The Mongol devastation of Hungary alerted western Europe to what might be in store for it: but suddenly Batu and his hordes were gone, the danger was over and Europe could breathe again. From that day to this the question of why they turned back has exercised historians. The most commonly accepted ‘explanation’ is that after Ogodei’s death every Mongol was bound in duty to return to Mongolia to elect his successor. Accepting the (likely) cause of the khan’s death as poisoning by his aunt, as against the convenient notion that it was alcoholism, a leading Russian historian has commented: ‘This woman, whoever she was, must be considered the saviour of Western Europe.’

But this idea is not convincing, for a number of reasons. In the first place, the quriltai that elected Guyuk as khaghan did not take place until 1246, four and a half years after Ogodei’s death. Secondly, Batu did not return to Mongolia (lingering, as we have seen, in the Volga region), for he was very well informed about all the intrigues that flickered through Karakorum after Ogodei’s death and thought (rightly) that his life would be in danger.

Thirdly, senior commanders and Mongol notables were not in any case automatically recalled to Mongolia after Ogodei’s death. The most salient example is that of Baiju, Mongol commander in Iraq and western Iran, whom Ogodei had appointed as Chormaqan’s successor. On 26 June 1243 Baiju won a shattering victory over the Seljuk Turks under Kaykhusraw II at Kose Dag against the odds. (Allegedly he dismissed the numerical superiority of the Seljuks with a typical Mongol comment: ‘The more they are, the more glorious it is to win and the more plunder we will secure.’) As a result of this triumph, which made the years 1241–43 rival 1220–22 for non-stop Mongol victories, the empire of Trebizond in Anatolia submitted to Baiju and his armies were able to advance into Syria. But there was no question of his having to return to Mongolia for a quriltai.

Another possible explanation is that the Mongols abandoned the idea of an invasion of western Europe because the terrain, largely forested and with no great plains, would not have provided the forage and pasture needed for their horses and other animals. It is alleged that even in Hungary the Mongols were operating to the limit of their capacity, for the puszta, the Great Hungarian Plain, was the only area of grassland west of the Black Sea capable of supporting horses on any scale; here they were limited to 40,000 square miles, as against the 300,000 square miles in the great steppes of their homeland. To feed 100,000 horses one would need 4,200 tonnes of grain in winter or summer, and where would this come from unless, implausibly, it was transported 8,000 miles from Mongolia? Additionally, warhorses needed a lot of care from grooms and wranglers, increasing the numbers the Mongols would have to deploy, and were susceptible to precisely the diseases and parasites that the cold and damp of northern Europe would engender.

Against this theory one can cite factors which might be considered ‘circumstantial evidence’. The Mongols were capable of adapting their military methods, as they demonstrated in the long war with Song China and particularly under Qubilai when they attempted conquests in Burma, Vietnam, Indonesia and Japan – though, with the exception of the conquest of Song China, it is notable that none of these campaigns was successful. Napoleon operated with huge numbers of horses in his conquests and as late as the Second World War the Germans were able to utilise millions of horses even with the depleted grazing grounds in industrial Europe. One can, however, argue that such comparisons are anachronistic: by the time of Napoleon much more of Europe had been converted to pasture, and in the case of the Second World War one has to factor in railways, superior veterinary corps and mobile horse transports, none of which was available to the Mongols. Tellingly, though, the Huns under Attila, also entirely dependent on horses for their military superiority, fought campaigns in Italy and France, where it was not problems of pasture that halted them. A judicious conclusion would be that horses and pasturage certainly played some part in the Mongol decision to withdraw.

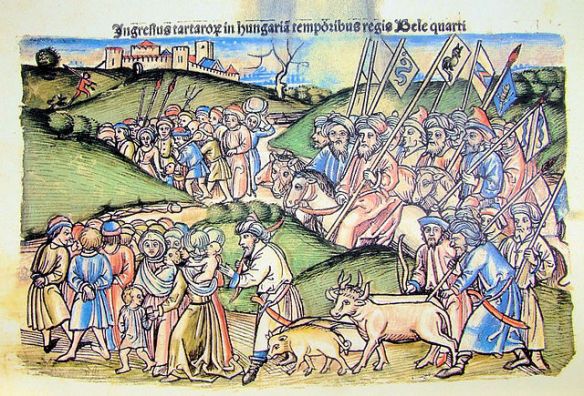

Another popular theory is that the entire question is misplaced, since the Mongols never intended to conquer western Europe. According to this version the Mongols invaded Hungary purely to punish Bela for having harboured the Cumans and to ensure that there could be no threat to Batu’s ulus in Rus – the Golden Horde. This idea has the merit of simplicity – for the Mongol withdrawal would then need no explanation – but is in conflict with a mass of inconvenient evidence, not least that the Mongols were hopelessly divided. In short, while this was almost certainly Batu’s aim, it was not Subedei’s, as he stated that his dream was to behold the Atlantic. There is no documentary evidence as to what exactly Ogodei’s instructions to his two commanders were, but it is likely that they were issued on a contingency basis – that if the conquest of the Rus states and eastern Europe went well, he would provide the necessary resources for the conquest of western Europe.

What is certain is that Batu’s decision to return to the Volga caused a major rift with Subedei. He cut all his links with Batu, rode back to Mongolia with his retainers and openly supported Guyuk and the houses of Ogodei and Tolui against Batu and the house of Jochi. He avoided all involvement in the murderous intrigues of 1242–46 but was present in 1246 at the quriltai that elected Guyuk. He then retired to the homeland of his Uriangqai tribe east of Lake Baikal, where he died in 1248 aged 72. His son Uriankhadai went on to great things under Mongke in the war against the Song.

It is fairly clear from all the evidence that Subedei, Ogodei and Guyuk all wanted to conquer western Europe. Carpini in 1245 reported that Guyuk had a threefold project: election as khaghan, defeat of Batu in the civil war that had by then broken out between them, and then a fresh invasion of Poland and Hungary as a launch-pad for the conquest of Germany and Italy. Guyuk claimed he wanted to attack Germany first, and proved that he had very good intelligence about the emperor Frederick’s military capability, but Carpini told his colleague Salimbene di Adam he was convinced that Guyuk’s real objective was Italy, both because of its wealth and because that was where ‘Stupor Mundi’ (not to mention the Pope) had his power base. Despite Carpini’s boasting about German military might, which implied that the choice of Italy was the softer option, the likelihood is that the Mongols, knowing of the emperor’s predilection for Italy, had simply decided to go for the jugular.

Carpini noted that Guyuk was supremely realistic and was planning for a campaign that was expected to last eighteen years before victory was assured. As to the chances of success, the consensus of historians then and since was that the Mongols would have reached the Atlantic, but only provided their empire was united in a concerted, monolithic endeavour. Nor would Byzantium have been spared, as a Byzantine expert has pointed out: ‘The successors of Genghis Khan . . . could doubtless have swept the Byzantine as well as the Latin and Bulgarian empires out of existence had the mood taken them.’ This was all the more so since, whereas the Mongols knew every last nuance of European politics, the West was still mired in ignorance about them, variously identifying them as the Ishmaelites or the Antichrist, the forces of Satan, the chaos world, the allies of heterodoxy, anarchy and disorder, fomenters of Islam, Cathars, Lombardy separatists or even the shock troops of an international Jewish conspiracy.

The West, in short, was long on emotion but short on reason and intelligence. Carpini claimed to have discovered the secret of how the West could defeat the Mongols in battle, but this was no more than propaganda to keep Western spirits up. While he whistled in the dark, more sober observers were stupefied by the Mongol withdrawal and suspected it might be like the Greeks’ abandonment of Troy when they left behind the wooden horse. Matthew Paris thought the ‘Tartars’ would come again and that nothing could stop them reaching the Atlantic. The Council of Lyons in 1245 heard an estimate from one bishop that the war with the Mongols might well last thirty-nine years – it is not clear where this exactitude came from.

The sober truth was that by 1242 the Mongol empire was hopelessly divided by faction fighting, that civil war loomed and that anything so momentous as an invasion of Western Europe was not remotely conceivable. Batu, in short, withdrew from Europe because of manpower shortages and the looming conflict with Guyuk, and retreated to the upper Volga to prepare for the trial of strength which he knew would come.

His main problem was an acute lack of men. Once it was known that Ogodei was dead, the levies formerly loyal to Guyuk and Buri demanded to be allowed to return home, and there was nothing Batu could do to stop them unless he wanted a mini-civil war in his own empire; Mongke went with them, taking back to Karakorum his own anti-Batu version of the infamous banquet and the subsequent feud. It was then that Batu showed his calibre as a politician. He may have been mediocre as a battlefield commander but he excelled in diplomacy and intrigue. Even before Ogodei died, while Batu planned the future of what would become the Golden Horde, he decided to shore up his position by seeking allies among the Rus princes, and he proved a shrewd picker.

Deeply unpopular with Novgorod’s boyars, Alexander Nevsky had left the city for two years after his victory over the Swedes at the Neva but was then hurriedly recalled when the Teutonic Knights invaded Russia and took the city of Pskov to the west of Novgorod. Purging the pro-German clique in Novgorod, Nevsky engaged the knights and their allies in a minor battle on the ice of Lake Peipus on 5 April 1242. The numbers involved on both sides were not large; only about one hundred Teutonic knights took part, with the rest of their army being Swedish and Lithuanian volunteers. Nevsky won a complete victory, though the Suzdalian chronicle attributes the real merit in this success to Alexander’s brother Andrei. Only about twenty knights were killed (‘hardly indicative of a major encounter’ as a sceptical historian notes), and there was no mass destruction when the German army plunged through the ice after it gave way under their weight. Russian nationalists such as the Metropolitan Kirill in his Life of Nevsky elevated what was not much more than a skirmish to one of the great battles of the ages; Soviet propagandists reinforced this bogus view and this is the perception that has stuck. Nevsky, meanwhile, was acclaimed as one of the very greatest Russian heroes, and canonised by the Orthodox Church both for his staunch opposition to overtures from an ecumenical Vatican and for his stoical and self-denying submission to Mongol rule.

The historical Nevsky, as opposed to the legendary creature so beloved in Russian mythology, was a slippery and serpentine character. The most significant thing about the battle of Lake Peipus is that Batu’s envoys were present at Nevsky’s side as military advisers; certainly the threat from the Teutonic Knights was the most important factor leading him to throw in his lot with the Mongols. In fact Nevsky’s relations with the Mongols were a tale of ambivalence and duplicity, with the hero self-servingly and ruthlessly focusing on his ambitious political goals; it was this that dictated his unswerving loyalty to Batu and his successors.

Batu rewarded him by supporting him against his brother Andrei, who favoured religious rapprochement with Rome. The Mongols were very hard on Russians who tried to entangle the Vatican, thought to be the ‘nerve centre’ and real seat of power in the West. When Alexander’s father Grand Prince Yaroslav seemed likely to renounce Russian Orthodoxy and submit to the papacy, the Mongols had him poisoned, though authorities differ on whether the ‘contract’ on his life was ordered by Batu or Ogodei’s widow Toregene. After Batu’s death Nevsky enjoyed particularly good relations with the next khan of the Golden Horde, Sartaq (he was said to have entered into an anda relationship with him) who became a Christian. Even though Sartaq was probably poisoned by his uncle Berke, who succeeded him and converted to Islam, Nevsky continued on amicable terms with the new khan. As he had shown in the case of his father, and now his blood brother, Nevsky was not the kind of person to allow emotion and sentiment to get in the way of realpolitik.

Ogodei’s death really signalled the end of the Mongol empire that Genghis had striven so hard to found, though the formal structure continued in existence until the end of the 1250s. Guyuk was not elected as khaghan until 1246, a delay which had a fourfold explanation. It took that long for his mother, the Regent Toregene, to muster the necessary support; there was uncertainty about Batu’s intentions, with Subedei vainly trying to act the honest broker and reconcile him and Guyuk; there was a general moral crisis in Mongolia because of the widespread rumour that Ogodei had been poisoned; and the shamans all declared that an early election would be inauspicious.