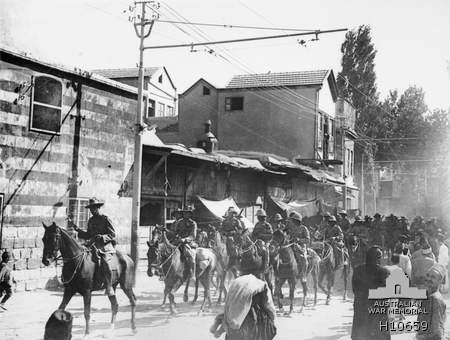

Lieutenant General Sir Harry Chauvel commanding Desert Mounted Corps leads his corps through Damascus on 2 October 1918.

Prince Feisal leaving Chauvel’s Desert Mounted Corps Headquarters in Damascus.

With the Ottoman military position in Palestine, Syria, and Mesopotamia collapsing at late autumn of 1918, the Arab Secret Society seized control in Damascus. On October 1, in a sequence preplanned by the commander of the EEF, the first troops of the Arab Revolt rode into the city followed on October 2 by Allenby’s forces. During the month of October, Allied forces under Allenby seized Beirut (present-day Lebanon) on October 8; Tripoli on October 18, and the great trading city of northern Syria, Aleppo, on October 25. On October 30, 1918, with all lands outside of Anatolia (present-day Turkey) essentially lost in terms of the Middle East, Istanbul sued for peace and asked for an armistice. The Battle of Megiddo was certainly one of the best planned and executed British battles of the First World War and most certainly that which followed in the aftermath was historic in scale as Britain and France took positions of prominence across the Middle East in the wake of the collapse of the Ottoman Empire.

CRITICAL THINKING AND ADAPTABILITY IN MODERN WAR

Reforming the Ottoman military had been a pressing issue for successive Sultans for at least two centuries in the early modern era and in the lead-up to the First World War. An entrenched bureaucracy, backed by the powerful Janissaries and elite merchants who were quite content with the Ottoman status quo, successfully hindered the necessary reforms. Yet, the reforms needed for successful military operations in the modern, industrialized world went beyond the need to reorganize army units and train their leaders.

As was the case in many of the battles that took place during World War I, in any theater, battle communications with the front were generally broken in short order. Since nearly no battle plan survives, first contact with the enemy fully intact, those in the front lines are unable to receive new orders or benefit from new intelligence other than what they are generating on their own. Accordingly, while brilliant generals and field marshals construct plans that come from a career of experience and study, the original plan most often needs to be adjusted in the face of enemy action.

If, as was widely the case during the war, those at the front cannot communicate with the brilliance in the rear, they are then left to fend for themselves. It is the ability of these officers and men to adapt, adjust, and overcome. Conversely, it is their inability to do so that often factored significantly into the outcome of battle. It was, therefore, the intent of the Ottoman leadership to allow Germany to help develop Auftragstaktik at the general officer level and where appropriate, within its mid-level officer ranks. In the drill regulations of the infantry 1888, German commanders were told to tell subordinates what to do without insisting on how they did it. Due to the increased lethality of modern weapons, it was expected that greater force dispersion would be required. Given this, captains and lieutenants would often find themselves required to direct their units without orders from central command. As such, the nature of the decentralization of the modern battlefield created the necessity of developing initiative, critical thinking, and independent judgment at all levels.

Yet, the ability to think independently, critically, and accurately in the midst of uncertainty, chaos, violence, and danger requires a culture that fosters, over a lifetime, a culture of innovative and courageous behavior. Accordingly, in order to be successful militarily in modern battle-space, traditional and authoritarian societies are faced with a dilemma: continue insisting on a compliant and submissive population producing military leaders incapable of fast and independent thinking or launch societal-wide reforms in the nature of education, socialization, and training, which will empower their commanders and decision makers to adjust quickly and effectively in the heat of modern-era battle.

In essence, the centralized power of the typical autocratic political regime within the Middle East will not simply have to reform in order to create modern democratic societies, rather, and perhaps more importantly, it will have to embrace change in order to defend itself in the modern battle-space. The centralized command structure with initiative and independent thinking suppressed in many of the armies within the modern Middle East will have to be overcome in order to prosecute effective military campaigns in the modern era. The need for military security will require changes in traditional society, which will, in turn, create the conditions leading ultimately toward greater political participation and greater democratization across the region.

This is not to suggest that Ottoman officers, had they been better at operating independently, would have prevailed over Allenby’s forces during the campaign in Palestine during the First World War. It does suggest that given the realities of modern warfare, successful military officers will be forced to think in new and different ways and will benefit from being schooled in the science and art of critical and innovative thinking. The plight of the Mamluks in the face of a rising and technically proficient Ottoman army and their subsequent refusal to adapt to new weaponry and doctrine serve to illustrate the gravity of the situation for Middle Eastern cultures as the twenty-first century unfolds. Allenby’s Middle East operations were instrumental in driving Ottoman and German forces from the Levant, the liberation of Arab lands from Turkish rule, as well as laying the foundation for the arrival of the Jewish people and the ultimate establishment of the state of Israel. As such, Allenby, the EEF, and the Cairo-based Arab Bureau’s contributions to the creation of the modern Middle East are substantial.

MODERN WARFARE AND STRATEGIC ENDURANCE

In order to conduct modern, industrialized warfare at the great power level, the ability to generate and sustain strategic endurance had become, by the First World War, a prerequisite for success. Accordingly, the great powers, particularly Britain, France, Germany, Russia and the Ottoman Empire, maneuvered for control of those elements that contributed to strategic endurance: people, resources, markets, and trade routes. These crucial elements or components of aggregated power and the direction of that power for the obtainment of political objectives were certainly not new or unique to the modern world having animated world politics for centuries. What was new were the nature of energy, electricity, machining, and mass production, coupled with an exponential rise in the levels of lethality, range, and accuracy of rapid fire small arms and large bore artillery.

Long lasting wars between great power coalitions in the modern age have been won by the side with the largest economic staying power and productive resources. In every economic category, the Anglo-American-French coalition was between two and three times as strong as Germany and Austria-Hungary combined—a fact confirmed by further statistics of the war expenditures of each side between 1914 and 1919: 60.4 billion dollars spent by the German-Austrian alliance as opposed to 114 billion spent by the British Empire, France and the United States together (and 145 billion if Italy and Russia’s expenditures are included).

Given the militarization of the various industrialized economies, as well as the mobilization of the entire populations for prolonged periods, the First World War came to be referred to as a “total war.”

The militarization of societies, economies, and politics was the consequence. In the end, the war proved a contest of productive capacities; and the Allied victory was due to their material superiority, which by 1918 was insuperable.

In order to form sufficient levels of aggregated power that would lead to a war-winning level of strategic endurance, Britain needed to borrow heavily (particularly from the United States and the banking syndicates in Europe) and was forced to make promises that were eventually difficult to honor. After the defeat of the Ottoman Empire and its Central Powers’ allies, the promises that Britain had made in order to cobble together the winning coalition were, by 1919, beginning to color its postwar Middle East policy. Sharif Ali Hussein and his sons, Faisal and Abdullah, called for the promises made during the Hussein-McMahon correspondences to be honored by establishing an independent Arab state and to be placed under Hussein’s control.