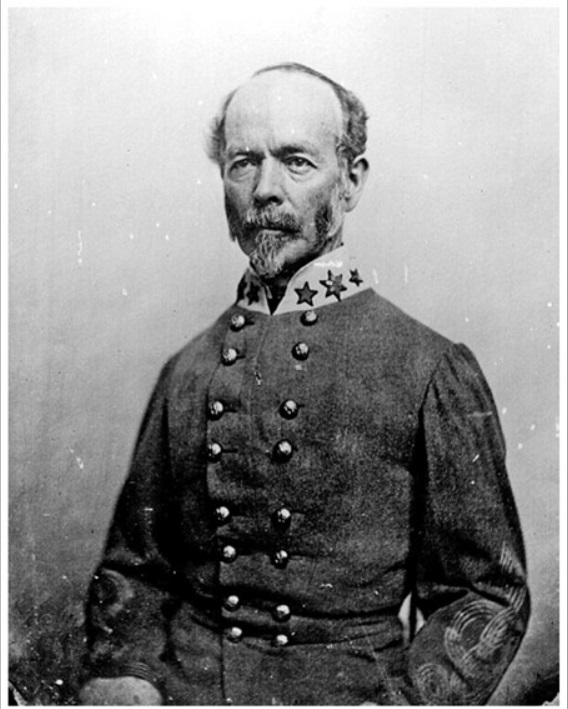

Two classes of men were convinced that Joseph E. Johnston was among the greatest generals of the Civil War: those who served under him and those, including Ulysses S. Grant and William T. Sherman, who fought against him. Others, Confederate president Jefferson Davis foremost among them, believed his lack of aggressiveness cost him—and the Confederacy—victory in every campaign he led.

Military historians are divided in opinion. Some hold that, had Johnston received adequate support instead of criticism and interference from Davis, his careful, prudent approach to war-fighting, which substituted maneuver for battle, might have positioned the South to avoid unconditional surrender. Others condemn him in the harshest way they can: by describing him as the Confederate George McClellan.

Joseph E. Johnston was the only general officer of the United States Army to resign his commission and fight for the Confederacy. Fellow Virginian Robert E. Lee, the next highest-ranking U.S. Army officer to resign, was a colonel when Johnston had been a brigadier general. In theory, therefore, Johnston was the Confederacy’s senior ranking officer.

But the Civil War killed theories as prodigally as it killed men. Despite a glorious record of combat, Johnston was U.S. Army quartermaster general—in essence, the chief supply clerk—when he left. It was a fact that President Jefferson Davis used to justify listing him fourth behind the other full generals whose appointments he announced in the autumn of 1861. Samuel Cooper (who would never see combat), Albert Sidney Johnston (no relation to Joseph), and Lee were all senior to him. Thus Joseph E. Johnston entered the Civil War angry and unhappy, feeling the weight of insult and injustice, his working relationship with Davis poisoned from the outset, and his credentials—his very fitness—as a combat commander cast into deep doubt.

A SON OF OLD VIRGINIA

Like Robert E. Lee, Joseph Eggleston Johnston was born a son of Old Virginia. Lee was the son of “Light-Horse Harry” Lee of Revolutionary War fame, and Johnston the seventh child of Peter Johnston, who had fought under one of Light-Horse Harry’s officers, Major Joseph Eggleston, during the revolution. The boy was born on February 3, 1807, in Longwood House, the seat of Peter Johnston’s Cherry Grove plantation near Farmville.

A prominent planter and a judge, the husband of Mary Valentine Wood Johnston—herself the niece of Patrick (“Give me liberty or give me death”) Henry-Peter Johnston possessed more than enough social prestige and political clout to obtain a nomination for his son’s entry into the U.S. Military Academy in 1825. The young man enrolled, having been given the best of the kind of preparation Old Virginia plantation life could provide: plenty of manly outdoor activity, including hunting (which developed horsemanship and marksmanship), a sense of tradition and stewardship, and a combination of home schooling and lessons at Abingdon Academy that were both elegantly steeped in the classics. Young Joe Johnston’s classmate Robert E. Lee beat him academically at West Point, placing second in the forty-six-member Class of 1829 while Johnston came in at thirteen, but his showing was sufficiently respectable to get him an appointment as second lieutenant in Company C of the 4th U.S. Artillery. And, once in the army, Johnston’s rise was faster than Lee’s. Promoted to brigadier general in 1860, he earned the distinction of being the first West Point graduate to make general officer.

UPRISINGS

In 1830, Second Lieutenant Johnston was assigned, with Company C, as a coastal artillerist to garrison duty at Fort Columbus, Governors Island, New York. Here he passed an uneventful year before transferring, in August 1831, to Fort Monroe, in southeastern Virginia. He and his company were assigned to reinforce the garrison so that it could resist what was being called Nat Turner’s Rebellion.

Just before sunup on August 22, a slave preacher named Nat Turner led other slaves in an uprising against their master, Joseph Travis, then fanned out into Southampton County, killing every white person unfortunate enough to cross their path. (Among those who narrowly escaped the rampage was fifteen-year-old George Henry Thomas, a Virginian who would fight steadfastly for the Union at Chickamauga, Gettysburg, and elsewhere.) By the time Johnston and Company C arrived at Fort Monroe, Turner had been captured and executed, but his “rebellion” had been the realization of every slave owner’s nightmare. Although his family owned slaves, Johnston professed a moral revulsion to slavery, yet he was retained with the rest of Company C at Fort Monroe largely to ensure that any further uprising could be quickly contained and suppressed. The assignment, in any event, proved to be a pleasant interlude, especially since he was reunited with Lee, with whom he renewed and strengthened the friendship begun at West Point.

In May 1832, Johnston and his company were sent to Illinois, where they were committed to service in the Black Hawk War. As in the case of Nat Turner’s rampage, the army was tasked with putting the lid on another “uprising,” this one led by a Sauk chief, Black Hawk, who refused to accept eviction from his tribe’s traditional hunting grounds east of the Mississippi River and had clashed violently with new settlers along its banks. Johnston was excited by the prospect of the mission, which put him under the command of fellow Virginian Major General Winfield Scott, but neither Johnston nor anyone else in Scott’s command ever faced Black Hawk and his warriors in battle. The entire force was swept by cholera, which killed about half of Scott’s thousand-man command by the time it had gotten as far as Chicago. With only about two hundred “effectives,” including Johnston, Scott pressed on to the Mississippi River, only to learn that Black Hawk and his band had been defeated at the Battle of Bad Axe in August. Having traveled some two thousand miles, barely escaping dread disease, Johnston returned to Fort Monroe.

He remained in this pleasant, placid service until 1836, when General Scott personally requested his service on his staff as he fought the Second Seminole War (1835–1842) in Florida. There were heated skirmishes—Johnston’s first taste of combat—but most of the campaign consisted of futile tramps through miserable swampland in pursuit of an ever elusive enemy.

CIVILIAN INTERLUDE

In 1837, a treaty was signed with the Seminoles, who agreed to withdraw from their ancestral homes in Florida and resettle in Indian Country (modern Oklahoma and parts of adjacent states). With this, the fighting ended, and Johnston, seeing little future in the peacetime military, resigned his commission in March to start a career as a civilian engineer.

His West Point training stood him in good stead as he studied civil engineering, and by the end of 1837, he was employed as a contract topographic engineer aboard a small U.S. Navy survey craft commanded by Lieutenant William Pope McArthur. The peace brought by the treaty with the Seminoles proved fleeting, and, on January 12, 1838, at Jupiter, Florida, Seminole warriors set upon Johnston and the survey party he led. In the exchange of fire that followed, Johnston would later claim to have accumulated some thirty bullet holes in his clothing, and one bullet deeply creased his scalp, excavating a scar he would carry for life. One sailor in the survey party later reported that the “coolness, courage, and judgment” Johnston “displayed at the most critical and trying emergency was the theme of praise with everyone who beheld him.” Indeed, Johnston seems to have been exhilarated by this close brush with violent death. Although he was earning far more as a civilian engineer than as a military officer, he immediately resolved to return to the army.

In April, Johnston traveled to Washington, D.C., where he was commissioned a first lieutenant of topographic engineers on July 7. On that very day, he received an additional brevet to captain in recognition of his valor—though as a civilian—at Jupiter.

In 1841, Johnston was assigned as an engineer on the Texas–United States boundary survey, then returned to the East as the head of a coastal survey. While surveying near Baltimore, he met Lydia McLane, the daughter of Louis McLane, who had been a congressman and a senator from Delaware and had served in Andrew Jackson’s Cabinet as secretary of the treasury and secretary of state. Although she was fifteen years his junior, Johnston courted her, and they married in July 1845.

U.S.-MEXICAN WAR, 1846–1848

At the outbreak of the war with Mexico in April 1846, Johnston wasted no time requesting a combat assignment. General Scott welcomed him to the engineer staff of his Southern Army, which was preparing for its spectacular amphibious landing at Veracruz and an overland march to Mexico City. His fellow engineer officers were P. G. T. Beauregard, George B. McClellan, and the ranking member, Robert E. Lee. Once the Veracruz campaign was under way, Scott assigned Johnston to command a regiment known by the Napoleonic name of voltigeurs (literally “vaulters,” called such in Napoleon’s armies because they were trained to vault onto the rump of cavalry horses and ride double with cavalrymen in order to move quickly on the battlefield). In Scott’s army, the voltigeurs were elite reconnaissance-skirmishers who operated far in advance of the main force. They were tasked with ascertaining enemy troop dispositions and, when possible, engaging and holding the enemy until the main force could arrive. In recognition of their elite status, they were issued special gray uniforms to distinguish them from blue-clad conventional troops.

In the opening phases of the Veracruz campaign, at the head of the voltigeurs, Johnston was wounded twice in combat but recovered in time to participate in the principal battles en route to Mexico City, including Contreras (August 19–20, 1847), Churubusco (August 20), Molino del Rey (September 8), and Chapultepec (September 12–13), where he was wounded by musket fire no fewer than three times as he led his men up the slope of this hill topped by a fortified “castle” on the outskirts of Mexico City. Having already been brevetted to lieutenant colonel for his earlier valor, Johnston was specially cited by General Scott as a “great soldier,” the general wryly adding that he had the “unfortunate knack of getting himself shot in nearly every engagement.”

THE FIRST GENERAL

His multiple woundings did nothing to sate Johnston’s appetite for violent combat, and when, after the war, he returned to military engineering, this time as chief topographical engineer of the Department of Texas from 1848 to 1853, he found the tedium at times intolerable. Seeking more action, he transferred from the engineers to the cavalry in 1855, only to ponder resigning his commission in 1857 as his friend McClellan had done.

But he stuck it out. In 1858, he was transferred to Washington, then served for a time in California, returning to Washington, where, in 1860, he was promoted to brigadier general and named Quartermaster General of the U.S. Army on June 28. His ambition was to use this new position, in which he was responsible for managing much of the military budget, as a springboard to becoming the senior officer of the entire army. With this ambition uppermost in his mind, he did his best to try to ignore the developing secession crisis. Whatever was happening throughout the South, he resolved to do his duty to the United States and its army as long as he wore the uniform. He was hardly what the press at the time called a “fire eater”—a vehement advocate of secession. He despised slavery, and he rejected the argument many Southerners were making, that the right to secede from the Union was implied by the Constitution. In any case, whether it was a right or not, he opposed secession. Yet he came to the conclusion, as did Robert E. Lee and other sons of Old Virginia, that Virginia was his “country” and that he owed his loyalty first and last to it. He determined that he would share the fate of his state, whatever it might be.

Winfield Scott, his old commanding officer, a fellow Virginian, begged Johnston to remain loyal to the U.S. Army. When he saw that he was not getting through, that Johnston did not intend to allow his army loyalty to trump his allegiance to Virginia, Scott turned to Lydia McLane Johnston, who was a Baltimorean, not a Virginian. When she explained to General Scott that her husband would never “stay in an army that is about to invade his native land,” Scott took a fallback position, asking her to persuade him to leave the U.S. Army if he must but not to join “theirs.” In fact, Lydia Johnston believed that Jefferson Davis would “ruin” her husband, but she knew it was hopeless to try to persuade him not to rally to the defense of his “country,” his Virginia. As soon as the state seceded on April 17, 1861, he presented his resignation to General Scott, leaving behind him in Washington virtually all that he owned, save for the sword his father had carried in the American Revolution.

HARPERS FERRY COMMAND, SPRING 1861

Johnston arrived in Richmond on April 25 and called on Governor John Letcher to offer his services. Letcher told him that Robert E. Lee had arrived just four days earlier, at which time he appointed him commander of the state’s troops. After quickly consulting Lee, he offered Johnston command of state troops in and around Richmond. It was, Johnston recognized, a vital assignment, since Richmond, though not yet the capital of the Confederacy, was the capital of the South’s principal state and a key industrial and transportation center. As such, it was sure to be a prime target for Union attack. What is more, the city’s defenses were chaotic, and the situation cried out for someone to take charge. Johnston possessed the powerful command presence required to pull everyone into line.

While he threw himself into the work of military organization in Richmond, Johnston waited for the results of the Virginia Convention, which would decide on the final membership of the state army’s officer corps. Two weeks after his arrival in Richmond, Johnston was disappointed to learn that the convention had decided that Lee would be the only major general. When Letcher rushed to offer Johnston an appointment as brigadier general, he turned it down. Although he had left the U.S. Army to defend his home state, he now offered his services to the Provisional Confederate Army. It was not a decision based on Confederate nationalism but on a perceived command opportunity. Although the Confederate army offered nothing higher than the brigadier rank, Johnston understood that the Congress was about to pass a resolution elevating all brigadiers to full generals. He accepted the lower rank with the understanding that it would soon be raised.

After Johnston was formally commissioned on May 14, President Davis dispatched him to relieve Thomas J. Jackson as commanding officer at Harpers Ferry. Fifty-four-year-old Joseph E. Johnston was a distinguished and distinguished-looking officer, famed for combining valor with calm dignity and a compelling, charismatic personal presence. Davis hoped that he was just the man to work miracles at Harpers Ferry, but the president was about to learn that Johnston was not in the miracle business. Two days after arriving at his new command, he sent Davis a message declaring his opinion that Harpers Ferry could not be held against an enemy attack, at least not with the relatively small force he had available.

It was hardly what Davis or the Congress wanted to hear.

Johnston’s recommendation was to pull back from Harpers Ferry—let the Union have it—and instead use the freed-up resources to defend the Shenandoah Valley whenever and wherever required. Without a shot having been fired, Johnston was already proposing retreat. It rankled. However, in the end, Davis and his War Department agreed to allow him to pull back as far as Winchester, which he did behind a skillfully deployed cavalry screen that prevented Union forces from seeing where he had gone.

The maneuver would prove emblematic of Johnston’s strategic thinking. It would also ignite a debate about his fitness for command that would endure throughout the war.

For traditional military thinkers, like Davis, nothing was more important than holding and defending territory. Johnston, in contrast, believed that preserving the ability of an army to maneuver preserved its ability to fight, to do damage to the enemy army. Instead of tying down an army to a particular place, Johnston was willing to trade territory for maneuverability. From the beginning, he believed that defeating the Union states in straight-up warfare was impossible. The North had more people, more industry, more money. If, however, the South could stay in the fight, bleeding the North, the Confederacy just might outlast the Union will to continue the war. It was the lesson of the American Revolution, his father’s war. General Washington had well known that the puny Continental Army could not hope to defeat the military forces of the British nation, but if it could stay in the fight, it stood a chance of stretching the war will of British people and politicians just beyond the breaking point.

The question was this: Did Johnston’s vision of the nature of the Civil War demonstrate a truly advanced grasp of big-picture strategy? Or was he just insufficiently aggressive to defend the “sacred soil” of the Confederacy and bring the fight to the enemy?