Didius Julianus secured his position as emperor by promising the Praetorian Guard 25,000 sestertii each. It was a generous offer, but proved too generous because Julianus had failed to consider whether he could pay it. He was gathered up by the praetorians who, displaying their standards, escorted the new emperor to the forum and the senate. The public display of power was deliberate and obvious and had the desired effect. Julianus indulged the conceit that he had come alone to address the senate while a large number of armed troops secured the building outside and a number came with him into the senate. It was a clear demonstration of where the real power lay, reminiscent of the accession of Otho in 69. Under the circumstances it was hardly surprising that the senate confirmed by decree that Julianus was emperor. He also ingratiated himself, or tried to, with the Guard by acceding to their personal nominees for the prefecture, in this case Flavius Genialis and Tullius Crispinus. His limited coinage focused to some extent on the army, with ‘Harmony of the soldiers’ being the principal offering. Conversely, Pertinax’s coinage had been far more general in its themes. Unfortunately for Julianus, not only did he lack the personal resources to fund the donative, but the imperial treasuries also remained barren after Commodus’ reckless reign. The praetorians were infuriated and started publicly humiliating Julianus, who was already gaining a reputation as greedy and indulgent.

Didius Julianus’ short-lived regime was already crumbling. In the east, Pescennius Niger, governor of Syria, had been declared emperor by his troops after news of the murder of Pertinax reached them. News of Niger’s ambitions reached Rome, where a frustrated populace started to protest in his favour. Part of the reason appears to have been a belief that Pertinax had been capable of arresting the rot that had set in under Commodus but had not been allowed to finish the job by the otiose and wasteful Julianus. Fighting broke out between the crowd and ‘soldiers’, which probably included the urban cohorts and the praetorians. Niger was by no means the only potential challenger. Lucius Septimius Severus, governor of Upper Pannonia, had allied himself to Pertinax, but on the latter’s death Severus had been declared emperor on 9 April 193 by his own troops. There was an irony in Severus’ status. He had been made one of twenty-five consuls appointed by Cleander, just before the latter was made praetorian prefect. In the west, Decimus Clodius Albinus, the governor of Britain, had also thrown his hat into the ring. The stage was set for another civil war. Severus was an arch manipulator. First he bought Albinus’ cooperation by offering him the post of heir apparent. Next, he set out first to secure Rome and then to destroy Niger. Severus was confident that in the meantime Julianus would be deposed; he could then turn against Albinus, destroy him and emerge, as Vespasian had in 69, as the supreme power in the Roman world.

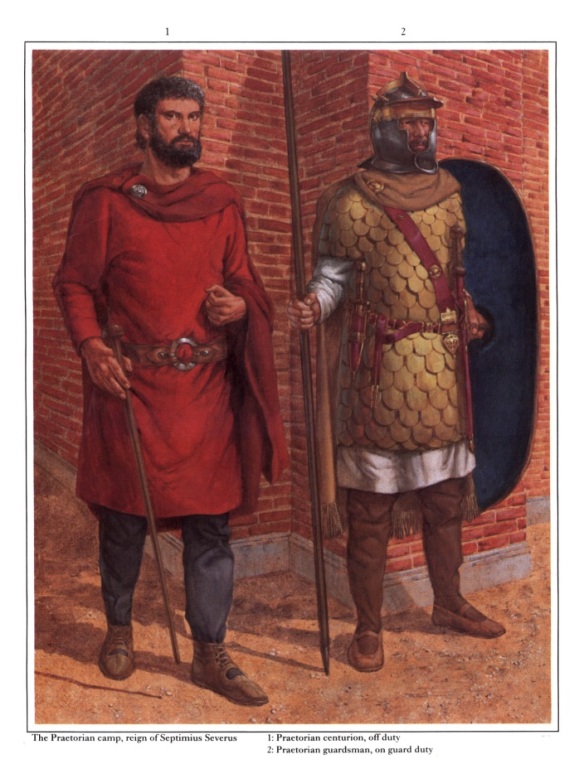

For the moment Julianus depended almost entirely on the fragile loyalty of the praetorians, men to whom he had promised a vast sum of money that he was unable to pay. His first move was inevitable, but futile. He ordered the senate to declare Severus a public enemy. His second was to have a defensible stronghold constructed and prepare the whole city for war, which included fortifying his own palace so that he could hold it to the end. Rome filled up with soldiers and equipment, but the preparations turned into a farce. Dio mocked what the praetorians and other available forces had become. Years of easy living, cultivated in the indulgent days of Commodus’ reign, had left the soldiers without much idea of what they were supposed to do. The fleet troops from Misenum had forgotten how to drill. According to Herodian, the praetorians had to be told to arm themselves, get back into training and dig trenches; this implies that they were accustomed to being unarmed and were completely out of condition. This depiction of the Praetorian Guard, however, suited the purpose of Dio and Herodian. A stereotyped derelict and incompetent Guard amplified the impression of the decadence of Commodus’ reign and the incompetence of Didius Julianus, as well as creating a gratifying image of grossly overpaid and indolent public servants getting their comeuppance. Nevertheless, the indolence probably had a basis in truth and might also have been linked to a conservative attitude to equipment. By the end of the second century AD praetorian infantrymen were still habitually equipping themselves with the pilum, while legionaries had spurned this in favour of various new forms of javelin.

The praetorians became agitated. Not only were they completely overwhelmed by all the work they had had to do, but they were also extremely concerned at the prospect of confronting the Syrian army under Severus that was approaching through northern Italy. Julianus toyed with the idea of offering Severus a share in the Empire in an effort to save his own skin. The praetorian prefect Tullius Crispinus was sent north to take a suitable message to this effect to Severus. Severus suspected that Crispinus had really been sent on a mission to murder him, so he had Crispinus killed. In his place Julianus appointed a third prefect, Flavius Juvenalis, whose loyalty Severus secured by writing to him confirming that he would hold the post when he, Severus, took power. There is some confusion here. The Historia Augusta calls the third prefect Veturius Macrinus, so conceivably two new prefects had been appointed, both of whom seem to have transferred to the Severan regime. Severus sent letters ahead, perhaps via Juvenalis, promising the praetorians that they would be unharmed if they handed over Pertinax’s killers. They obliged, and this meant that Julianus was finished. Severus also sent an advance force to infiltrate the city, disguised as citizens. The senate, realizing that the praetorians had abandoned Julianus, voted that Julianus be executed. This happened in short order on 2 June 193. Next they declared Severus to be the new emperor. Didius Julianus had reigned for a little over two months. In the space of five months in 193 the Praetorian Guard had played their first truly significant role in imperial events for well over a century. They had toppled an emperor and installed another, only to abandon him with unseemly haste, contributing significantly now to the inception of a new dynasty whose members would rule the Roman world until 235. Not since 69 had the praetorians made so much difference, though, ironically, it seems that in 193 as troops they were no more than a shadow of their former selves. They were to pay a heavy price for their interference in imperial politics.

The transition of power was not as smooth as the praetorians hoped. Their tribunes, now working for Severus, ordered them to leave their barracks unarmed, dressed only in the subarmilis (under-armour garment) and head for Severus’ camp. Severus stood up to address them but it was a trap. The praetorians were promptly surrounded by his armed troops, who had orders not to attack the praetorians but to contain them. Severus ordered that those who had killed Pertinax be executed. This act was to have consequences forty-five years later when another generation of praetorians believed they were about to be cashiered too. Severus harangued the praetorians because they had not supported Julianus or protected him, despite his shortcomings, completely ignoring their own oath of loyalty. In Severus’ view this ignoble conduct was tantamount to disqualifying themselves from entitlement to be praetorians; oddly, the so-called ‘auction of the Empire’ seems to have gone without mention.

Severus had a very good reason for adopting this strategy. It avoided creating any impression that he was buying the Empire as Didius Julianus had, even though previous emperors, including very respectable ones like Marcus Aurelius, had paid a donative. Firing the praetorians en masse also saved him a great deal of money, in the form of either a donative or a retirement gratuity. Given the cost of Severus’ own war, and the appalling state of the imperial treasuries, this must have been a pressing consideration. The normal practice would have been for the emperor to pay a donative out of his own pocket. Severus was prepared to spare the praetorians’ lives but only on the condition that they were stripped of rank and equipment and cashiered on the spot. This meant literally being stripped. They were forcibly divested by Severus’ legionaries of their uniforms, belts and any military insignia, and also made to part with their ceremonial daggers ‘inlaid with gold and silver’. Just in case the humiliated praetorians took it into their heads that they might rush back to the Castra Praetoria and arm themselves, Severus had sent a squad ahead to secure the camp. The praetorians had to disperse into Rome, the mounted troops having also to abandon their horses, though one killed both his horse and then himself in despair at the ignominy.

Only then did Severus enter Rome himself. Rome was filled with troops, just as it had been in 68–9. This agitated the crowd, which had acclaimed him as he arrived. Severus made promises that he did not keep, such as insisting he would not murder senators. Having disposed of the Praetorian Guard in its existing form, Severus obviously had to rebuild it. He appears to have done so with Juvenalis and Macrinus still at the helm as prefects in reward for their loyalty over the transition. Severus’ new Praetorian Guard represented the first major change in the institution since its formation under Augustus and amounted to a new creation. Valerius Martinus, a Pannonian, lived only until he was twenty-five but by then he had already served for three years in the X praetorian cohort, following service in the XIIII legion Gemina. XIIII Gemina had declared very early on for Severus so Martinus probably benefited from being transferred to the new Guard in 193 or soon afterwards. Lucius Domitius Valerianus from Jerusalem joined the new praetorians soon after 193. He had served originally in the VI legion Ferrata before being transferred to the X praetorian cohort where he stayed until his honourable discharge on 7 January 208. Valerianus cannot have been in the Guard before Severus reformed it in 193, so this means his eighteen years of military service, specified on the altar he dedicated, must have begun in the legions in 190 under Commodus. Therefore it is probable most of his time, between 193 and 208, was in the Guard under Severus. One of the most significant appointments to the Guard at this time was a Thracian soldier of epic height who began his Roman military career in the auxiliary cavalry. In 235 this man would seize power as Maximinus, following the murder of Severus Alexander, the last of the Severan dynasty.

Dio’s reference to there being ten thousand men in ten cohorts in AD 5 is sometimes assumed to be a reference really to the organization of the Guard in his own time, the early third century. It is possible that ten praetorian cohorts had been in existence from Flavian times on. It is beyond doubt, however, unusually for this topic, that from Severus onwards, the Praetorian Guard consisted nominally of ten thousand men in ten milliary cohorts as Dio had described. Diplomas of the third century certainly confirm that thereafter there were ten cohorts. A crucial change made by Severus was to abolish the rule that the praetorians were only recruited from Italy, Spain, Macedonia and Noricum. Instead any legionary was eligible for consideration if he had proved himself in war. This had the effect of making appointment to the Guard a realistic aspiration for any legionary. The idea was that by recruiting from experienced legionaries, the Severan praetorian would now have a far better idea of how to behave as a soldier. This was not always the case. By the time Selvinius Justinus died at the age of thirty-two in the early third century, he had already served seventeen years in the VII praetorian cohort. Unfortunately, there was an unintended consequence, or so Dio claimed. Italians who might have found a job with the Guard now found themselves without anywhere to go and resorted to street fighting, hooliganism and generally abusive behaviour as a result. Rome also now found itself home to provincial soldiers whose customs were regarded as lowering the tone. The reports seem likely to be exaggerated. A Guard of around ten thousand men would hardly have absorbed all of Italy’s disaffected young men. Nor would ten thousand provincial praetorians have changed the character of Rome, especially as many of the new praetorians clearly spent much of their time on campaign. An interesting peripheral aspect to this story is that the paenula cloak, apparently part of the Praetorian Guard’s everyday dress, seems to have dropped out of use by the military by this date; it had, perhaps, become discredited by association with the cashiered praetorians.

Severus had more pressing concerns for the immediate future. He had to dispose first of Niger and then turn on Albinus. Niger was defeated at Issus in Cilicia in 194. He fled to Parthia but was caught by Severus’ agents and killed. Severus was distracted by various rebellions in the east before he was able in 196 to turn his attention to Clodius Albinus in the west, still nursing ambitions of becoming emperor after Severus even though Severus had withdrawn the title of Caesar from him. The climax came at the Battle of Lugdunum (Lyon) in Gaul in a vast engagement in which the Praetorian Guard played an important part. The figure claimed by Dio for the battle of 150,000 men in each army is simply enormous and equivalent to around thirty legions each, an implausibly vast number. It is better interpreted as the figure for both armies together, but there cannot be any doubt that the engagement was of major significance.

The battle began badly for Severus because Albinus had placed his right wing behind concealed trenches. Albinus ordered the wing to withdraw, luring the Severan forces after them. Severus fell into the trap. His forces raced forwards, with the front lines crashing into the trenches. The rest stopped in their tracks, leading to a retreat with a knock-on effect on the soldiers at the back, some of whom collapsed into a ravine. Meanwhile the Albinians fired missiles and arrows at those still standing. Severus, horrified by the impending catastrophe, ordered his praetorians forward to help. The praetorians came within danger of being wiped out too; when Severus lost his horse it began to look as though the game was up. Severus only won because he personally rallied those close to him, and because cavalry under the command of Julius Laetus, one of the legionary legates from the east who had supported Severus in 193, arrived in time to save the day. Laetus had been watching to see how the battle shifted before showing his hand, deciding that the Severan rally was enough to make him fight for Severus. It is a shame we do not know more about how many praetorians were present, and exactly how they were deployed but, given the claimed numbers involved in the battle, it seems very likely that all, or at least most, of the praetorians were amongst them. If so, the reformed Praetorian Guard must have been very nearly destroyed within a very few years of being organized because it is certain the body count on the battlefield was enormous.

The Battle of Lugdunum marks a point in the history of the Praetorian Guard when it seems to have become normal for all or most of the Guard to be deployed away from Rome as part of the main army. Conversely, it also represented a return to the way praetorians had been deployed during the period 44–31 BC. The only praetorians likely to be left in Rome during a time when the Guard was needed for war were men approaching retirement. The II legion Parthica, formed by Severus, was based at Albanum, just 12 miles (19 km) from Rome from around 197 onwards. The legion would clearly have helped compensate for the absence of the Guard so long as some of the legion was at home. It also bolstered the number of soldiers immediately available to the emperor as a field army, without having to rely entirely on the Guard or troops pulled from frontier garrisons. Alternatively it could fulfil some of the Guard’s duties if the emperor took praetorians on campaign with him. A praetorian in Severus’ Guard could expect to see a great deal of action. Publius Aelius Maximinus was a soldier in the V praetorian cohort under Severus. On his tombstone he was said to have participated ‘in all the campaigns’, which suggests that going to war had become routine for praetorians, though it simply could have been a stock, rather than a literal, claim. Since the tombstone was found in Rome, Aelius Maximinus had presumably lived to tell the tale, expiring at some point after his return, though he was only thirty-one years and eight months old when he died.

The soldiers who took part in Severus’ wars and who earned the right to transfer to the new Praetorian Guard found that a further Severan change in terms and conditions was an increase in length of service to eighteen years. This could include the time spent as a legionary. Lucius Domitius Valerianus was discharged in 208 after serving eighteen years. He had been recruited into the VI legion Ferrata in around 190 under Commodus, from which he transferred to the X praetorian cohort at an unspecified later date, serving in the century of Flavius Caralitanus. The date of discharge is provided by the reference to the joint consulship of Severus’ sons, Caracalla and Geta, which they held that year. The VI legion Ferrata had been based in Syria since at least AD 150 and had formed part of the eastern army supporting Severus, being awarded with the title Fidelis Constans (‘always faithful’) for not siding with Niger. The funerary memorial of another praetorian of this era, Lucius Septimius Valerinus of the VIIII praetorian cohort and formerly of the I legion Adiutrix, shows him bareheaded in the traditional praetorian tunic with sword at his side and holding a spear.

The Praetorian Guard as an institution survived to fight another day for Severus. It remained an important symbol of imperial power and Rome’s military strength. A praetorian standard was featured on the so-called Arch of the Moneylenders, dedicated in Rome in 204. With Albinus destroyed and his supporters executed, Severus returned to Rome before turning his attention to Parthia in 198. A cash handout to the Roman people was accompanied by a large payment to ‘the soldiers’, as well as a pay rise and other privileges, such as being able to cohabit with wives. These must have included praetorians, but quite to what extent is unknown as the reference is to the army in general. Herodian was acutely critical of how the new arrangements could undermine military discipline.