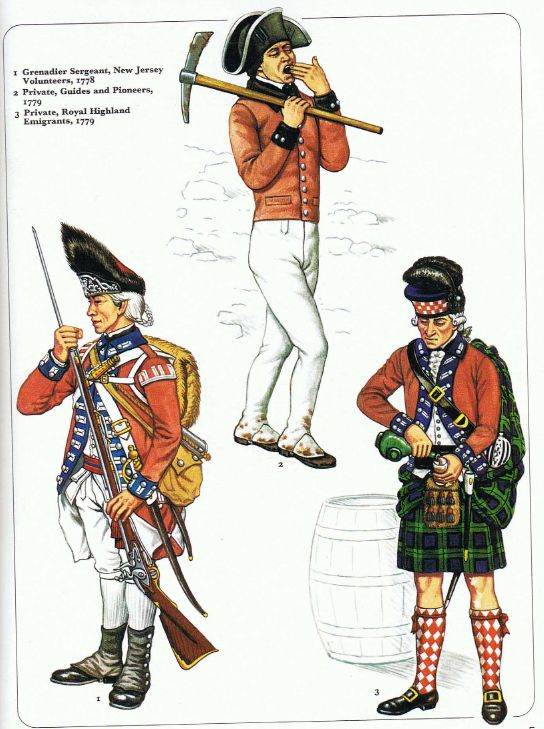

British Loyalist Troops; L to R Grenadier Sergeant, New Jesey Volunteers 1778, Private Guides and Pioneers 1779 & Private Royal Highland Emigrants 1779.

British; Loyalist Infantry L to R Privat, Royal Garrison Regiment 1783, Light Infantryman, Loyal American regiment 1782 & Private 3rd Battalion Delancy’s Brigade 1783.

British; Loyalist Troops L to R Officer British Legion 1781,Officer King’s American Dragoons 1782 & Fifer New York Volunteers 1782.

British;Loyalist Troops, L to R; North Carolina Militiaman 1775, Private The King’s Royal Regiment of New York 1777 & Private Loyal American Association 1775.

They are the forgotten ones; sharing the gloomy penumbra of history with impoverished White Russian aristos working as waiters in Paris in the 1920s after the Bolshevik revolution, or once-wealthy, cultivated South Vietnamese government officials opening delis in Los Angeles and New York after their country fell. They have about them a sepia sadness, the corners curled and the colors faded. Who cares? They were the losers.

The traditional estimate of Loyalist strength (first proposed by John Adams) is that one-third of Americans were patriot, one-third pro-British, and the remaining third neutral or persuadable one way or the other. Some historians think this three-way split is “too simple, and too high for the king’s adherents”; while others consider it too low. Somewhere between the two lay a very considerable body of people for whom the patriot cause was the destruction of the known, true, ordered, and trusted world, from which, at war’s end, over 80,000 of their persuasion would be banished.

There were two kinds of Loyalist. Claude Van Tyne in his classic, Loyalists in the American Revolution (1902), one of the first books devoted to their history, had no doubt who one kind was: “They were the prosperous and contented men, the men without a grievance…Men do not rebel to rid themselves of prosperity.” And for him they were Loyalism. But his description is by no means true of many, if not most. The other kind, particularly in the Carolinas and Georgia, were backcountrymen, mainly Celtic Scots immigrants (as against the predominantly Protestant Scotch-Irish), and mainly poor. They nursed bitter grievances (particularly against the Whiggish plantation society of the tidewater) that would, as the war progressed, work themselves out in a bloody civil war of startling savagery.

The wealthier Loyalist came predominantly from the middle colonies, particularly New York and New Jersey, which were the strongholds of Loyalism during the revolution. Those two colonies alone represented as much as 50 percent of American Loyalism, a fact reflected by Tom Paine’s outburst in the first issue of his broadsheet “The American Crisis” of 10 December 1776: “Why is it that the enemy hath left the New-England provinces, and made these middle ones the seat of war? The answer is easy: New-England is not infested with Tories, and we are.”

This particular strain is usually described as passive, overdependent on its British protectors, lacking in initiative, hesitant, crippled by its own gentility, and always a few fatal steps behind its better organized, more energized, more determined patriot enemy. They may have been relatively wealthier, but they were not effete grandees. When Massachusetts passed its Act of Banishment in 1778, the occupations of the 300 or so Loyalists slated spanned a broad gamut. A third were merchants, lawyers and other professionals, and “gentlemen”; another third were farmers; and the rest were artisans, laborers, and small shopkeepers. When over 1,000 Loyalists fled Boston with General Howe, the majority were middle-and lower-class. Two hundred and twenty-five were government officials, Anglican clergy, and large farmers; but 382 were small farmers, traders, and “mechanics.” Another 213 were merchants, and 200 unspecified.

Nor should we assume that Loyalists were somehow more “English” in their background. In fact, the crucible of the revolution was in the most “English” of the colonies (Massachusetts and Virginia), and it was here that Loyalism was relatively weak (only about one-tenth of Tories were in the Northeast). In fact, perhaps the most militarily active strain was far removed from genteel “Englishness.” The southern strand (approximately one-third of all Loyalists), with its Celtic impetuosity, its clannishness, its yearning for the heroic to the point of foolhardiness, rose up early in the war and was cut down almost as precipitately. On 27 February 1776 a Loyalist force of about 1,600, of whom 1,300 were Highland Scots under the command of Brigadier General Donald McDonald, their vanguard swordsmen led by Captains John Campbell and Alexander McCloud, charged across the bridge at Moore’s Creek, North Carolina, to attack 1,000 patriots dug in on the opposite bank. The Highland broadswords were met by concentrated musketry and artillery. Campbell, McCloud, and 40 of their men were killed; 850 were captured. The patriots lost one man killed and one wounded. A tribal style of war fighting, no matter how passionate, could not alter the cool mathematical logic of volleyed muskets and artillery.

Loyalism was a siren call for the British. They were constantly bending their strategy to conform to the chimera of Loyalist support that was assumed to be there but somehow never materialized. Howe’s Philadelphia campaign and Burgoyne’s invasion from Canada, as well as the British strategy in the South, were based on the assumption that large numbers of Loyalists would rise in support, if only sufficiently encouraged and protected, as many people—influential and knowledgeable people—whispered seductively. Ambrose Serle was among them. He had been an undersecretary to Lord Dartmouth when Dartmouth was secretary of state for the colonies between 1772 and 1775, and had come to America as Admiral Lord Howe’s secretary. Reporting on the situation in Pennsylvania in May 1778, he confidently reported Loyalist hopes: “Had some Conversation with Mr. Andw Allen. His most material Remark was…that five Sixths of the Province were against the Rebels, our Army had only to drive off Washington & to put arms into the Hands of the well-affected, and the Chain of Rebellion would be broken; especially if we restored the Province to the King’s Peace…That this wd affect all the Southern Colonies; & that then the Northern Colonies could not long stand out.”

In the South, James Simpson, the attorney general of South Carolina, reported in August 1779 to General Clinton and Secretary of State for the Colonies Lord George Germain: “I am of opinion, whenever the King’s Troops move to Carolina, they will be assisted, by very considerable numbers of the inhabitants, that if the respectable force proposed, moves thither early in the fall, the reduction of the country without risk or much opposition, will be the consequence.” Perhaps the most powerful voice in the British ear was that of William Knox, a wealthy Georgia landowner and sometime member of the Georgia Council, who had come to England in 1761 as agent for the state and had become undersecretary in the American Department. In his opinion Britain should cast off the insurgent northern colonies completely and re-form its empire in the South.

Broadly speaking, there were two main ways in which a Loyalist could serve the Crown in arms: in provincial regiments or in the militia. During the first years of the war Britain preferred, primarily for reasons of economy, to encourage Loyalists to raise their own regiments through a system known as “raising for rank.” It was, in essence, an entrepreneurial activity by which a prominent citizen set himself up as a recruiting agent (bearing most of the recruiting expenses) and prospective colonel of his regiment. For the British the system had some distinct advantages. It was cheap. Apart from shouldering the recruiting expenses, the recruiting officer was eligible for pay only when he had raised 75 percent of his regiment, and the officers of the regiment did not qualify for permanent rank with the British army or go on to half pay if the regiment was downsized or disbanded. At first, instead of a money bounty, each private soldier was given a royal grant of 50 acres while NCOs received 200 acres. Unlike the regular army, Loyalist regiments had no provision for medical care, and wounded officers did not receive invalid pay. And to underline their inferiority, if Loyalist field officers served with a regular British regiment, they were demoted to the most junior rank of the grade below their provincial grade.

As the pressure of the war bore down on resources, Britain was forced to pay more attention to the Loyalists as a military resource. In November 1776 Howe had asked Germain for 15,000 reinforcements, a number that horrified him. He might be able to muster perhaps half that, he thought. There would have to be more reliance on American manpower, and this requirement, to an important extent, dictated British strategy for the rest of the war. Howe’s 1777 invasion of Pennsylvania and the capture of Philadelphia, a stronghold of Loyalism—dismissed by most historians as strategically pointless and simply another indication of British dim-wittedness—makes more sense when it is seen in the light of the growing importance of hitching the Loyalist draft horse to the royal wagon. The load was becoming too heavy for the regular army to haul alone. As Howe explained in a rationale for his Philadelphia strategy, “The opinions of people being much changed in Pennsylvania, and their minds in general, from the late progress of the army, disposed to peace, in which sentiment they would be confirmed, by our getting possession of Philadelphia.”

Most of the important provincial regiments were raised following the fall of New York in September 1776. They included Oliver De Lancey’s brigade from New York; Robert Rogers’s Queen’s Rangers; Cortland Skinner’s New Jersey Volunteers (“Skinner’s Greens”); Sir John Johnson’s Royal Greens; Beverly Robinson’s Loyal American Regiment; and the New York Volunteers from Nova Scotia. In the winter of 1776 and spring of 1777, more important units were added, including Edmund Fanning’s King’s American Regiment from New York; John Coffin’s King’s Orange Rangers, a mounted rifle regiment from New York; Monteforte Brown’s Prince of Wales American Regiment, composed largely of Connecticut men; William Allen’s Pennsylvania Loyalists, who could boast Sir William Howe himself as their colonel; and James Chalmers’s Maryland Loyalists. Although almost eighty Loyalist regiments were raised over the course of the war (including black corps like the Jamaica Rangers, which was established in the summer of 1779 and had about 800 men of all ranks) and an estimated 15,000 men served at some time, it was those of 1776–77 who formed the backbone of the provincial service and within whose ranks two-thirds of all Loyalist troops would serve.