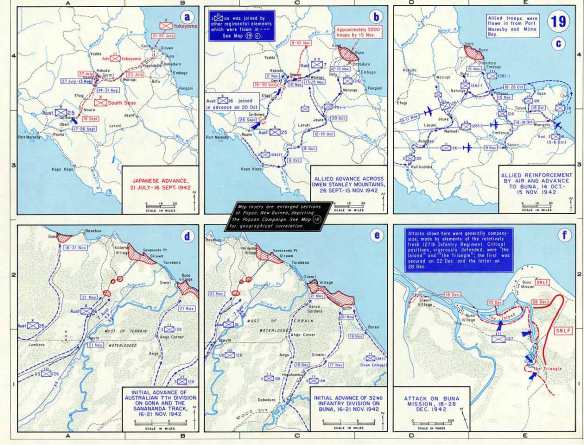

After landing 3,000 men unopposed, at Lae on March 8th, the Japanese had little to fear from the allies. It was MacArthur’s obsession with the liberation of the Philippines that was to make New Guinea the lure for thousands of American, Australian and Japanese troops to fight for it’s uninviting jungle. It was a pivotal point for any invasion of the Philippines, it also blocked any invasion of Australia by the Japanese and could sever the America/Australia lifeline if taken by the Japanese. After the Japanese invasion at Buna, MacArthur and the Australian General Blamey often fell out, as the Australian militia fell back before the Japanese onslaught MacArthur felt that the ‘Aussies’ were poor fighters, often retreating before inferior Japanese forces. He lingered under the impression that American troops would do much better. As the Japanese continued their advance over the Owen Stanley mountains towards Port Moresby, the allied situation became desperate, the landings at Guadalcanal had turned into a bloody slogging match of grinding attrition and at the same time the Japanese launched a two pronged attack on Port Moresby.

As General Horii’s troops launched their overland offensive, (on August 24-25th) the Navy landed 2,500 troops at Milne bay. From Milne however, the Japanese had to advance along a single muddy track and soon clashed with the Australians guarding it. During frequent downpours the Japanese launched several night attacks using light tanks, machine guns, grenades and bayonets. Despite their fanatical attacks, the Japanese could make no headway against the determined Aussies and after several days they evacuated their surviving troops. It was during these actions that Maj. General Kenney the new allied air commander made his debut. Despite not achieving much against the Japanese at Milne Bay (the 5th Air Force mistakenly bombed Australian troops) Kenney learned quickly and his innovations and adaptability proved to be very valuable in the harsh jungle airstrips the 5th was forced to operate from.

As the Japanese attack on Milne was being repulsed, more good news arrived. Horii’s attack force had shot it’s bolt during the overland offensive, tired, dispirited by the jungle fighting and with Horii himself drowned while crossing a river, the Japanese fell back under ferocious Aussie counterattacks. MacArthur now struck at Buna, using the 32nd Infantry Division. Everyone expected it be a walk over, basically just ‘mopping up’ stray Japanese troops, instead the men of the 128th Infantry, 32nd Div, walked into a jungle nightmare. Reinforced by fresh troops, the Japanese holding Buna, Sanananda and Gona could not be outflanked as the villages all backed up to the ocean and so the Americans had to advance through swamps and jungle to launch frontal attacks against the dug in Japanese. Japanese infantry would wait in their foxholes until the Americans passed by, then attack them from the rear while machine guns peppered the Americans from the front. Besieged by insects, soaked by frequent downpours and in a kind of combat that they had not been trained for, the 128th stopped dead in its tracks. MacArthur was especially embarrassed because, as reports of cowardice, malingering and inaction filtered back to him, the ‘unreliable’ Australian troops of the 7th Division pressed home their attacks regardless of harsh conditions, small parties of troops crawled through the slime to attack strong-points, destroying each bunker in turn, while living in vile conditions.

In the close quarter fighting the Japanese ravaged the Aussies who kept hammering away at the Japanese positions until they took Gona on the 9th of December. The 7th Division was finished as a fighting force however, battle casualties and malaria had exacted a terrible toll. The Americans on the other hand were still stuck in the swampy morass around Buna and Sananada and on the 29th of November, an irate MacArthur told General Eichelburger to “take Buna or don’t come back alive!” After relieving the hapless General Harding and reinforced by tanks and additional artillery, the 128th finally took Buna on January 2nd, 1943, Sanananda fell 20 days later. As many as 13,000 Japanese troops lost their lives during the fighting and allied casualties were about 8,500 battle casualties (5,698 of them Australians) with another 25,000 cases of malaria.

With his three months of unimaginative attrition warfare, MacArthur had won the airstrip at Buna but wrecked two infantry divisions and exhausted two others in the process. The Americans would get a respite for six months to recover. The Japanese did not allow the weary Australians that luxury.

Isolated and weakly protected, the Australian Airbase at Wau seemed like ripe pickings for the Japanese 18th Army. In January,1943, the 102nd Infantry, 51st Division moved by ship to Lae. Although Lae was within range of the allied planes, an overland attack from safer ports further west was impossible because of the dense jungle. Kenney’s ‘Kids’ struck the Japanese convoy again and again, sinking 2 transports and killing 600 Japanese soldiers, under air attack even as they unloaded at Lae only about one third of the force got ashore and they only had about half of their equipment. Even so, these survivors stuck to their orders and on January 30, an attack on the Aussies defending the airstrip. The attack reached the edge of the airstrip, but the reinforced defenders (some running from the transport planes firing at the Japanese) stopped the attack cold. The survivors fell back to Lae.

The Japanese tried to reinforce Lae and from 2-5 March and, in what became known as ‘The Battle of The Bismarck Sea’ the fifth Air Force threw everything it had at the Japanese convoy. On March 2nd, high level B-17’s and B-24’s sank 1 and damaged 2 more, near Lae, the survivors came under attack from B-25’s of the 13th and 90th squadrons. The crews of the B-25’s had been honing their ‘skip bombing’ skills on a derelict ship in Port Moresby harbor and now their practice was being put to the test. The Japanese air patrols were at 7,000 feet and didn’t even see the B-25’s who came roaring in at wavetop height. The newly acquired ‘skip bombing’ skills were put to deadly effect, they sank 8 transports and 4 destroyers. Of the 6,912 men of the 102nd Infantry, about 3,900 survived, but only about 1,000 oil stained, exhausted officers and men reached Lae. Allied fighters strafed the helpless Japanese in the water (a little enterprise started by the Japanese earlier in the war) it was payback time for many of the atrocities committed by the Japanese. The sea turned to bloody froth as sharks swarmed to the feast, allied pilots looked down on hundreds of shattered corpses bobbing about like broken dolls in the bloody swells. This disaster set the seal for the Japanese in New Guinea, from now on the thoroughly demoralized Japanese troops were totally on the defensive, lacking the strength or morale for anything but localized counterattacks.

In an effort to retard the growing allied counteroffensive, the Japanese launched massed air attacks against allied air and shipping around Guadalcanal and New Guinea. 350 naval aircraft attacked in four stages. The inexperienced Japanese pilots gave wildly exagerated reports, claiming 28 transports or warships sunk and 150 allied planes shot down, for only 49 Japanese aircraft lost. In fact the losses were four small ships sunk and twelve aircraft destroyed. A jubilent scheduled a morale raising visit to his front line pilots, but the allies knew the details of the trip after breaking the Japanese code. Orders came from the highest U.S. authority and a flight of P-38 lightnings intercepted and shot down Yamamoto’s plane. So died the great Japanese naval leader who had predicted the defeat of Japan in his ‘sleeping giant’ comments just after Pearl Harbor.

With the death of Yamamoto, so came the death of Japanese hopes for any kind of victory in the South Pacific. The air offensive against Guadalcanal and New Guinea was the last great Japanese air offensive of the South West Pacific area.

The allies next landed at Nassau Bay, after some nigh-time skirmishes the Japanese fled into the jungle. From Nassau Bay, the allies could put pressure on Salamaua, the village that guarded the aproach to Lae, troops were siphoned from Lae to defend Salamaua leaving the Lae garrison vulnerable to flanking attacks from the air and sea. An allied pincer closed on Lae, American troops pushed along the coast from Nassau Bay and Australian troops advanced from Wau. The main Japanese defense was a lone infantry regiment, but in this type of terrain a few determined troops could slow down a force ten times their number. The Americans advancing up the coast had to cross numerous streams, but the Australian line of advance was predictable and the Japanese dug in at various locations. A grueling, 75 day running battle followed, with patrol sized units probing through the undergrowth. Ambush and death awaited the careless or unlucky, in the appalling conditions visibility was often only a few feet into the undergrowth and most deaths were by small arms fire or grenades, emphasizing the close combat conditions.

American losses between the end of June and September 12, when Salamaua fell, were 81 killed and 396 wounded. The Australian Brigade suffered 112 killed, 346 wounded and 12 men missing. Japanese losses were well over 1,000 men. The struggle on New Guinea was fought in some of the worst battle conditions ever encountered, men collapsed from the heat and humidity, soldiers shook constantly from Malaria chills or being drenched in tropical downpours, some simply went mad. The Neuropsychiatric rate for American soldiers was the highest in the South west Pacific theater, 43.94 per 1,000 men. The Japanese soldier had to survive on millet and hard tack. Malnutrition, Amoebic Dysentery, Beri-Beri and Malaria plagued him, rice was an undreamed of luxury, the terrible rations on both sides left the soldiers undernourished and susceptible to uncountable tropical diseases that flourished in the heat and humidity.

The Japanese still had air power on two fronts around the allies, Rabaul and Wewak, Kenney decided to concentrate on Wewak. The distance was to great for allied fighters to escort the bombers and unescorted raids would be suicide, so Kenney had a secret staging base built about 60 miles from Lae. On August 17th, the raid by the 5th Air Force left 100 parked planes destroyed or damaged, a follow up raid the next morning left another 28 Japanese planes wrecked. In two days the Japanese Fourth Air Army had lost three quarters of it’s aircraft. Two weeks later the allies landed just north of Lae, only a few Japanese bombers made any attacks on the beachhead and little damage was done. On September 5th, American Paratroops dropped on Nadzab, twenty miles West of Lae, unchallenged by Japanese aircraft. This move cut of the 51st Division from the rest of Eighteenth Army.

The Japanese had to retreat 50 miles to Finschafen across the 12,000 foot mountain range, of the 8,000 officers and men that started the retreat, about 2,000 were lost in the unforgiving mountains, mostly to starvation. Lt. Gen. Yamada assembled his remaining men on Satelberg ridge which overlooked the entire Finschafen coastline and blocked any further ground push toward Sio.

Australian troops landed at Finschafen on Sept 22nd, after quickly clearing the coastal enclave around the port, they started to push up Satelberg ridge. Against entrenched and fanatical defenders, the Australians soon found themselves embroiled in a series of deadly, small unit combats, that found the 9th Australian Division having to clear isolated pockets of resistance one by one. At least 5,000 Japanese perished, but MacArthur’s expected ‘walkover’ advance was held up for two months.

The allied forces in the Southwest Pacific had increased dramatically, in December, 1942, it was just the 32nd and 41st Infantry Divisions, now there were five divisions, three regimental combat teams, three engineer special brigades, five Australian infantry divisions and three more US divisions on the way. The 5th Air Force had about 1,000 combat aircraft and the 7th fleet increased in size with more transports and landing being added. The Japanese on the other hand, had lost about 3,000 aircraft in the Southwest Pacific and 18th army had suffered about 35,000 casualties, they could not replace these kind of losses.

The jungle that had claimed so many Japanese lives now sheltered them from a concentrated allied ground offensive. Because of the dense jungle, the allies could not mass their overwhelming firepower against any particular stronghold. Of all the allied forces in the area, few actually fought the Japanese, the amount of logistical effort to sustain the allied forces was staggering. To sustain a single infantry regiment in combat required the equivalent of two divisions of supply personnel. Seven out of every eight troops in the area served in support roles, from unloading ships to preventing Malaria, constructing airfields and hauling supplies.

In December, 1943, MacArthur’s forces invaded the southern tip of New Britain, Japanese gunners shot the first wave of the 112th Cavalry to pieces and repulsed the attack. The main force did get ashore, but became bogged down in the swampy ground. On the north side of the island, the attack by the 1st Marine Division ran into similar difficulties, but on a larger scale. An overland advance on Rabaul was impossible. To overcome this obstacle the 126th infantry was shipped from Finschafen to land at Saidor and cut off the Japanese 20th Division who were defending Sio. Again the Japanese were forced to flee through rugged mountains, losing men to starvation and disease all along the trail of retreat.

After an Australian patrol found a complete cypher library for the 20th Division in a stream, Kenney convinced MacArthur that the Japanese had abandoned Los Negros (the largest of the Admiralty Islands, 360 miles from Rabaul) and an invasion force of 1,000 officers and men of the 1st Cavalry Division landed on Los Negros on February 29th. The Japanese were expecting an attack from the opposite direction and were caught by surprise when the 1st landed behind them. Although it was an accident, the good fortune of landing behind the enemy was put to good use and, after some vicious night fighting, the 5th won an impressive victory. Capture of the Admiralties allowed the allies to extend fighter cover beyond Wewak and the decision was taken to make an unprecedented 400 mile leap up the New Guinea coast to Hollandia. The value of the captured cyphers was to make the landing at Hollandia (Operation ‘Reckless’) a masterpiece of planning and ‘Reckless’ would prove to be the turning point in MacArthur’s war against Japan. Through the cyphers it was learned that the planned landing at Hansa Bay would meet strong ground opposition and also the airbase at Hollandia was being ‘beefed up’ to support the land defense of Madang. It was also learned from the cyphers that the land defenses at Hollandia were minimal so ‘Reckless’ was planned and given the go ahead.

Hollandia was still beyond the range of land based fighters, so MacArthur was given three days of carrier fighter support and the invasion of Aitape was planned. By seizing Aitape, land based fighters could support the Hollandia landings and the carrier planes would be used to support the seizing of Aitape. 217 ships transported 80,000 men 1,000 miles to land in three separate areas on Aitape. With the island secure, Kenney was now allowed to crush the aircraft at Hollandia. The Japanese aircrews at Hollandia felt safe from allied aircraft and did not expect the flight of 60 B24’s escorted by P38’s with drop tanks that smashed the airfield at Hollandia on March 30th. Follow up raids demolished nearly all the serviceable Japanese aircraft at Hollandia and never again did the Japanese contest air superiority over New Guinea.

A deception plan kept the Japanese thinking that the next allied landing would be at Hansa Bay, and when the 24th and 41st Infantry Divisions waded ashore at Hollandia they were unopposed. The same thing happened at Aitape, the Japanese Eighteenth Army was isolated in Eastern New Guinea and the Japanese defences had been split.

In order to prevent Adachi’s 18th Army from breaking through the envelopment and also to stop the Japanese defenders from having enough time to regroup and reorganize, the 41st Infantry tried to seize Wadke island and some airstrips at Sarmi on the adjacent New Guinea coast. Wadke was a tough nut to crack, the Japanese had to be winkled out of spider caves, Coconut log bunkers and Coral caves during 2 days of bitter, squad sized actions. Because most of the Japanese defenders had gone to help stave off the Hollandia landings, the Sarmi airfileds were taken with relative ease. In the subsequent push towards Sarmi village, the 6th Division, with the 158th Regimental Combat Team, fought a bitter battle to clear ‘Lone Tree Hill’ of the enemy. The Americans suffered 2,299 casualties (437 killed) while the Japanese had a staggering 4,000 killed.

With all these major operations going on at the same time, the allies now turned their attention to Biak. Biak dominates Geelvink Bay and with it’s capacity for heavy bombers on it’s airstrips it was a powerful lure to MacArthur and Kenney. The 41st Infantry now turned it’s attention to Biak, landing there on May 27th, 1944. Being only 60 miles south of the Equator, the steaming heat combined with sudden Japanese ambushes to make the advance inland very slow indeed. The fighting continued through June and meant that the amphibious fleet along with Kincaid’s 7th fleet were tied up close to Biak and vulnerable to Japanese air and surface attack. The Japanese 16th Cruiser Division tried several attacks on the American ships but thanks to allied code breakers and the 5th Air Force B-25’s, none of them caused any damage and the Japanese lost one Destroyer in the attempts. The Japanese lost about 4,800 men killed defending Biak, American casualties were about 2,800 killed and wounded.

Because the airfields on Biak were not taken on schedule, the allies also attacked the airstrips on Noemfoor island, beginning with a landing on the airfield itself by the 503rd Parachute Regiment. Many Paratroopers had bone-cracking landings as high winds carried them into supply dumps, vehicle parks and wrecked Japanese aircraft. None were actually killed in the jump, but 128 were injured in the jump. 411 Americans were casualties during the battle while about 1,759 Japanese were killed. Although an impressive defensive belt was built around the airstrips, only 3 infantry battalions and 2 under-strength cavalry squadrons guarded the Driniumoor river line. On the night of the 10th of July, 10,000 howling Japanese troops rushed across the shallow Driniumoor and fell upon the vastly outnumbered Americans. Outnumbered and undermanned, the GI’s fired their guns until they were red hot, artillery shells killed and maimed hundreds more Japanese, but the sheer weight of numbers allowed the Japanese to prevail. For a month after, a battle of attrition was waged by small squads of GI’s mopping up the remaining pockets of Japanese. All 10,000 Japanese were killed and about 440 Americans paid the ultimate price. Meanwhile the Australians were advancing towards Wewak in a move that cost them 451 killed while the Japanese lost 7,200! With these horrendous loss ratios (about 23-1 in favor of the allies) the Japanese forces in the South Pacific were chewed up piecemeal and destroyed. About 110,000 Japanese troops died in eastern New Guinea with another 15,000 killed in western New Guinea with another 40,000 isolated there and left to wither on the vine. With the isolation of another 100,000 Japanese troops on New Britain, the totality of the allied victory in the New Guinea campaign came into sharp focus.

The 5th Airforce lost 1374 aircraft from September 1942 to September 1944 and 4,100 airmen killed or missing. 2,000 Australian airmen also lost their lives in the climactic air battles over New Guinea. Before Hollandia it took 20 months and 24,000 allied battle casualties (17,107 being Australian) to advance 900 miles, with another 70,000 Malaria casualties. After Hollandia it took 9,500 casualties (mostly Americans) to leap 1,500 miles in just 100 days. The allies learnt in eastern New Guinea that the terrain dictated the campaign, so in western New Guinea air power and the sea allowed the allies to simply bypass the jungle, seize the coastal enclaves and leave the isolated Japanese troops trapped in the interior, to be decimated by disease and relentless allied pressure.