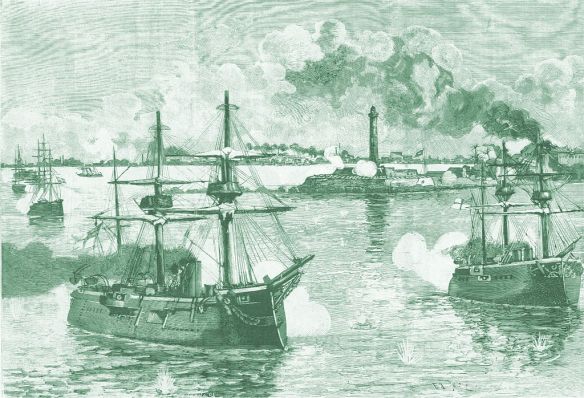

Alexandria, July 11, 1882. The British fleet under the command of Admiral Seymour bombarded the city. Featured warships “Sultan” and “Alexandra”.

The first successful attack by self-propelled torpedoes. The Turkish ship Intibah is destroyed by torpedo boats from Velikiy Knyaz Konstantin torpedo boat tender. A painting by Lev Lagorio.

During 1877–8 the Russians had been providing some torpedo action data during their struggle with the Turks around the Black Sea. The Turkish fleet dominated that sea simply by lying at anchor, as the Russians had no sea-going ironclads and no chance of getting any in while Turkish forts and ships’ guns dominated the narrows to Constantinople; so the Russians had no alternative to using torpedo boats for offensive operations, and they carried out a number of raids by night with specially constructed 15-knot boats some 50 or 60 feet long, carried by mother ships, usually fast merchantmen. However the earlier attacks were made with spar and towing torpedoes, and to get close enough without alerting the enemy with sparks from the funnels and considerable engine noise, they had to drop their speed to walking pace and creep in. Even so they did not escape detection, and were only successful on one occasion when they found the coastal monitor Siefé unprotected by the usual torpedo boat obstructions placed around the Turkish ships. Despite detection by the sentry, they pressed in under her turret guns as they misfired three times and touched a spar torpedo off close by the sternpost; the Siefé sank in a short time. As for the ‘Whitehead’, this was also tried and on one occasion on the night of 25–6 January 1878, the Russians claimed to have sunk a Turkish guard-ship anchored at the entrance to Batum harbour from 80 yards range; although the Turks denied any loss it is possible that this was the first Whitehead success in action. Despite the poor condition of the Turkish fleet and the great resolution of the Russian officers, these were the only effective torpedo attacks of the war. They were modest successes, and it was evident that torpedoes would be little use against an efficient fleet at anchor and guarded as recommended by the British 1875 Torpedo Committee, by nets, lights, Gatling guns and guard boats.

More important than any matériel lessons from the Russo-Turkish war were the strategic issues. Historically Britain’s policy in the eastern Mediterranean had been to support Turkey as a barrier against Russian expansion towards Britain’s Indian Empire and the overland links with that Empire through Mesopotamia or across the sands of Egypt. This policy had been stiffened since 1869 by the opening of the Suez Canal, which seemed to offer French and Russian ships, acting on interior lines from Toulon and the Black Sea, the chance to enter the Indian Ocean and play havoc with all British routes to the East, besides blocking Britain’s own short cut. This was the view of the military departments.

Parallel with this was the strong commercial view: the canal had cut several thousand miles off the routes around the Cape to India and the Far East, and had naturally gathered to itself an increasing volume of steam shipping; by 1875, when Disraeli made his celebrated purchase of Suez Canal shares, over two million tons of British ships were using the waterway every year, 75 per cent of the total traffic. Then, as a symptom of both commercial and military views—or simply as an expression of British expansionist vitality-there was the maritime chauvinist view which by its very nature exaggerated the position; thus The Times could write: ‘The Canal is in fact the sea’; everyone knew who was mistress of the sea! And the Bristol Times and Daily News could go so far as to say, ‘holding that [canal] we hold Turkey and Egypt in the hollow of our hands, and the Mediterranean is an English lake, and the Suez Canal is only another name for the Thames and Mersey.’ In fact the Canal was a part of the Turkish Empire.

When Russia declared war on that Empire in April 1877, Britain was immediately involved, both because there was strong support in the country for the Turks and against the traditional threat to their eastern Empire, and because the Canal, which by now carried three million tons of British shipping a year, might become the scene of warlike operations which would stop commercial traffic. Britain sent a note to Russia, asking her not to ‘blockade or otherwise interfere with the Canal or its approaches’, and moved her Mediterranean ironclad squadron to Port Said.

We don’t want to fight, but by Jingo if we do,

We’ve got the ships, we’ve got the men, we’ve got the money too.

Russia, with her armies fully occupied in a movement around the Black Sea, shortly renounced her belligerent rights against the Canal as an ‘international work’, and agreed to exclude Egypt from her sphere of operations; the following day, as if by reflex, the British squadron weighed and steamed out of Port Said.

The next year, with victorious Russian armies approaching Constantinople Disraeli’s cabinet ordered an even more explicit demonstration: the British ironclad squadron was to steam up the Dardanelles and anchor off the city itself. This was called off temporarily at the request of the Turks who sought an armistice, but was carried out three weeks later while peace terms were being negotiated. It had no effect: Turkey was forced to give up her Balkan Empire to Russian influence, and allow Russia access to the Mediterranean, a defeat for British policy and prestige which threatened war, and a conference was called at Berlin to try and avert it. While preliminary discussions were being held, Disraeli couldn’t resist another naval show: he summoned 8,000 troops from India through the Suez Canal, covered by three ironclads at Port Said, to concentrate at Malta. This was the first time the Indian Army had been used for grand Imperial designs, and while the numbers were not impressive, the manner of their smooth and rapid transfer by water, and the potential of the vast continent they represented, were significant. The Times noted: ‘they revealed England’s capacity for the first time in her history to fight a great Continental war without an ally.’

The actual effect of Disraeli’s demonstration cannot be determined—all parties at Berlin wanted peace—but the upshot was a compromise: Russia gave back to Turkey a great slice of Bulgaria she had acquired at the peace conference, and Disraeli, in a separate convention, took Cyprus from Turkey; he returned to London satisfied that he had brought ‘peace with honour’. Historians have seen in this peace the beginning of an end to the British policy of maintaining the Turkish Empire against Russia at all costs, and—more important for the history of the battleship—the beginning of a new Russian interest in sea power. Four years later they brought out their first systematic naval plan, for 15 battleships, 10 cruisers, later raised to 20 battleships, 24 cruisers, and various smaller craft. The threat of these squadrons in alliance with France provided the main stimulus to British building for the rest of the century.

The same year, 1882, also saw the logical result of Britain’s strategic and commercial interest in the Suez Canal combined with her new-found ‘by jingo’ expansionism; she established military and political control over Egypt. That this happened under a Liberal prime minister, Gladstone, anti-imperial, anti-military, champion of self-determination for all peoples, violent opponent of all that Disraeli had so extravagantly stood for, is an indication of just how inevitable this move was.

It was provoked by a nationalist revolt, itself largely a response to the increasing Europeanization of Egypt since the Canal. When Britain and France sent warships to Alexandria and the Canal to protect their nationals and property and overthrow the nationalist leader, Colonel Arabi, the Egyptian army started throwing up fortifications and mounting guns opposite the ships as they lay at anchor. At which point the French government fell and the new administration, alarmed that the Egyptian crisis might be a sinister German plot to lure French troops from their own borders, recalled their squadrons. Britain was left on her own. Now, while Gladstone was opposed to unilateral action, and tried to seek a solution imposed by the European ‘concert of nations’, he was defeated by his service departments, who took a more practical view after anti-Christian riots and a massacre of 50 foreigners at Alexandria. It became imperative to restore European prestige, and Gladstone sanctioned a naval bombardment of the forts at Alexandria as the quickest and most economical way.

So it was that the first British armoured ships ever to fire their guns in earnest cleared for action on the morning of 11 July 1882, and steamed in to position opposite the forts. They were a diverse collection. Largest and most modern was the Inflexible, commanded by Captain ‘Jackie’ Fisher, a dynamic man already marked for the highest positions; next came the flagship of the Mediterranean station, the Alexandra, the ultimate in British belt-and-battery ships, then the similar Sultan and Superb, and one of the scaled-down versions, the Invincible, to which the commander-in-chief had transferred his flag because of her shallower draft; then there was the Temeraire with her unique arrangement of central battery and disappearing guns at either end above, and finally of the big ships, Reed’s double-turret, fully-rigged, Monarch. There were in addition one smaller ironclad and a number of gunboats. In all, the fleet mounted 43 heavy rifled muzzle-loaders on any one broadside, ranging from the Inflexible’s four 80-ton pieces down to 9-tonners.

Against them the forts mounted only 41 rifled muzzle-loaders, besides 211 obsolete smooth-bores which were little use against armoured ships. Nevertheless, if these batteries had been manned by skilled guns’ crews they would have had all the theoretical advantages: they had steady platforms not deranged by other guns firing alongside, their guns could be set accurately for distance, their shot could be ‘spotted’ on to target by the high splashes it made in the water, and they had the whole of a ship to aim at and damage while a ship had to make a direct hit on a gun or its embrasure to put it out of action.

The theoretical odds didn’t worry the British; it was a bright, clear morning, the sea barely rippled by an offshore breeze, and the guns’ crews, stripped to the waist as in the old days, were eager to give what they considered an Arab rabble a taste of British powder. As the Invincible made the signal for general action a rumble like thunder spread through the separate detachments opposite the forts, and great clouds of thick, white smoke burst from the black hulls of the ships, rising and hanging about the taut rigging, only dispersing slowly. Below, the loading numbers went through their heavy precision drill, now spiced with the urgency of real action.

Again and again, from the smaller calibres first, came ‘the full-toned bellow of an old-fashioned muzzle-loader’, then more dense smoke as the pieces slid back. In the tops officers peered through it to watch the shells rising and growing smaller towards the dun shore some 1,500 yards away, then reported where they landed to the officers of the quarters. Punctuating the continuous thud and chatter came the great concussion of the Inflexible’s turret guns followed by a rumbling sound as the great shells ‘wobbled in the air with a noise like that of a distant train’.

So it went through the glistening day in almost target practice conditions; at one stage when the splashes from the Egyptian shells moved too close it became necessary for some ships to shift themselves with springs from the anchor cables, and for others to weigh and steam to and fro, but the Egyptian reply was not enough to divert the guns’ crews. And gradually the sheer volume of ships’ fire, the exploding shells, the noise and the occasional direct hit which wiped out a gun and its crew, wore the defenders down. Having suffered some 550 killed and wounded, against only 53 British casualties, they evacuated the forts after dark and the sailors and marines walked in on the thirteenth.

They found only 15 of the rifles and nine of the smooth bores disabled by hits from the 1,750 heavy shells, 1,730 lighter shells and 16,000 Nordenfelt bullets fired, and only about 5 per cent of the fire had actually hit the target area, the parapets of the forts. The best shooting appeared to have been made by the two ships with hydraulic laying and training gear, the Inflexible and Temeraire; however, most of the guns of the fleet had mechanical elevating gear and this had proved too slow and clumsy for the smooth water conditions at Alexandria. Had there been any swell the gunlayers could have set the elevation and waited until the ship rolled the sights on target; lacking such customary help one ship at least had bodies of men moving from one side of the deck to the other to produce an artificial roll. The report from the captain of the Monarch illustrates some of the difficulties:

After the captain of the turret had ascertained and communicated the heel to the numbers laying the gun, the time necessarily taken to work the elevating gear, lay the guns by means of the crude wooden scales and make ready is so great that probably another gun or turret will have fired in the interim, and consequently the heel of the ship will be so affected that a relay of the gun is necessary unless a bad or chance shot is purposely delivered.

In addition, there were no more aids to fire control than there had been at the beginning of the century, when effective range had been 300 yards or less; there were no rangefinders, no telegraphs to pass orders or range corrections from the officers stationed aloft to watch the fall of shot, and messages passed by voicepipe were frequently inaudible in the din of battle. The giant products of the ordnance revolution had outgrown the methods of controlling them; had the bombardment of Alexandria failed it is just possible that this lesson might have been heeded, but as the firing had been infinitely better than the Egyptians’, and the victory had been clear-cut and most economical, the reports were filed and there is no evidence that any improvements followed.

The evacuation of the forts took the fighting and destruction into Alexandria itself, hardened the Egyptians behind Arabi and boosted the military and colonial departments in England, whose Cabinet representatives virtually took over from Gladstone and forced him to alter the emphasis of the campaign from a limited punitive demonstration by the Navy to a full-scale invasion by the Army. When the French again refused to co-operate unless the security of the Canal were threatened the British cabinet called in Indian troops; meantime a British admiral who had won a VC in the Crimean War for refusing orders to retreat, ignored instructions to wait for the troops, seized and held Suez with his own squadron, and unilaterally closed the canal. Next month the British army annihilated Arabi’s forces at Tel-el-Kebir, and Britain became sole master of Egypt. The Canal had become at last (almost) as British as the Thames and the Mersey.

These events in the eastern Mediterranean from 1877–82 illustrate the importance Britain attached to command in that sea and over Egypt, a vital link of Empire. This feeling, practical or paranoic depending upon viewpoint, was a major factor behind ironclad, or as they came to be known battleship, building programmes to the end of the century. The scale of these programmes was determined by Russian and French building which, at least in the former case, stemmed directly from the arrogant displays of British naval supremacy. It was well enough for British first lords and naval historians after this to complain that Russia was a ‘land power’ with scarcely any sea trade and therefore no need for a navy, but it was a remarkably one-sided view which expected any great power to take humiliations lying down. On the other hand British interests in the area seemed to practical men in England to demand protection: besides the four million tons of merchant shipping passing through Suez annually by 1882—over 80 per cent of total traffic—and the British investment in the area, there was the awful possibility of such a vital hinge of maritime strategy falling to France or Russia. In this sense the acquisition of real power in Egypt was a natural development of the policy or instinct which had given Britain chains of island and mainland bases from which to protect her shipping throughout the world. The flag had to follow trade.

Whether the Egyptian move was an essential consequence of maritime strategy, or a high-handed demonstration of naval power, or both of these and a bit of the bond-holder’s dilemma, whether it was part reaction to France’s pretensions to a North African empire or was itself powerful stimulus to European powers to carve up bits of the undeveloped world for themselves—as they did with increased frenzy during the following decades—for the purposes of this story it was provocation for a naval race. It not only upset the balance at the meeting point of East and West and extended Britain’s naval commitments, it provided France and Russia with sufficient envy and resentment to begin building programmes which might—at least in alliance—prevent future unilateral action by the ‘mistress of the seas’.