Those who fought in the Western Desert and those who reported the fighting there devoted a good deal of effort to describing the setting. They noted the daytime heat and the nighttime cold, the swarming flies and the gritty, blowing sand, the spectacular sunsets and the star-filled night skies. As they groped for a proper descriptive image, the one they most often hit upon was to compare the desert to the ocean.

Often, nothing but the unbroken line of the horizon could be seen in any direction. Vehicles moved freely across this expanse like ships at sea. Men did not just drive in the desert, they navigated, getting where they wanted to go by using speedometer, map, and compass. The few landmarks were usually man-made: a heap of rocks or empty gasoline cans, a stone cistern for catching rainwater, a whitewashed Moslem mosque, a long procession of telephone poles. The only paved road was the coast road. Inland, vehicles followed rough, dusty tracks that avoided the worst of the rocky outcroppings and patches of soft sand.

From the shore of the Mediterranean, the Libyan Desert, or the Western Desert, as it was called in those days, climbs upward in a haphazard series of steps, or escarpments. In most places, these escarpments are too steep for trucks and even for tanks, so the few natural gaps, or passes, became important military objectives. The surface of the desert is largely underlaid with limestone; tracked vehicles, at least, could drive almost anywhere on it. Only well inland does the true desert of drifting sand dunes begin. Narrow, stony ravines, called wadies, look from the air like jagged cracks. Here and there lie large dish-like depressions known as deirs. Inland from the sea, rain falls only two or three times a year – and in some places, only once in two or three years.

A German general aptly described North Africa as a “tactician’s paradise and a quartermaster’s hell.” The long, narrow desert battlefield stretched over 1,400 miles from Tripoli on the west, the Axis’ major port, to Alexandria on the east, the Allies’ chief base. The Germans and the Italians on the one hand and the British on the other were willing to spend their blood and treasure to win this desolate strip of land simply because neither side could afford to let the other have it. For the British, the Western Desert was the buffer that protected the Suez Canal and the Middle Eastern oil fields, both of which the Axis powers wanted. In addition, whoever controlled the North African airfields was well ahead in the race to control the strategically vital Mediterranean.

As Marshal Graziani had ruefully noted, desert war imposed its own special rules. Rule number one was that armies brought with them everything they needed. There was no way to live off the country. As a result, the two most precious liquids were gasoline and water. For the British soldier, remarked a war correspondent, “The great problem in the mornings was to decide whether to make tea with the shaving water or to shave in the tea.” What was left of a man’s daily water ration (seldom more than a gallon) after drinking, cooking, bathing, and washing his clothes had to go into the radiator of his vehicle.

The second rule was the importance of complete mobility. In the desert, infantrymen did not march; they rode in trucks. The queen of battle was the tank. Closely related to mobility was rule number three: the need for speed. A fast-moving, quick-off-the-mark army, as General O’Connor’s Western Desert Force had proved, possessed an enormous edge, and a quick-thinking, energetic general could dominate an opponent who paused to gather up all the loose ends.

The final rule of desert warfare dealt with the nature of the battlefield itself. There were no industrial centers to capture, no captive populations to rule, no political considerations to clutter up tactics. It was a purely military struggle on an empty stage, and it was entirely possible to honor whatever “rules of the game” might still exist in a total war.

To meet the pressing needs in Greece and East Africa, General Wavell had left the Western Desert Force gravely weakened. “Next month or two will be anxious,” he cabled Prime Minister Churchill in March 1941, but he estimated that the enemy in Libya would not be strong enough to risk an attack before May. This, in fact, was precisely the timetable given in Hitler’s orders to General Rommel. The turn of events was to surprise Hitler as much as Wavell.

Erwin Rommel was a forty-nine-year-old professional soldier whose reckless bravery during World War I had brought him two wounds and the Pour le Mérite, Germany’s highest military decoration. Outspoken and blunt, Rommel lacked the arrogant polish of the Prussian aristocracy that supplied the German Army with so many of its officers. In the 1930s, a book he wrote stressing boldness in infantry tactics caught Adolf Hitler’s eye. In 1940, during the Battle of France, he led a panzer division with dash and brilliance. Hitler concluded that here was the man to come to the aid of Mussolini. The moment Rommel set foot in North Africa, the situation began to happen.

Hitler had promised Mussolini an “Afrika Korps” of two German divisions, one armored and one of motorized infantry. When the 5th Light Motorized Division – a self-contained force of infantry, armor, artillery, and antitank and antiaircraft guns – arrived at Tripoli in February 1941, Rommel ordered the ships unloaded through the night, ignoring the danger of the RAF bombing the lighted docks. He put his engineers to building dummy wooden tanks atop little Volkswagen staff cars to make the British think he was stronger than he was, and he hurried his advance units to El Agheila, the westernmost British outpost in Libya, to test the enemy’s strength.

The army that faced Rommel was not the same fast-moving, quick-thinking force that had chased Marshal Graziani out of Egypt. The Desert Rats of the 7th Armored Division, back in Egypt for rest and refitting, had been replaced by the newly arrived 2nd Armored Division, green and at half strength. The 6th Australian Infantry, victors at Bardia and Tobruk and Benghazi, was relieved by another Australian division, untrained and poorly equipped. Replacing O’Connor in command was Lieutenant General Philip Neame, a newcomer to the desert.

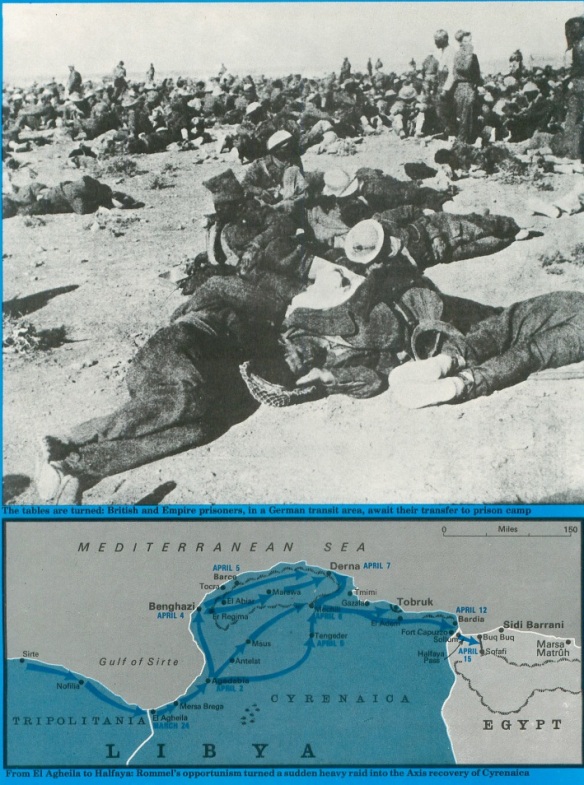

On March 24, 1941, the German advance guard drove the British out of El Agheila. A week later, Rommel launched a second attack. Sensing the weakness before him, he disregarded his orders. “It was a chance I could not resist,” he wrote. By April 2, Neame’s defenses were splintered. Orders went out to abandon Benghazi if necessary. Wavell commanded General O’Connor to fly at once to Cyrenaica to try to restore a defensive front.

There was little O’Connor could do, for Western Desert Force was rapidly falling apart. Communications broke down, orders were bungled, and troops went astray. An enormous supply dump containing most of the 2nd Armored’s gas was set afire by its guards when they thought the enemy was approaching; the “enemy” turned out to be a British patrol.

As O’Connor had done earlier in the year, Rommel took the desert shortcut across the base of the Cyrenaican “bulge.” He pushed his men relentlessly, flying from one column to another in his tiny Storch plane. When told that the vehicles needed servicing and repairs, he ordered his officers not to bother with such “trifles.” The 5th Light Division’s commander asked for a four-day halt to bring up ammunition and gasoline; Rommel had him empty all his trucks – leaving the division stranded immobile in the desert for twenty-four hours – and send them back to depots to bring up the needed supplies. An Italian general complained that he was being ordered into impassable terrain; Rommel drove ahead a dozen miles by himself to prove the path was clear.

Late on April 3, Rommel paused long enough to write his wife: “We’ve been attacking since the 31st with dazzling success. There’ll be consternation amongst our masters in Tripoli and Rome and perhaps in Berlin, too. I took the risk against all orders and instructions because the opportunity seemed favorable. . . . You will understand that I can’t sleep for happiness.” By April 6, most of the Cyrenaican bulge was in Axis hands. Benghazi had fallen, and the spread fingers of Rommel’s columns were reaching for Mechili, where the exhausted British were regrouping.

That night, a British staff car drove headlong into a German scouting force on one of the desert tracks north of Mechili. There was a brief exchange of gunfire, killing the British driver and a German motorcyclist. The staff car was surrounded, and the occupants were ordered to surrender. Out stepped generals Neame and O’Connor and Brigadier John Combe, whose Combeforce had slammed the door on the retreating Italians barely two months before. (So seriously did Wavell feel O’Connor’s loss that he tried – unsuccessfully – to exchange him for any six captured Italian generals that Mussolini’s high command cared to choose.)

The next day Mechili capitulated. The British streamed eastward. Most of the Australian infantry reached safety in the defenses of Tobruk, but the 2nd Armored Division was shattered; it never again appeared on the battle roles of the British Army. Seeking a quick victory, Rommel threw his troops at Tobruk. But his planning was too hurried and his men too exhausted, and the assault was repulsed. German armored forces bypassed the fortress and seized Bardia and Sallum, key points along the coastal escarpment. Cyrenaica had been regained, and once more the Axis were at the gates of Egypt.

April 1941 was a month of severe trial for Great Britain. Only the campaign against the Italians in East Africa went well. Officials in London sugar-coated the defeat in the Western Desert with such phrases as “a withdrawal to a battleground of our own choosing” and “part of a plan for an elastic defence,” but few Britons were fooled. On April 6, Hitler attacked Yugoslavia, whose capital, Belgrade, fell within a week. Greece, too, was invaded. The forces sent there at such cost by Wavell could not stem the Nazi tide, and by the end of the month, they had to be evacuated. The British island of Malta, key to control of the Mediterranean, was savagely pounded by the Luftwaffe. Oil-rich Iraq, east of Suez, was torn by an anti-British revolt, and there were signs that a similar uprising was brewing in Syria. In a grim mood, Churchill wrote President Franklin D. Roosevelt: “In this war, every post is a winning-post, and how many more are we going to lose?”

As usual, Churchill met trouble by bounding into action. Axis submarines, warships, and planes were so thick in the Mediterranean that British ships carrying supplies to the Middle East took the slow, 14,000-mile route around Africa and through the Red Sea to Egypt. Now, overriding the objections of his military advisers, Churchill ordered the Royal Navy to force a passage through the Mediterranean with a convoy of merchant ships carrying tanks to General Wavell.

The codename for his bold plan was Operation Tiger.

It would have comforted the prime minister to know that just then all was not serene in the Axis camp. Rommel was determined to press into Egypt and beyond as soon as he was re-supplied and the Tobruk thorn was removed from his flank. But his unexpected victories had embarrassed the German high command because it had not intended North Africa to be a major theater of war. General Franz Halder, chief of the German General Staff, complained in his diary that Rommel did not even submit proper reports; instead, “All day long he rushes about between his widely scattered units.” Something must be done to “head off this soldier gone stark mad,” Halder thought, or he would embroil Germany in a campaign beyond her resources.

Shrugging off his first repulse at Tobruk, Rommel searched for a soft spot in its defenses. Tobruk was important because of its harbor, the only one of any size between Alexandria and Benghazi. The desert around the small, whitewashed town was flat as a plate; the verdict of one observer was that it “must have been difficult to defend even in the days of bows and arrows.” Yet, before the war, the Italians had lavished tons of concrete and steel on its defenses.

A double row of strong points and trenches formed a semicircle thirty miles around the harbor. The British strengthened this line with barbed wire, tank traps, minefields, and a heavy concentration of artillery. The garrison, made up mostly of Australian infantry supported by a few tanks, was led by General Leslie Morshead. He and his Aussies were very determined. “There is to be no surrender and no retreat,” Morshead told his officers.

Rommel ordered three major assaults against the Australians, using a variety of tactics. But his forces were too weak, and the opposition too unwavering, to achieve a breakthrough. By May, he had to content himself with tightening the ring around the fortress while he waited impatiently for reinforcements.

The siege of Tobruk was to drag on for eight months, until the winter of 1941. It was a boring, bloody, dangerous stalemate for the men on both sides. They “went to ground” during the day, suffering the stifling heat and the swarming insects to avoid snipers’ bullets. Bombing and artillery fire took a steady toll. The desolate landscape, wrote a British war correspondent, was “littered with broken transport, burned-out tanks, and spent ammunition, as though some junk merchant had set up business on the surface of the moon.” Morshead’s garrison could be supplied only by ship and only at night, and British naval losses were heavy. But neither side would loosen its grip. To the British Commonwealth, Tobruk came to stand for stubborn courage in the face of adversity. To Rommel, Tobruk was a symbol of frustration. He vowed that the fortress would be his.

For General Wavell, events were rapidly reaching a climax. He moved his available forces across the vast chessboard of the Middle East – to put down revolts in Iraq and Syria, to gain final victory over the Italians in East Africa, to probe Rommel’s outposts on the Egyptian frontier, to counter (unsuccessfully) a massive assault on the island of Crete by German paratroopers. All the while a blizzard of telegrams from Churchill crying for action descended on Wavell’s Cairo headquarters.

On May 12, 1941, the Tiger convoy anchored at Alexandria, having lost only one ship in the Mediterranean passage and bringing Wavell 238 tanks. Churchill, who had risked so much to get these reinforcements to the Middle East, waited anxiously for his Tiger Cubs, as he called them, to go into action. Wavell replied that Operation Battleaxe was scheduled for June 15. He intended to use the new tanks to break Rommel’s shield at Sallum and Bardia and then advance seventy miles westward to lift the siege of Tobruk. The Desert Rats of the 7th Armored Division would spearhead the attack.

Battleaxe called for the 4th Indian Division, supported by infantry tanks, to capture Halfaya Pass, an important gap in the coastal escarpment near Sallum. The British armor would meanwhile swing around to the left beyond the Axis positions guarding Sallum and Bardia. Here, on the desert flank, Wavell saw the decisive tank battle taking place.

On the appointed morning, eighteen Matildas waddled toward Halfaya Pass, followed by Indian infantrymen in trucks. Before the tanks were close enough to fire effectively, they were hit by a hail of armor-piercing shells. Eleven of the twelve leading Matildas stopped dead, some in flames, others with gun turrets blown completely off their hulls. Four others behind them withdrew, blundered into a mine field, and had tracks blown off. Later the same day, far out on the desert flank, a column of British cruiser tanks met the same devastating fire from a German strong point.

Thus were British armored forces introduced to the German eighty-eight-millimeter gun, one of the best artillery pieces of World War II. A dual-purpose antiaircraft and antitank gun, the long-barreled eighty-eight was accurate and fast firing, and its twenty-one-pound shell had tremendous hitting power; at a range of well over a mile, it could kill even the most heavily armored tank with a single shot. Rommel had only a dozen of these guns, but the five at Halfaya Pass had been dug into stony clefts so that the barrels were at ground level. In the shimmering desert haze and with their flash-less charges, they were all but invisible.

On the second day of Battleaxe, Rommel threw in the tanks of the 5th Light Division and the newly arrived 15th Panzer Division, the second of the two divisions Hitler had promised Mussolini. While neither side could claim a clear-cut advantage, Rommel was gaining the upper hand. Most of his outposts, including Halfaya Pass (by now, and ever after, known to the British as Hellfire Pass), had held firm. The 5th Light was on the flank of the Desert Rats, and the German armor was better concentrated. Most important, Rommel had found British field commanders cautious and unimaginative, and he was ready to seize the initiative. He would “deal the enemy an unexpected blow in his most sensitive spot” by a flank attack at first light on June 17 before the British could launch any attack of their own.

Rommel stayed a step ahead of his enemy. By four in the afternoon of June 17, his panzer columns hooked in toward Halfaya Pass while the British rushed eastward to escape encirclement. The British lost twenty-seven cruiser tanks and sixty-four Matildas – almost half their armored force. The Afrika Korps won the battlefield as well as the battle and recovered and repaired its damaged tanks; in all, Rommel lost only a dozen tanks.

The British concluded from the failure of Battleaxe that their tanks were outgunned by those of the enemy, which was not true. This error grew out of misunderstanding what had killed so many of their cruisers and Matildas. They believed German tanks were responsible, when in most cases, the actual killers were antitank guns, particularly the eighty-eight. The failure to appreciate the full value of antitank guns, or how Rommel was using them, was to haunt the British in the months to come.

When the Battleaxe reports reached England, Winston Churchill was at Chartwell, his country home, where he was awaiting the outcome. There he received news of the defeat. “A most bitter blow,” he wrote, “I wandered about the valley disconsolately for some hours.” Beyond the fact that his beloved Tiger Cubs had been so roughly handled was the grimmer realization that, for the first time, the desert army had struck a full-strength blow, only to be repulsed.

The Middle East needed new blood, Churchill thought. He had lost confidence in General Wavell. On June 21, he cabled Wavell that “the victories which are associated with your name will be famous in the story of the British Army,” but that “the public interest will best be served” by a change in leadership. The new Middle East commander was to be General Sir Claude Auchinleck. Wavell would take Auchinleck’s place as head of British Commonwealth forces in India.

Wavell received the news from an aide early the next morning in his Cairo home as he was shaving. He showed no emotion as he listened to the orders, remarked quietly “the Prime Minister’s quite right – this job needs a new eye and a new hand,” and went on shaving. He took his usual morning ride and swim and set about getting affairs in order for his successor.

For nearly two years, in victory and defeat, Archibald Wavell had kept the Middle East in the Allied column. Certainly no other British soldier in World War II shouldered so many burdens. He built the foundations for victories that other men would win. When the change of command was made public, correspondent Alan Moorehead wrote: “There went out of Cairo and the Middle East that afternoon one of the great men of the war.”