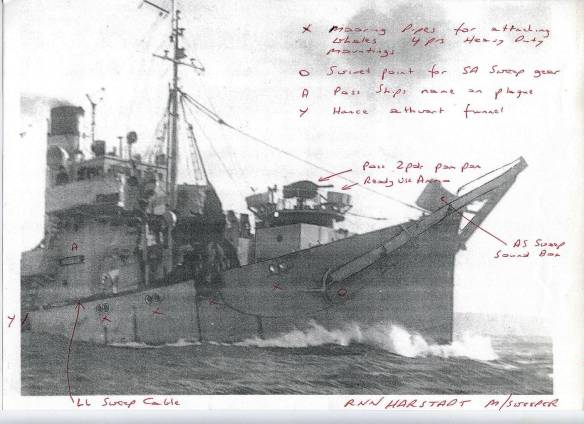

The ex-whaler Harstad. HMT Harstad 1943. The auxiliary minesweeper was torpedoed and sunk in Lyme Bay (50°24′21″N 3°01′41″W) by Kriegsmarine E-boats with the loss of 22 of her 23 crew.

The Strike Wings of Coastal Command now had a viable anti-shipping weapon, and in the months to come they would put it to devastating use. Meanwhile, the spring of 1943 had seen a surge of naval activity in the area of the English Channel. On 27 February, the 5th S-boat Flotilla carried out a particularly audacious sortie, four craft – the S65, S68, S81 and S85 – penetrating into Lyme Bay and attacking a convoy that had assembled there. In a matter of minutes, they torpedoed and sank the freighter Moldavia (4,858 tons), the Tank Landing Craft LCT 381 (625 tons) and two escort vessels, the armed trawler Lord Hailsham and the whaler Harstad. The S-boats retired without loss. On the next night, an attempt to attack a southbound German convoy by four Coastal Force MGBs was broken up by accurate defensive fire from seven escort vessels, MGB 79 being sunk. (The convoy had earlier lost the patrol boat V 1318, which struck a mine off Ijmuiden.)

A mine also accounted for Schnellboote S70, lost during a sortie by the 2nd, 4th and 6th S-boat Flotillas into the area of Lowestoft and Great Yarmouth on the night of 4/5 March 1943. The enemy craft were driven off by the destroyers Windsor and Southdown and the corvette Sheldrake, and the following morning they also lost the S75, attacked and sunk off Ijmuiden by Spitfires and Typhoons. In addition to this sortie, S-boats attempted to attack a convoy off Start Point, but this was frustrated by accurate fire from the Polish destroyer Krakowiak. The Schnellboote were again active on the night of 7/8 March, attempting to attack shipping near the Sunk Lightship, but the raid was broken up by the destroyer Mackay and four MGBs. Two S-boats collided while taking evasive action; one of them, S119, was sunk by MGB20 after her crew had been taken off by S114 the other craft involved in the accident.

The middle of April saw a flurry of intense naval action, beginning on the night of 12/13 when a German convoy was attacked by MGBs 74, 75, 111 and 112, both sides sustaining slight damage. On the next night, the 5th Schnellboote Flotilla, led by its redoubtable commander, Kapitänleutnant Klug, scored a resounding success off the Lizard Head in an attack on Convoy PW323, comprising six merchant vessels, the Hunt class destroyers Eskdale and Glaisdale, and five armed trawlers. Four Schnellboote – S90, S112, S116 and S121 – broke through the defensive screen and S90 hit Eskdale with two torpedoes, bringing her to a standstill. She was later sunk by S65 and S112. Meanwhile, the 1,742-ton freighter Stanlake was torpedoed by S121 and finished off by the S90 and S82.

All four S-boats returned to their base without loss.

There was a better outcome for the British on the night of 27/28 April, when the destroyers Albrighton and Goathland attacked a German convoy of two medium-sized merchantmen, escorted by two trawlers and a minesweeper, 60 miles north-north-east of Ushant, off Ile de Bas. Both freighters were hit by torpedoes and heavily damaged, though neither was sunk, but one of the escorting trawlers – UJ 1402 – was destroyed by gunfire. HMS Albrighton became involved in a 90-minute close quarter gun battle with some S-boats that arrived on the scene and received damage that put her out of action until the end of May.

With the advent of the light nights of summer as in the previous year, the excursions of the S-boats into British waters became less frequent, and minelaying by aircraft and destroyers intensified. On the night of 2/3 May, Dornier 217s of KG 2 laid mines in the estuaries of the Humber and Thames and also on the convoy route between Dover and the Thames Estuary, and on 11/12 May 36 aircraft sowed mines on the Humber– Thames convoy route. Six aircraft were lost, mainly to Mosquito night-fighters. On the following night, craft of the 1st, 7th and 9th Minesweeper Flotillas, carrying out Operation Stemmbogen – which involved sowing mines in the southern part of the North Sea, west of the Hook of Holland – were attacked by four MTBs, which hit and sank the M8 with two torpedoes. A further major German minelaying operation was undertaken during the last week in May by S-boats of the 2nd, 4th, 5th and 6th Flotillas, which laid mines between Cherbourg and Peter Port, the Isle of Wight and Portland, and in Lyme Bay. The latter objective was mined three times again in June, when mines were also sown off Start Point. In all, the Schnellboote laid 321 mines in the course of 77 sorties. The first week in July saw another German ‘harbour-hopping’ operation, with the Elbing class destroyers T24 and T25 moving westwards through the Channel from the North Sea. During the move they were unsuccesfully shelled by the Dover gun batteries, attacked off Dunkirk by three MTBs and attacked in Boulogne by Typhoons. On the night of 9/10 July they joined five minesweepers in escorting a convoy, which was attacked by the destroyers Melbreak, Wensleydale and Glaisdale. The minesweeper M135 was sunk in the ensuing battle, but HMS Melbreak was badly damaged.

During this period, the main opportunities for engaging the Schnellboote came when the latter were detected moving from port to port. On 24/25 July, for example, S68 and S77, en route from Boulogne to Ostend, were attacked by British MTBs and MGBs, which sank S77 north of Dunkirk, while on 11 August craft of the 4th and 5th S-boat Flotillas, transferring to L’Abervach in readiness for a sortie against Plymouth Sound, were attached by Typhoons. S121 was sunk, S117 badly damaged and four others slightly damaged out of the seven-boat force.

There was a resurgence of German minelaying activities in October 1943, with the return of longer hours of darkness, and an increase in actions against convoys. It was during one such action, on 23 October, that the Royal Navy suffered a further severe loss.

For some time, Allied Intelligence had been aware that a blockade runner, a fast, ultra-modern cargo vessel of 10,000 tons named Milnsterland, had been heading back to Germany from Japan with a cargo of rubber and strategic metals, both vital to the German war effort. By a series of incredible circumstances, she had evaded Allied air and naval patrols on the homeward run and had reached Brest, where she was attacked by B-25 Mitchell medium bombers without success. Following the usual harbour-hopping procedure, Münsterland then moved on to Cherbourg, where she was attacked by the Typhoons and Whirlwinds of Nos. 183 and 263 Squadrons, both operating from Warmwell.

Meanwhile, the Royal Navy had also tried to intercept her, with unfortunate results, during the passage from Brest to Cherbourg on the night of 22/23 October. The British naval force comprised the light cruiser Charybdis, the Fleet destroyers Grenville and Rocket and the Hunt class destroyers Limbourne, Talybont, Wensleydale and Stevenstone. Münsterland was escorted by six minesweepers of the 2nd Flotilla, two new radar-equipped patrol vessels, V718 and V719, and five Elbing class destroyers providing an outer screen.

Charybdis made radar contact with the enemy force off Ushant at 0130 on 23 October. Her accompanying destroyers also made contact at about the same time, but no information as to the probable size and composition of the enemy force was exchanged.

By this time the Germans were aware of the British warships approaching to intercept them, and the outer destroyer screen obtained a visual sighting on Charybdis, which was seen turning to port. The leading destroyer, T23, immediately launched a full salvo of six torpedoes at her. At 0145 the British cruiser opened fire with starshell, and her lookouts at once sighted two torpedo tracks heading towards her port side. One, or possibly both, torpedoes struck home and Charybdis came to a halt, listing heavily to port.

By now the other German destroyers had joined in the action, firing several more torpedoes at the British destroyers coming up behind the stricken cruiser. Charybdis was hit again, while a torpedo launched by T22 struck HMS Limbourne. The cruiser sank very quickly, and despite determined attempts to save her, Limbourne was also beyond redemption. She was sunk by torpedoes from Talybont and Rocket, which returned to Plymouth with the other surviving destroyers.

The action had cost two warships, the lives of 581 officers and ratings, and had achieved nothing. The enemy convoy escaped unharmed, and the next morning air reconnaissance revealed Münsterland at Cherbourg and the five Elbings at St Malo. As mentioned earlier, the freighter was subsequently attacked by Typhoons and Whirlwinds through flak described by one pilot as ‘a horizontal rainstorm painted red’. Two Whirlwinds out of 12 were shot down and two more crashed on return to base, and the Typhoons lost three aircraft out of eight, but the Münsterland was damaged and her progress delayed. She eventually reached Boulogne, where she was attacked early in January 1944 by rocket-firing Typhoons of No. 198 Squadron and damaged again. This time, although five aircraft were hit, all made it back to base, two crash-landed at Manston. The Münsterland story finally came to an end on 20 January, when, after leaving Boulogne, she ran aground in fog west of Cap Blanc Nez and was shelled to pieces by the Dover guns. The Typhoon pilots of Nos. 198 and 609 Squadrons, arriving when the fog lifted, relieved their frustration by firing their rockets into what was left of the superstructure.

In the closing weeks of 1943, the tactical air forces were assigned to the first of a lengthy series of attacks on a new threat that had been perceived across the Channel: the launching sites, then under construction in the Pas de Calais, for the V-1 flying bomb. With the heavy bombers of RAF Bomber Command and the USAAF preoccupied with the strategic air offensive against Germany, this new task fell to medium bombers and single-engined fighter-bombers, including the Hurricane IVs of Nos. 164 and 184 Squadron, as Jack Rose explains:

In the winter months of 1943–44, just before we re-equipped with Typhoons, we carried out a series of attacks on so-called NO-BALL (V-1) targets in northern France. We were then operating from Woodchurch, one of the airfields scattered over Romney Marsh speedily constructed of wire mesh on grass. My log book records attacks on numbered NO-BALL sites 40, 88, 28, 46, 81 etc and also on named sites at Montorquet, Bois Nigle, La Longueville and so on. We usually flew, again in fours, when the cloud conditions gave the maximum cover if needed. Photographs were always used for the final approach.

I can remember seeing an intelligence report at about this time in which damage to the NO-BALL sites was given in relation to the weight of bombs dropped by various types of aircraft. The categories were heavy bombers, medium bombers, and rocket firing aircraft. Although we had loads of only 480 lb (8 x 60 lb), the damage inflicted by our attacks per ton of ‘bombs’ dropped was, I suppose understandably, very much greater than the damage per ton dropped by the – mostly American – medium and heavy bombers.

Nevertheless, the damage inflicted by the Hurricanes of the two ground-attack squadrons was achieved at considerable cost; on one occasion, during an attack on a No-Ball site that cost Flight Lieutenant Ruffhead his life, three out of the four Hurricanes he was leading failed to return. Many of the most severe losses were sustained when the enemy defences were fully alerted – as, for example, when a section of Hurricanes made a faulty landfall and consequently had to make a longer approach to their target. Because of the losses, the Hurricanes were given a Spitfire escort whenever possible.

Woodchurch, the rocket-firing Hurricanes base during their costly anti-No-Ball sorties, was only one of many similar advanced landing grounds (ALGs) that had sprung up all over southern England, close to the Channel coast, during the year. For in 1943 Britain had been gradually turned into a vast arsenal, and strips such as these would soon enable the Allies to wield the weapons that were now being forged to hurl their armies across the Channel, and to establish secure foothold in occupied Europe.

Many of the ALGs that were refurbished in 1943 were originally so called ‘scatter’ fields, emergency landing strips created at the time of the Battle of Britain as insurance against the principal fighter airfield being made unserviceable by enemy bombing, which they sometimes were. With the battle won hundreds more sites were inspected south of a line from the Thames to the Severn to provide a springboard for the aircraft that would eventually spearhead an assault on the German-held coastline of Europe. The list was eventually shortened to 72, but such was the need for food-producing land that the airfield construction scheme was strongly opposed by the War Agricultural Executive Committee, and in the end only 25 proposals were accepted, of which 23 involved ALGs to be constructed along the Channel coast from Kent to Hampshire. Eleven of the new ALGs were allocated to the United States Army Air Forces, (USAAF) whose advance units had become operational in the United Kingdom in the summer of 1942. The original target date for the completion of the ALGs was March 1943, but construction was set back somewhat by a shortage of materials and, not least, by the English weather.

Hand-in-hand with the ALG construction programme went the formation of a so-called ‘Composite Group’ of fighter, fighter-bomber, light bomber and reconnaissance squadrons which, operating at first from the new forward airfields near the coast, would support an Allied expedition to France. On 1 June 1943, this formation was re-designated the Tactical Air Force (TAF), and with this the old Army Co-Operation Command became defunct. Later, the designation was again changed to Second Tactical Air Force, its role being to support the Anglo-Canadian Group of Armies. The American armies training for the invasion of Europe had their corresponding tactical air support in the form of the IX Tactical Air Command.

In November 1943 a large number of RAF squadrons were transferred from the various other commands to the Second TAF, which now comprised four groups. No. 83 and 84 Groups were to provide tactical support for the 1st Canadian and 2nd British Armies, No. 85 Group was to defend the Allied bridgehead across the Channel once it had been established, and the medium bombers Marauders, Mitchells, Mosquitoes and Bostons of No. 2 Group were to Strike at communications and supplies behind the enemy lines. There was also a Reconnaissance Wing and an Air Spotting Pool, and the massive task of furnishing air transport and supply fell to No. 38 Group. All these formations, together with the mighty power of the United States Ninth Air Force, were incorporated into the Allied Expeditionary Air Force, commanded by Air Marshal Sir Trafford Leigh-Mallory.

So, gradually, the machinery that would place a great body of men on the beaches of Normandy in the coming year was being fitted into place. But although the Allied armies were undergoing the type of training that would ensure no repetition of the Dieppe débâcle, and although the Allied air forces were reaching a pinnacle of strength of over five and a half thousand aircraft, enough to ensure complete air supremacy when the landings were achieved, there was still the physical problem of shipping the armies across the English Channel and of safeguarding them in passage; and only the Allied navies could achieve this twin objective.

In December 1943, as preparations for the great leap across the Channel gathered momentum, there was still a long way to go; and there was more than one major obstacle to be overcome.