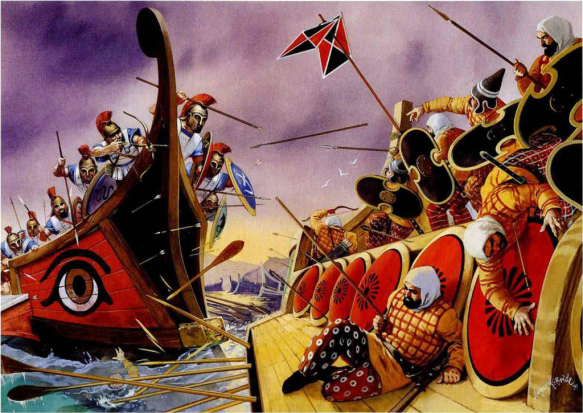

“Artemisia, Queen of Halicarnasuss, sinks a rival Calyndian ship within the Persian fleet at the Battle of Salamis, off the coast of Greece, 480 BC”

Battle of Salamis

No one who reads Herodotus’ narrative can underestimate the importance of the naval factor in the two Persian invasions. The Persians were an inland power and possessed no fleet of their own. It says all the more for the organizing ability of the Great Kings – Xerxes in particular – that they were able to muster such vast armadas. It also suggests that their knowledge of Greek seamanship and fighting power was such that they by no means despised the enemy with whom they had to deal.

The largest contingent of the Persian fleet consisted of Phoenician vessels, manned by Phoenician crews. Rather surprisingly, the Persians relied also upon ships and crews from the Greek Ionian cities which they had subjugated. Inevitably, they must have felt some doubts about the loyalty of the Greek contingents of their own fleet. On several occasions during the campaigns, the Ionian effort seems to have been half-hearted, and at the battle of Mycale the Ionian Greeks at last deserted their Persian overlords to aid their compatriots.

Artemisia, the Greek princess who ruled Halicarnassus (subject to Persian goodwill), was present herself on shipboard at the battle of Salamis, fighting on the Persian side. However, she seems to have joined either fleet as circumstances dictated at any particular moment, for when pursued by an Athenian vessel she deliberately rammed and sank another galley of her own contingent. The Athenians, thinking that she had changed sides, abandoned the pursuit and Artemisia made good her escape without further impediment.

The truth is possibly that Xerxes found it less risky to take the Ionian fleet with him than to leave it in his rear. On every ship there was a force of soldiers, either Persians, Medes or others whose loyalty was to be trusted. Persian commanders often took the place of local captains and Xerxes probably kept the leaders of the subject communities under his personal surveillance. Their position closely resembled that of hostages to the Persians.

Apart from the Phoenician and Greek naval contingents, there was in Xerxes’ fleet an Egyptian squadron which was to distinguish itself in the course of the fighting. We hear also of ships from Cyprus and Cilicia. Cyprus contained both Greek and Phoenician cities and the people of Cilicia were largely of Greek extraction. Whether the Cilicians felt any bond of sympathy with the Greeks of the mainland is another question, but only the links of empire united them with the Persians. The proportion of the total naval strength to that of the land army is recorded: the land forces, when counted by Xerxes at Doriscus in Thrace, were, according to Herodotus, 1,700,000 strong: the strength of the fleet is given with some precision as 1,207 vessels, not including transports.

The Structure of Ancient Ships

At this point something must be said of the construction of ancient ships in general and of ancient warships in particular. Mercantile and transport vessels were comparatively broad-beamed and correspondingly capacious. They had to depend on sails rather than oars if room was to be left for the cargo. The Greeks sometimes referred to them as “round ships”. By contrast, it may be remembered that the Latin for a warship was navis longa – a long ship. Throughout the ancient period which we are considering, warships were comparatively long and streamlined. They were built for speed and relied upon oars rather than sails. The Persians, in their two invasions, naturally needed both transports and warships.

The characteristic warship which developed about the time of the Persian Wars, and which was used in the battles with which we are concerned, was the trireme. This word is formed from the Latin; the Greek is trieres. The meaning is literally three-oared or triply furnished, but the reference is apparently to three banks of oars, which were ranged one above the other. At an earlier date, biremes, vessels of two oar-banks, were built. More common was the penteconter, a 50-oared galley with oars in a single bank. There were also triaconters, of 30 oars. Homeric ships had as few as 20.

Ancient ships, whether warships or transports, normally made use of single, square-rigged sails, and efficient performance required a following wind. Transports sometimes mounted two or, more rarely, three masts with a single yard and sail on each. Warships lowered their mast and sail before going into action. Steering was by means of two large paddles, one on either quarter. Battle tactics depended to a great extent on ramming the enemy, but boarding operations by heavily armed troops were also carried out and in this way prizes could be taken. Missiles were also used, although this method of fighting recommended itself more to the Persians than to the Greeks.

Persian Naval Strategy

It is interesting that Xerxes reverted to his father’s original plan and decided to invade Greece from the north. He must have considered that his channel through the Athos peninsula eliminated the main hazard of this route. Clearly, he could deploy a much larger army in Greece if his land forces could make their own way along the coast. At the same time, the fleet keeping pace on the army’s flank contained transports which considerably eased his supply problem. The land forces carried a good deal of their own baggage and equipment with the help of camels and other beasts of burden. These did not include horses. It was not customary in the ancient world to use horses for such purposes and it is noteworthy that Xerxes transported his horses by sea on special ships. Horseshoes were unknown in the ancient centres of civilization, and it is possible that the Persian cavalry might have reached Greece with lame mounts if their horses had been obliged to make the whole journey by land.

Warships were, of course, necessary to protect both the transports and the land forces. Without naval defence, the Persian army would have been exposed to the danger of Greek amphibious attacks on its flank and its rear. Moreover, it was Xerxes’ hope that he would crush any Greek naval units immediately, wherever he met them.

He met them first at Artemisium, on the northern promontory of Euboea. Several actions were fought there, with varying outcome. The Greek position was well chosen. In the narrow channel between the Euboean coast and the mainland, the Greeks could not be enveloped by superior numbers. At the same time, they guarded the flank of Leonidas’ forces at Thermopylae. If the Persians sailed round Euboea to attack them in the rear, then the Persian land forces would be separated from their seaborne support. What took the Greeks by surprise was the enormous size of Xerxes’ force, which despite all reports far exceeded their most pessimistic estimates. It was possible for Xerxes to send one section of his fleet round the south of Euboea while he engaged the Greeks at Artemisium with the remainder. Such a manoeuvre entailed no loss of numerical superiority on either front. But summer storms gathered over Thessaly and aided the Greeks. The very size of Xerxes’ fleet meant that there were not sufficient safe harbours to accommodate all the ships; a considerable part of it had to lie well out to sea in rough weather. In this way many ships were wrecked. When a squadron was dispatched to round Euboea and sail up the Ruripus strait, which divides the long island from the mainland, this contingent also fell victim to storms and treacherous currents. The task assigned to it was never carried out.

Quite apart from the figures given by Herodotus, events themselves testify to the huge size of the Persian armada. Despite the heavy losses suffered at Artemisium, Xerxes’ fleet still enjoyed the advantage of dauntingly superior numbers when, late in the same season, the battle of Salamis was fought. Even after Salamis, the number of surviving ships and crews was such that the Greek fleet at Mycale hesitated long before attacking them.