come to us through such profanity.”

Profane and blustering as he was, Hooker had a good plan and outnumbered Lee by two to one. His problem was that he lost his nerve in the execution, and instead of pushing Lee out of Fredericksburg, he relinquished the initiative by waiting for him at Chancellorsville.

Hancock’s chief contribution to the disastrous battle that resulted was to use his division with great skill and courage to cover the withdrawal of the Army of the Potomac. In the course of carrying out this operation, he was wounded by shell fragments, his injuries adding to the heavy sense of depression this latest defeat had loaded upon him. “I have had the blues ever since I returned from the campaign,” he admitted in a letter to Allie.

BATTLE OF GETTYSBURG, JULY 1–3, 1863

Hancock endured his “blues.” But for some commanders, it was beyond endurance. After Chancellorsville, Major General Darius Crouch, commanding officer of II Corps, requested to be relieved of command. On May 22, command of II Corps was awarded to Winfield Scott Hancock.

He established an immediate rapport with these veterans who, like the rest of the Army of the Potomac, had fought hard, deserved triumph, and yet suffered nothing but wounds, deaths, and heartbreak. As when he commanded a brigade and then a division, corps commander Hancock took steps to make himself personally known to his officers and men and to get to know them with the same degree of intimacy. Captains and lieutenants were amazed that the commanding general singled them out, saluted, and addressed them by name.

As Lee’s victory at the Second Battle of Bull Run emboldened him to invade Maryland, so his victory at Chancellorsville propelled him to invade Pennsylvania. George Meade, newly appointed to replace Hooker as commanding general of the Army of the Potomac, led his troops to intercept Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia. Contact between the two forces came at a crossroads town called Gettysburg, and the first day of battle, July 1, 1863, began badly for the Union. Major General John Reynolds, a good friend of Hancock’s and universally respected—many believed he, not Meade, should have been placed at the head of the Army of the Potomac—had control in the field. On his arrival at the front, the army cheered, only to fall into stunned silence when Reynolds was killed a few moments after his arrival.

Hearing the news, Meade summoned Hancock. He told him that he needed a replacement for Reynolds, a man who would take control and restore the situation until the bulk of the army arrived at Gettysburg. Hancock responded by reminding Meade that Major General O. O. Howard was senior to him and next in line for the command. But Meade knew what he wanted. He replied to Hancock that he understood but had made his choice.

By a stroke of death and decision, Winfield Scott Hancock assumed effective command of the entire left wing of the Army of the Potomac, consisting of his own II Corps plus I, III, and XI Corps. When Howard disputed Hancock’s authority, Hancock quickly asserted himself and set about organizing the critical Union defenses on Cemetery Hill. The Confederates, who at this point outnumbered the Union forces at Gettysburg, were relentlessly driving I and XI Corps back through the streets of Gettysburg. That, Hancock decided, was acceptable. But the high ground at Cemetery Hill had to be held at all costs. Lose the high ground, and the battle would be lost. Acting on the authority Meade had given him to withdraw the forces holding the town proper, Hancock ordered I and XI Corps to fall back on Cemetery Hill, to take a stand there, and to fight it out there.

Thus when Meade arrived after midnight to assume direct command, the contour of the Battle of Gettysburg had already been determined—by Hancock. The morning of July 2 found Hancock’s II Corps occupying Cemetery Ridge, in the center of the Union line. Lee attacked both ends of the line. Union III Corps, on the left, absorbed a terrific blow dealt by Lieutenant General James Longstreet. To meet this assault, Hancock sent his own 1st Division, commanded by Brigadier General John C. Caldwell, to reinforce III Corps in a place called the Wheatfield. At the same time, Confederate Lieutenant General A. P. Hill led his corps against Hancock at the Union center. With extraordinary agility, Hancock shuttled and rushed units to each critical point as they developed. Looking to save the army, he sacrificed the 1st Minnesota Regiment by sending it to attack an entire brigade—representing about four times more men than were in the regiment—a suicide mission (the Minnesotans took 87 percent casualties, killed, wounded, or missing) that nevertheless bought Hancock the time he needed to re-form the Union line.

Throughout the second day, Hancock often personally led reinforcing units as needed. He seemed to be everywhere, and when III Corps commander Daniel Sickles was wounded, Meade added III Corps to Hancock’s command. Now directly controlling all of the Union line from Cemetery Hill to Little Round Top, Hancock kept the defense both strong and flexible, so that, by the end of July 2, the Battle of Gettysburg had yet to be decided.

July 3 found Hancock still holding his center position on Cemetery Ridge. His II Corps absorbed the main impact of Pickett’s Charge—the twelve-thousand-man frontal assault Lee desperately hoped would dislodge the Union from the high ground. It had been preceded by a horrific artillery bombardment, most of it concentrated against Union II Corps. During the pounding, Hancock rode back and forth along his lines to keep his troops in place. “General,” one subordinate officer protested, “the corps commander ought not to risk his life that way.” Hancock replied: “There are times when a corps commander’s life does not count.”

PICKTT’S CHARGE AT GETTYSBURG – JULY 3, 1863

In the end, Pickett’s Charge proved both futile and tragic. Among its casualties was Brigadier General Lewis A. Armistead, who led a brigade in Pickett’s division. Severely wounded in the charge, he would die two days later.

Hancock learned of his friend’s wounding as he himself lay painfully injured. On July 3, a Confederate bullet had ricocheted off the pommel of his saddle. The bullet tore into his inner right thigh, pushing through wood splinters and one bent nail from the shattered pommel.

“My eyes were upon Hancock’s striking figure,” a Lieutenant George Benedict recalled, “when he uttered an exclamation, and I saw that he was reeling in his saddle. General Stannard bent over him as we laid him on the ground, a ragged hole an inch or more in diameter, from which blood was pouring profusely, was disclosed in the upper part of his thigh.” Aides applied a tourniquet, and Hancock, quite conscious, pulled out the nail himself. “They must be hard up for ammunition,” he commented, “when they throw such shot as that.” Hancock asked his aides to prop him where he lay on Cemetery Hill so that he could continue to direct the battle.

In the meantime, Captain Henry H. Bingham, one of his staff, brought the news of Armistead’s wound and reported that it was mortal. He conveyed to Hancock a message from his friend. “Tell General Hancock for me,” Armistead had said, “that I have done him and done all an injustice which I shall regret or repent the longest day I live.” Bingham then handed to Hancock Armistead’s spurs, pocketbook, watch and chain, and a personal seal, explaining that the Confederate general had wanted him to have these.

Hancock allowed himself to be evacuated only after he was certain the Battle of Gettysburg had been won. Armistead would die within two days. Hancock would recover slowly but never completely. Meade had entrusted most of the conduct of the battle to him. Only when Hancock urged a full counterattack after Pickett’s Charge had been repulsed did Meade overrule him. It was a serious error on Meade’s part, since it allowed Lee to begin his withdrawal, his Army of Northern Virginia badly beaten but still intact, back into Virginia. “My God,” President Lincoln would moan after he’d heard that Meade had allowed Lee to slip away, “is that all?”

OVERLAND CAMPAIGN, MAY–JUNE 1864

Hancock convalesced at his father’s house in Norristown, returning to limited duty as a recruiting officer during the winter of 1863–1864, then resuming field command of II Corps in the spring, in time to march in Grant’s Overland Campaign.

Although those who knew Hancock reported that his wound and long convalescence had diminished his former passion and energy, his corps performed extraordinarily well at the Battle of Spotsylvania Court House (May 8–21, 1864), achieving a breakthrough at the so-called Bloody Angle in the assault on the Mule Shoe salient. The Confederates’ vaunted Stonewall Brigade was splintered, most of those who weren’t killed becoming prisoners. Indeed, II Corps captured some three thousand men in Richard Ewell’s corps.

II Corps was next committed to Grant’s ill-conceived assault at Cold Harbor (June 3, 1864), where it absorbed the brunt of the slaughter, losing more than 3,500 men, killed, wounded, or captured. Already battered in its long service with the Army of the Potomac, II Corps would never be restored to its full strength after Cold Harbor.

SIEGE OF PETERSBURG, JUNE 9, 1864–MARCH 25, 1865

Hancock had known the awful bitterness of being the victim of his commanders’ blunders, from McClellan, to Pope, to Burnside, to Hooker, and now even Grant at Cold Harbor. After Cold Harbor, Grant did what he had done after the Battles of the Wilderness and Spotsylvania Court House. Though defeated, he sidestepped Lee and the Army of Virginia and, instead of retreating, advanced, forcing Lee to stretch his deteriorating lines yet thinner. As the Army of the Potomac trudged across the James River, Hancock’s II Corps was positioned to make an assault against Petersburg, which was weakly defended because Lee, assuming Grant intended to attack Richmond, had shifted troops from the Petersburg front to the Confederate capital. Had Hancock struck and struck hard, the war would surely have ended much sooner than it did. Instead, he deferred to XVIII Corps commander “Baldy” Smith, who wanted to delay action until all of the men were consolidated in position and rested. Had Hancock been less depleted by the lingering effects of his Gettysburg wound and the carnage of Spotsylvania and Cold Harbor, he might have acted in spite of Smith’s counsel. But he did not, and by the time Grant and the bulk of the Army of the Potomac arrived at the Petersburg front, Lee had reinforced it, and the opposing armies settled in for a siege that would last until early spring of the next year.

During the long siege, Hancock led his corps in the two battles of Deep Bottom (July 27–29 and August 14–20, 1864), both feints toward Richmond intended to draw Confederate forces away from Petersburg so that Grant might effect a breakthrough. The Confederate defenders prevailed in both encounters, however. Nevertheless, Hancock’s accumulated record of achievement was recognized by his promotion to brigadier general in the regular army on August 12, 1864.

After the Second Battle of Deep Bottom, Hancock led II Corps south of Petersburg to destroy the tracks of the Wilmington and Weldon Railroad in an ongoing effort to ensure that the city was totally cut off. Hancock committed a rare blunder, leaving his position exposed at Reams’s Station, where Confederate generals Henry Heth and A. P. Hill attacked on August 25, inflicting on the roughly nine thouand II Corps men engaged 2,747 casualties, including 2,046 captured or missing. Confederate casualties in this lopsided battle were light, 814 killed, wounded, or missing out of eight to ten thousand engaged. Hancock blamed himself for having deployed his men in a faulty manner, but he was far more appalled by their performance under fire. They crumbled, broke, and ran—despite his own efforts to rally them, which included, as usual, deliberately exposing himself in the teeth of enemy fire.

The truth he was forced to face was stunning. His beloved corps had at last been broken. In November, when his Gettysburg wound, never having fully healed, partially reopened, the debilitated and depressed Hancock resigned field command.

COMMANDER, FIRST VETERANS CORPS

Hancock was assigned to command the garrison at Washington, D.C., and to create and command a ceremonial First Veterans Corps. On March 13, 1865, he was promoted to brevet major general in the regular army in somewhat belated recognition of his heroism at Spotsylvania.

His new duties were comparatively light, but, following the assassination of President Abraham Lincoln and the subsequent trial and conviction of John Wilkes Booth’s conspirators, Hancock was charged with carrying out the group execution—by hanging on July 7, 1865—of Lewis Powell, David Herold, George Atzerodt, and Mary Surratt. Hancock believed that Surratt’s sentence was a gross miscarriage of justice, and he was so hopeful that it would be commuted at the last minute that he stationed a relay of couriers between the gallows at Fort McNair and the White House. To the judge who presided over the trial and pronounced the death sentence on Mrs. Surratt, Hancock remarked that he had “been in many a battle and [had] seen death, and shell and grapeshot, and, by God, I’d sooner be there ten thousand times over than to give the order this day for the execution of that poor woman.” He paused, then continued: “But I am a soldier, sworn to obey, and obey I must.”