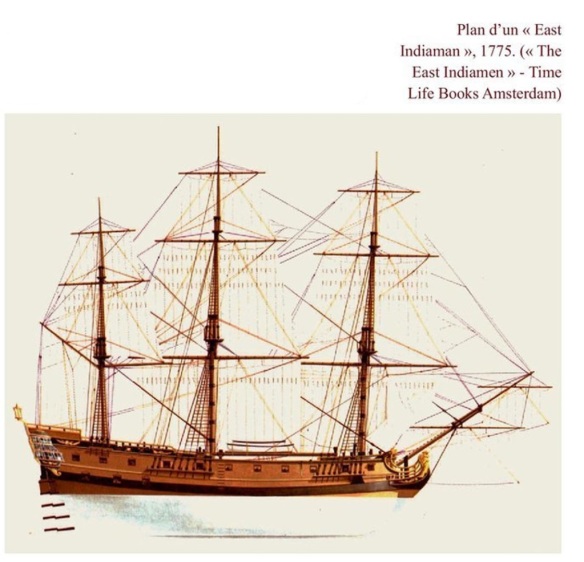

East Indiaman (Ship Type) Small, broad, roomy ships developed in the 1590s by the Dutch for trade with their colonies in the East Indies. Developed from the galleon and Dutch Fluyt, East Indiamen were rigged as frigates (square-rigged) and powerfully armed, to the point of equaling a man-of-war in fire power. They featured two galleries, a single forecastle deck, a quarterdeck, and a half-deck. Typical of the class was the Den Ary, which carried 54 guns and whose hull was clinker-laid up to the sides of both the half-deck and the quarterdeck.

Shortly after the Dutch, the British entered the East India trade, forming “The Governor and Company of Merchants of London trading to the East Indies,” also known as the Honourable East India Company [EIC]. Chartered in 1600, its ships, as were those of the Dutch, were well-armed and heavily manned. Similar, too, were the ships’ full underbodies, flat floors, sharp turns of the bilges, and quick rises. British East Indiamen were more apt to carry studding sails than were their Dutch counterparts and were frequently commanded by former Royal Navy officers. Quarters were often luxurious, and many vessels were adorned with gilding and ornamental carving.

British naval superiority in the Indian Ocean, arguably dates to Great Britain’s defeat of France during the Seven Years War (1756–63), but it was not cemented until their decisive victory over Napoleon. At the end of the eighteenth century, with the defeat of the Netherlands by France in 1795, Great Britain seized upon this enforced alliance between its main European and Indian Ocean rivals to take Cape Town, Ceylon (today Sri Lanka), and Java and Melaka from the Dutch, and the Mascarene Islands of Bourbon (now La Réunion) and Ile de France (now Mauritius) from the French. Twenty years later, by 1815, the British controlled the Cape, Ceylon, Melaka, and Mauritius, while Bourbon was returned to France by the Treaty of Paris. Just a few years later, the unauthorized occupation of Singapore by Stamford Raffles in 1819 and its formal possession by the British in 1823 almost immediately reduced the economic signifcance of both Melaka and Dutch Jakarta.

European maritime superiority did not go unchallenged in the early modern period. Along the coast of western India two rival indigenous navies clashed with each other and with the EIC to control coastal shipping. The most successful were the Sidis of Janjira Island, about forty miles south of Mumbai, who had ruled this fortifed island since 1618. Descendants of enslaved Africans known as habshis, a broad name denoting origins in northeast Africa, the Janjira Sidis traced their Indian roots to military service in the Deccan of southern India.

From the great fortress they constructed at Janjira, the Sidis became an important factor in coastal shipping north of Goa up to Bombay, whether serving the Mughals or their own interests. Sidi naval power was challenged by the powerful and ambitious Maratha ruler Shivaji Bhosale, whose army was seizing large chunks of western India from the Mughals. Shivaji commanded a series of small forts along the Konkan coast, as well as a fleet of perhaps several hundred ships. Although Shivaji is remembered as a militant Hindu ruler, in the typical Indian Ocean division of labor his ships were captained by Muslims. His several attempts to assert a naval presence on the coast proved to be disruptive to both the English and Portuguese, who were simultaneously contending with Maratha continental expansion. In the process of beating back the Maratha challenge, the Sidis momentarily shifted their alliance from the Mughals to the EIC, but they remained an independent if steadily less powerful coastal naval force deep into the nineteenth century.

The Yaarubi rulers of Oman drew most of their revenue from customs duties levied at their ports, but they also began to expand the date plantations along the Batinah coast of northeastern Oman. The demand for labor created by this agricultural plantation expansion, as well as the maintenance of a standing army by the Imam, were harbingers of increased slave trading to the Gulf from East Africa. Maritime raiding was apparently another source of revenue for Oman, such that Masqat gained a reputation as a pirate’s den. In 1705 an Omani attack on an EIC vessel caused one offcial to write that “Muskat . . . is become a Terror to all the trading people of India,” while a company pilot’s guide published in 1728 cautioned that “the danger of this port is as much from the Treachery of the Arabs as from the Storms and Rocks of the Coasts; for they are not only Pirates and Thieves, but Cheats in every thing wherein you can deal with them.”

By this time, however, internal dissension over election to the Imamate gave rise to civil strife in Oman. In 1749 a new dynasty, the Busaidi, came to power. Under the vigorous leadership of Ahmad b. Said, Oman’s place as a mercantile maritime power in the western Indian Ocean steadily grew. One immediate consequence of this political transition was that the Omani Mazrui governor of Mombasa rejected the new Busaidi claimant to authority. According to the anonymous nineteenth-century Swahili History of Mombasa, which only exists in Arabic renditions, “When the governor learnt that the Imam Ahmad bin Said had come to power, and that he was not of the family of the Imams, he declared himself ruler of Mombasa and refused to recognize the country as a possession of the Imam, and said: Formerly this Imam was my equal: he has now seized Oman, so I have seized Mombasa.” Mombasa’s independence would eventually be ended by Oman’s imperial expansion into East Africa in the long nineteenth century. From the middle of the eighteenth century, however, it was Great Britain that came to dominate the maritime space of the Indian Ocean as it built an empire based around India that eventually extended from South Africa, through the Gulf, across the Bay of Bengal and Malaya all the way to Hong Kong.