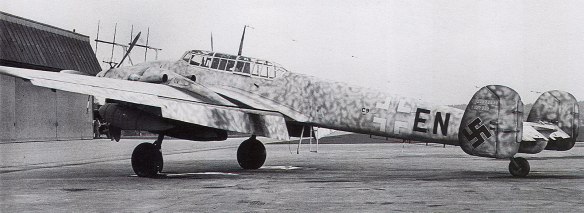

Johnen’s Bf-110 G-4 at Dubendorf.

In the dark skies over southern Germany on the night of April 28, 1944, a fierce shoot-out erupted when several squadrons of Luftwaffe fighter planes pounced on a British Royal Air Force bomber stream. During the confused battle, a three-seat Me-110 fighter, piloted by Leutnant Wilhelm Johnen, strayed into the airspace of neutral Switzerland.

Swiss antiaircraft-gun crews at Dübendorf Air Base bathed the German plane with powerful searchlight beams; then they fired red and green flares, signals for it to land. The plane approached the runway, and the searchlights were extinguished. Suddenly the Me-110 gained speed as if to escape, and the searchlight beams again caught the aircraft. The dazzling glare temporarily blinded Johnen and forced him to land.

Moments after the Me-110 rolled to a halt and the pilot shut off the engine, there was a tapping on the cockpit. A voice in German told the crew, “Please get out. You are in Switzerland. You are interned.” Glancing around, the Luftwaffe men saw that they were surrounded by twenty Swiss soldiers holding weapons aimed at the airplane.

Leutnant Johnen and his two crewmen promptly realized that they would have to take quick action to destroy secret devices on the Messerschmitt. The plane was equipped with the new night-flying radar, the Lichtenstein SN-2, which could track U.S. and British bombers from a distance in excess of four miles.

Also on board was an important new weapon that the Germans had given the nickname Slanted Music. It was a pair of top-mounted cannon that could fire directly upward and was designed to attack the vulnerable underside of Allied bombers.

Perhaps even more devastating to the German war effort should it fall into the hands of Allied intelligence was a set of top-flight Luftwaffe code books. Joachim Kamprath, the radio operator, had violated strict orders and brought the codes with him.

Before heeding the order to emerge from the Me-110, Kamprath tried futilely to badly damage the radar by kicking it. Paul Mahle, who manned the twin guns that fired upward, tried desperately, but failed to destroy them.

The tapping on the cockpit grew more insistent, so the Germans quickly stashed the secret code books into the pockets of their flight suits and climbed down onto the tarmac. After smoking a cigarette and chatting with the affable Swiss soldiers, Paul Mahle, the gunner, said he had to get back into the plane to retrieve some personal items. Without waiting for an approval, he scrambled into the cockpit.

Several Swiss soldiers were right on his heels, and they pulled the struggling gunner by one leg as he tried to reach a switch that would have touched off a delayed-action explosive device and blown up the aircraft.

Then the three interned men the Swiss didn’t regard them as captives were escorted to the air base canteen, where they were given food and wine. After the Germans excused themselves to go to the men’s room, two Swiss soldiers followed, saw them flushing pages from the secret code books down the toilet, and snatched the remainder of the sheets from them.

Twenty-four hours later, the German high command in Berlin erupted in near-panic. Swiss officials refused to return the Me-110 that had violated their tiny nation’s airspace. Berlin feared that the secret equipment and the code books might be slipped to Allied intelligence by the Swiss.

Suspecting that the three Luftwaffe men had committed treason, the Gestapo immediately arrested their families. Reichsführer Heinrich Himmler, once a chicken farmer and now Gestapo chief and head of the elite Schutzstaffel (SS), probed the possibility of using Nazi espionage agents already in Switzerland to murder the three downed German airmen.

At his battle headquarters at Wolfsschanze behind the Russian Front, Adolf Hitler flew into a rage on being told of the Swiss episode by his longtime trusted chief of staff, Generaloberst (four-star general) Alfred Jodl. However, the Führer rejected Himmler’s murder plan and also a scheme by the Luftwaffe chief, rotund Reichsmarschall Hermann Goering, to heavily bomb Dübendorf Air Base.

Instead, Hitler sent for one of his favorites, SS Sturmbannführer (Major) Otto Skorzeny, a folk hero on the German home front, a sinister figure known as “Scarface Otto” to the Allies. A burly 6 feet, 3 inches tall and weighing 250 pounds, the “commando extraordinary,” as he came to be known in the Third Reich, was handed a seemingly impossible assignment: locate and destroy the Me-110 being held by the Swiss.

The mission would require exceptional stealth, cunning, and courage, traits that Skorzeny had in abundance. As an engineering student in his native Vienna, he had fought fifteen of the ritual saber duels popular among some Teutonic types. In one encounter, young Skorzeny’s left cheek to the tip of his jaw had been laid open. It was sewn up on the spot without anesthetic and the duel resumed.

After joining the SS in 1940, Oberleutnant (First Lieutenant) Skorzeny fought in the Balkans and later in Russia, from where he was invalided home with severe head wounds. He commanded a desk until late July 1943, when the Führer assigned him the daunting task of rescuing Hitler’s crony Benito Mussolini, who had been in almost absolute control of Italy for twenty-one years.

Mussolini had been taken prisoner by Italian partisans after having been booted out of his office by shy, diminutive King Victor Emmanuel III, and was being held prisoner in a peacetime tourist hotel on a towering peak in the Appenines known as Gran Sasso. After spending two weeks prowling around Italy in civilian clothes, Skorzeny had discovered where Mussolini was incarcerated.

On September 12 Skorzeny and a handful of Fallschirmjäger (paratroopers) swooped down on Gran Sasso in gliders, snatched the deposed dictator from under the noses of more than two hundred Italian guards, and bundled the famous prisoner into a light Storch aircraft that had just made a dangerous landing near the hotel.

The bulky Skorzeny wriggled into the little plane designed to carry two passengers and, along with Mussolini and a Luftwaffe pilot, Hauptman (Captain) Heinrich Gerlach, lifted off from a short, boulder-strewn plateau. On reaching the edge of the plateau, the Storch plunged downward into a yawning valley and Gerlach was able to right the aircraft just before it crashed. Flying at treetop level, the pilot set a course for Rome, which was still in German hands.

Now Otto Skorzeny had been given an equally “impossible” task-finding and blowing up the Me-110. As he had done in his search for Mussolini’s whereabouts, Skorzeny, a conspicuous figure because of his great bulk and ugly dueling scar, put on civilian clothes and slipped across the border into Switzerland at night.

Skorzeny ambled around the perimeter of Dübendorf Air Base, seeking some sign of the German aircraft, asking questions of natives living nearly and of civilian employees as they left the facility. Swiss authorities had moved the Me-110 deep within the mountainous country, the commando learned. Finding it would be akin to discovering the proverbial needle in a haystack. So Skorzeny, for one of the few times in his life, had to admit defeat.

Now behind-the-scenes diplomatic maneuvering took place, and a strange deal was worked out between Nazi Germany and Switzerland. On the morning of May 17, 1944, Hitler’s military attaché watched intently as the Messerschmitt, which had been brought back to Dübendorf, with its secret equipment, was doused with gasoline and burned to a crisp.

For its part in the arrangement, the Swiss government was permitted to purchase from Germany twelve high-performance Me-109G fighter planes, a major concession since the seriously depleted Luftwaffe needed every available aircraft to combat the almost daily and nightly raids by British and U.S. bombers against targets in the German homeland.

As a component of the secret agreement, Leutnant Wilhelm Johnen, radar operator Joachim Kamprath, and gunner Paul Mahle were released from custody and returned to Germany. The three airmen were held blameless once the true details of the Dübendorf episode became known to German intelligence, and their families were released from prison.

Perhaps the airmen’s fate would have been different had the Gestapo learned about the Luftwaffe secret code books, most of which presumably were in the hands of Swiss authorities or maybe being scrutinized by U.S. and British intelligence.