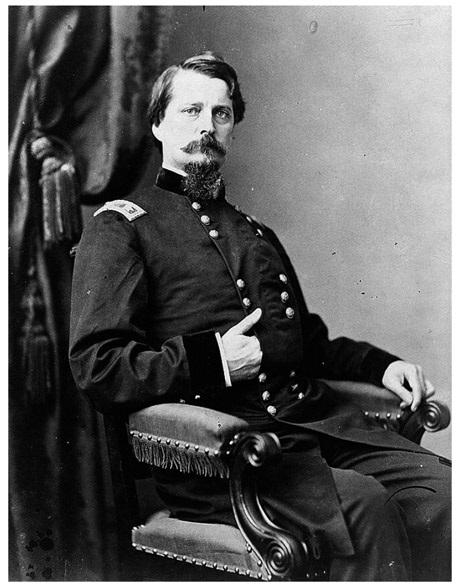

In his Personal Memoirs of 1885, Ulysses S. Grant gave what may be the most comprehensive concise evaluation of Winfield Scott Hancock. He stands, Grant wrote, as “the most conspicuous figure of all the general officers who did not exercise a separate [that is, army-level] command. He commanded a corps longer than any other one, and his name was never mentioned as having committed in battle a blunder for which he was responsible. He was a man of very conspicuous personal appearance. . . . His genial disposition made him friends, and his personal courage and his presence with his command in the thickest of the fight won for him the confidence of troops serving under him. No matter how hard the fight, the 2d corps always felt that their commander was looking after them.”

Hancock always fought under the command of others, and no field officer was more universally admired than he, who emerged from the Civil War as perhaps the model soldier-general. He is deservedly most celebrated for the leading role he took at Gettysburg, where his command decisions and personal presence on days one and two made Union victory possible, and his sacrifices on day three ensured the defeat of Lee.

On February 14, 1824, Elizabeth Hoxworth Hancock of Montgomery Square, Pennsylvania, gave birth to identical twin boys. One was given the name Hilary Baker and the other Winfield Scott. That a boy should be named for family relations, in the case of Hilary Baker, was hardly unusual, but to name his twin brother not after relatives but a soldier—a hero of the War of 1812 who was just entering mid-career by 1824—was rare in early nineteenth-century America. Most Americans had an innate dislike of standing armies and professional military men (the quartering of troops had played a big part in triggering the American Revolution). What is more, the Hancocks were hardly a military family. Father Benjamin was a schoolteacher who studied law and would soon become a lawyer, while Mother Elizabeth worked as a milliner. It was, therefore, almost as if, in naming their son, the Hancocks had inadvertently predicted his destiny. From childhood, he would exhibit an early fascination with things military, and, as an adult, he would prove to be a kind of natural and instinctive soldier and leader of soldiers. In the U.S.-Mexican War, his first experience of battle, he would even serve directly under his namesake. And in the Civil War, he would earn the romantic warrior sobriquet of “Hancock the Superb.”

EARLY LIFE AND WEST POINT

A few years after the Hancock twins were born, the family moved from Montgomery Square, outside of Lansdale, to Norristown, where Benjamin Hancock began practicing law. He also became increasingly prominent in local Democratic politics and served with great devotion as a deacon in the Baptist church. The twins were educated at Norristown Academy until a public school opened up in town late in the 1830s. As boys, they were inseparable, yet identical only in physical appearance. While Hilary was quiet and well-behaved, the boisterous Winfield often got into trouble of the boys-will-be-boys variety. His conduct, however, was not so naughty as to disqualify him from the dose of higher education his school grades merited, and his rapidly developing interest in the military—he organized a military company among his classmates—prompted his father to call in a political favor from the local congressman, Joseph Fornance.

In 1840, Fornance obliged Benjamin by nominating Winfield to the U.S. Military Academy at West Point.

Already tall—he was six-foot-two in an era when five-foot-seven was average for a man—handsome, and soldierly in appearance, Winfield Scott Hancock was also a genial and popular cadet. His academic performance was, however, on the lower end of average. Graduating eighteenth in the twenty-five-cadet Class of 1844, he was automatically sent to the infantry and commissioned in the 6th Regiment, assigned to serve in Indian Territory.

INDIAN TERRITORY, RECRUITING DUTY, AND THE U.S.-MEXICAN WAR

For the next two years, little happened in the Red River Valley, Hancock’s corner of Indian Territory, and he saw nothing of combat before he was sent back east to recruiting duty in Cincinnati, Ohio, and across the river in Kentucky. While he was there, the U.S.-Mexican War began in Texas and California, prompting Hancock to request his immediate return to the 6th Regiment, which was stationed in the thick of the developing action. The problem was that the good-looking and genial Hancock had proved to be a talented recruiter, not only signing up more than his quota of men, but also knowing which men to reject. He was just too good at his job, and the army wanted him to continue in it as long as possible. Orders to rejoin his regiment did not come until May 31, 1847.

To Second Lieutenant Hancock’s vast relief, there was still plenty of war to be fought when he rejoined the 6th at Puebla, Mexico, as it served in the invading army led by his namesake, Major General Winfield Scott.

From Puebla, the army advanced to Contreras, which became Winfield Scott Hancock’s maiden battle on August 19 and 20, 1847. By the afternoon of August 20, the battle had moved to Churubusco. Here Hancock suffered his first wound—a shallow musket ball penetration below the knee—yet he not only kept fighting, but took over command of his company after its commander was felled by a more grievous wound. Hancock’s gallantry and initiative at Churubusco earned him a brevet to first lieutenant, and in both Contreras and Churubusco, he served alongside three officers who would become notable Confederate generals, James Longstreet, George Pickett, and Lewis Armistead—a man with whom Hancock also developed a close personal friendship.

The wound Hancock sustained at Churubusco became infected and resulted in a fever. Despite this, he fought at Molino del Rey (September 8, 1847) but was laid up during the culminating battle of the war, Chapultepec (September 12–13), and the subsequent occupation of Mexico City. That these momentous events should have passed him by was a source of lifelong regret.

PRELUDE TO THE CIVIL WAR

Hancock and his regiment remained in Mexico until after the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo was signed in February 1848. Having earned a reputation as an able administrator while he served as a recruiter, Hancock was next assigned to a number of quartermaster and adjutant postings, including at Fort Snelling, Minnesota, and St. Louis, Missouri. In this city, he met Almira Russell, whom he married on January 24, 1850. “Allie” was universally admired by Hancock’s fellow officers for her beauty, charm, and kindness, and when he was promoted to captain in 1855 and transferred to Fort Myers, Florida, she and their five-year-old son accompanied him—she the only woman on this primitive post. Although the sporadic fighting of the Third Seminole War was under way, quartermaster Hancock saw no combat.

He was transferred again, this time to Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, in 1856, during the height of the “Bleeding Kansas” guerrilla violence between proslavery and antislavery factions. Hancock saw relatively little of the bloodshed, however, before he was tasked with helping to prepare an expedition to Utah Territory to put down the so-called Mormon Rebellion, an antigovernment uprising, which included the Mountain Meadows massacre of September 11, 1857, in which the Mormon Militia and their Paiute Indian allies killed more than 120 non-Mormon California-bound settlers. By the time Hancock and the 6th Infantry arrived, however, the conflict was over, and Hancock was told that he was being sent to a new posting with the 6th in Benicia, California.

Obtaining a leave of absence, he traveled back east to fetch his wife, who had given birth to a second child, a daughter, before he left for Utah. For the first time in their lives together, Allie was reluctant to follow her husband, but she was gently counseled by none other than Colonel Robert E. Lee, who persuaded her that an army officer needed his wife and family to be with him, if at all possible. Thus the family made the arduous journey to California together. At Benicia, in the San Francisco Bay area, they were presented with orders to travel even farther, down to Los Angeles, some four hundred miles to the south. Here they remained, Captain Hancock serving as assistant quartermaster under future Confederate general Albert Sidney Johnston, and here Hancock formed his close friendship with Armistead.

When news of the outbreak of the Civil War reached Los Angeles in the spring of 1861, Johnston, Armistead, and the other Southern officers who had decided to resign their commissions and join the Confederate cause gathered at the Hancock home for a farewell party. Almira Hancock later recalled that Major Armistead was “crushed . . . tears . . . streaming down his face.” He laid his hands upon her husband’s shoulders, she wrote, and looked him “steadily in the eyes.” “Hancock,” he said, “good-bye. You can never know what this has cost me.”

Armistead then turned to Allie and placed in her hands a small satchel filled with keepsakes to be sent to his family if he should be killed. There was also a little prayer book, which he said was for her and her husband. On its flyleaf he had inscribed: “Trust in God and fear nothing.” Before he left that evening, Armistead also offered Hancock his major’s uniform, but the captain could not bring himself to accept it.

INTO WAR

Like his Southern comrades, Winfield Scott Hancock was also determined to leave California—in his case, however, to serve with the Union. Since the end of the war with Mexico, he had been studying the campaigns of history’s “great captains,” from Julius Caesar to Napoleon Bonaparte, and he hoped that he would not only receive a speedy transfer back east, but would also exchange his administrative duties for a combat assignment.

He was sent to Washington but was instantly loaded down with quartermaster work for the Union army, which, by the late summer of 1861, was rapidly expanding. George B. McClellan, however, soon picked out Hancock’s name from a list of officers. He remembered him from West Point as well as from the Mexican war, and he recognized him as a courageous, intelligent, and skilled officer. Thanks to McClellan, Hancock was, on September 23, 1861, jumped from captain to brigadier general (and thus would not have had use for the major’s uniform he had declined to accept from Armistead) and assigned to command an infantry brigade in a division under Brigadier General William F. “Baldy” Smith in McClellan’s Army of the Potomac.

McClellan soon realized that he had every reason to be pleased with his choice of Hancock. The man was a thoroughgoing military officer, who prized military discipline but also understood men and how to motivate them on a human level. In contrast to most of his regular army colleagues, he enjoyed working with volunteers, whom he did not regard as necessarily inferior to regular army troops. Treated with respect and confidence, these citizen soldiers gave Hancock their very best in return.

BATTLE OF WILLIAMSBURG, MAY 5, 1862

Thanks to General McClellan’s dilatory approach to campaigning, the Confederates were able to withdraw from their positions at Yorktown, Virginia, before the Army of the Potomac closed in on them during the Peninsula Campaign. A division under Joseph Hooker opened the Battle of Williamsburg on May 5 by attacking an earthen fortification known as Fort Magruder. He was repulsed, however, and Confederate general James Longstreet followed up the repulse with a counterattack on the Union left. A Union division under Brigadier General Philip Kearny arrived in time to blunt the counterattack and stabilize the Union position as Hancock led his brigade in a spectacular encircling movement against the Confederate left flank, forcing the enemy to abandon two key redoubts, which Hancock’s men occupied.

McClellan both recognized and appreciated what Hancock had done and even telegraphed Washington to report that “Hancock was superb today,” thereby giving birth to the sobriquet he would carry with him through the rest of the war, “Hancock the Superb.” Yet, being McClellan, he declined to exploit the counterattack. Instead of following up on what Hancock had gained, McClellan released the pressure, allowing the Confederates, now on the defensive, to withdraw intact.

BATTLE OF ANTIETAM, SEPTEMBER 17, 1862

A subordinate commander, Winfield Hancock was perpetually at the mercy of those above him, and his tactical achievement at Williamsburg came to nothing strategically as McClellan’s Peninsula Campaign shriveled on the vine. McClellan was ordered to withdraw north to link up his Army of the Potomac with John Pope’s newly formed Army of Virginia, and because McClellan moved slowly, Pope and his army were left cut off and vulnerable to Robert E. Lee at the Second Battle of Bull Run (August 28–30, 1862).

With Pope’s failure, President Lincoln reluctantly recalled McClellan to top field command, and when Lee invaded Maryland in September 1862, Hancock found himself deep in the blood of Antietam. After 1st Division, II Corps commander Major General Israel B. Richardson fell mortally wounded, Hancock assumed divisional command, making a magnificent entrance, galloping at top speed, staff in train, between the division’s troops and the enemy, parallel to the Sunken Road that had been transformed by desperate battle into “Bloody Lane.” Deliberate exposure to enemy fire was and would always be part and parcel of the Hancock style of command.

The men of the division were impressed and inspired. As Hancock’s adjutant Francis Walker later wrote, “An hour after Hancock rode down the line at Antietam to take up the sword that had fallen from Richardson’s dying hand, every officer in his place and every man in his ranks was aware, before the sun went down, that he belonged to Hancock’s division.”

It was a magnificent display of what modern officers call “command presence,” and yet Hancock did not fully exploit it. He had his men in the palm of his hand and might have led them in highly effective counterattacks against the Confederates, who were by this time thoroughly exhausted. Instead, he clung to and carried out the orders McClellan had given him, which were to do no more than hold his position. He did what he had been told. Bold as Hancock was, an even bolder combat leader would have given his commander more than he had asked for and, in so doing, might have transformed a narrow Union victory into a decisive triumph.