Planks Pegged And Sewn

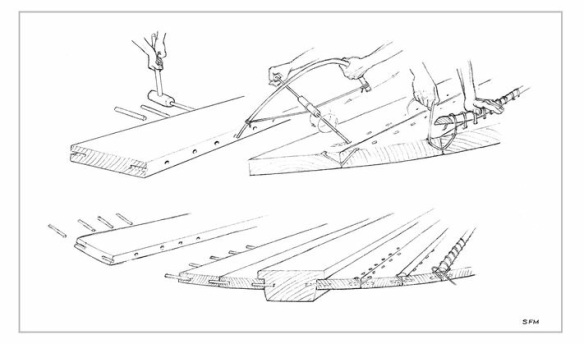

The system of construction made a strong hull that could withstand severe shocks. Only after the hull was pegged and stitched with linen—or, as an Athenian would have said, gomphatos and linorraphos—did the builder insert the curving wooden ribs. And should a rock or an enemy ram punch a hole through the planking, a wooden patch could be quickly stitched into place to close the breach.

On top of the long slender hull the shipwright now erected the structure that set Greek triremes apart from their Phoenician counterparts: the wooden rowing frame or parexeiresia (that is, a thing that is “beyond and outside the rowing”). Sometimes referred to as an outrigger, the rowing frame was wider than the ship’s hull and in fact performed multiple functions.

First, the rowing frame carried the tholepins for the upper tier or thranite of oars, and its wide span allowed for a long rowing stroke. Second, side screens would be fastened to the rowing frame when the ship went into battle to protect the thranite rowers from enemy darts and arrows. And third, the top of the frame could support a covering of canvas or wood. On fast triremes such as Themistocles had ordered, white linen canvas was spread above the crew to screen them from the hot sun while rowing. On a heavy trireme or troop carrier, wooden planking would be laid down on top of the rowing frame to make a deck on which soldiers or equipment could be transported. Finally, the stout transverse beams that crossed the ship at the end of the rowing frame served as towing bars to tow wrecked ships or prizes back to shore after a battle.

As the great size of the rowing frame suggests, oars were the prime movers of the trireme. At two hundred per ship (a total that included thirty spares), Themistocles’ new fleet required twenty thousand lengths of fine quality fir wood for its oars. The long shaft had a broad, smoothly planed blade at one end, and at the other the handle ended in a round knob to accommodate the rower’s grip. One man pulled each oar, securing the shaft to the upright tholepin with a loop of rope or leather. The 62 thranite oarsmen on the top tier enjoyed the most prestige. Inboard and below them were placed the wooden thwarts or seats for the 54 zygian oarsmen and the 54 thalamians. The latter took their name from the ship’s thalamos or hold since they were entombed deep within the hull, only a little above the waterline. All the rowers faced aft toward the steersman as they pulled their oars.

Once all these wooden fittings of the hull were complete, it was time to coat the ship with pitch, an extract from the trunks and roots of conifers. Once a year pitch-makers tapped or stripped the resinous wood of mature trees. In emergencies they cut down the firs and applied fire to the logs, rendering out large pools of pitch in just a couple of days. Carters conveyed thousands of jars of pitch to the shipbuilding sites in their wagons. The poetical references to “dark ships” or “black ships” referred to the coating of pitch.

More than hostile rams or hidden reefs, the shipwrights feared the teredon or borer. Infestations of this remorseless mollusk could be kept at bay only by vigilant maintenance, including drying the hull on shore and applications of pitch. In summer the seas around Greece seethed with the spawn of the teredo, sometimes called the “shipworm.” Each tiny larva swam about in search of timber: driftwood, dock pilings, or a passing ship. Once fastened to a wooden surface, it quickly bored a hole by wielding the razorlike edge of its vestigial shell as a rasp. From that hiding place the teredo would never emerge. Once inside the hole it kept its mouth fixed to the opening so as to suck in the life-giving seawater. The sharp shell at the other end of the teredo’s body continued to burrow deeper. As the burrow extended into the timber, the animal grew to fill its ever-lengthening home.

Within a month the sluglike teredo could reach a foot in length. Now it was ready to eject swarms of its own larvae into the sea, starting a new cycle. Once planking and ribs were riddled with their holes, a ship might suddenly break up and sink in midvoyage. Even when a wreck reached the bottom of the sea, the teredo would continue its attacks. In a short time no exposed wood whatever would be left to mark the ship’s resting place. Through conscientious maintenance—new applications of pitch, drying out and inspection of the hulls, and prompt replacement of unsound planks—an Athenian trireme could remain in active service for twenty-five years.

The trireme’s design approached the physical limits of lightness and slenderness combined with maximum length. So extreme was the design that not even the thousands of wooden pegs and linen stitches could prevent the hull from sagging or twisting under the stresses of rough seas or even routine rowing. On Athenian triremes huge hypozomata or girding cables provided the tensile strength that the wooden structure lacked. A girding cable weighed about 250 pounds and measured about 300 feet in length. Each ship carried two pairs. Looped to the hull at prow and stern, the cables stretched around the full length of the hull below the rowing frame. The ends passed inside where the mariners kept them taut by twisting spindles or winches. Just as pegs and linen cords formed the joints of the hull, the girding cables acted as the ship’s tendons.

The trireme required many other ropes as well. Made of papyrus, esparto grass, hemp, or linen, ropes supplied the rigging for the mast and sail, the two anchor lines, the mooring lines, and the towing cables. The ship’s tall mast and the wide-reaching yards or yardarms that held the sail were made from lengths of unblemished pine or fir. For the sail, the women of Athens wove long bolts of linen cloth on their upright looms. Sailmakers then stitched many such bolts together into a big rectangle. Despite their great weight—and their great cost—the mast and sail were secondary to the oars and, when battled threatened, were removed from the ship altogether and left on shore. Some triremes also carried a smaller “boat sail” and mast for emergencies.

The ship’s beak had already been fashioned in wood as part of the hull. To complete the trireme’s prime lethal weapon, the ram, metalworkers had to sheathe the beak with bronze. The one hundred rams needed for Themistocles’ triremes required tons of metal—a gigantic windfall for the bronze industry. Bronze, an alloy of nine parts copper to one part tin, does not rust and is more suitable than iron for use at sea. Some of the bronze poured into the rams of the Athenian triremes was recycled, melted down from swords that had been wielded in forgotten battles, from keys to vanished storerooms, images of lost gods, and ornaments of beautiful women long dead. Master craftsmen made the rams with the same lost-wax method that they used to cast hollow bronze statues of gods and heroes for the temples and sanctuaries.

The form of the ram was first modeled in sheets of beeswax directly onto the wooden beak, so that each would be custom made for its ship. As the artists worked the wax onto the beak, it warmed up and softened, becoming easier to handle. At the ram’s forward end the wax was built up into a thick projecting flange, triple-pronged like Poseidon’s trident. When every detail of the ram had been modeled, the wax sheath was gently detached from the wood and carried over to a pit dug in the sand of the beach.

The next step called for clay, the same iron-rich clay that went into Athens’ red and black pottery. With the wax model turned nose downward in the pit, clay was packed around its exterior and into its conical hollow to create a mold. Thin iron rods forged by the blacksmiths were pushed through the wax and the two masses of clay. When the wax was entirely encased in the clay except for its upper edge, the massive mold was inverted and suspended over a fire until all the wax was melted out. A hollow negative space in the exact shape of the ram had now been formed inside the packed clay. It remained only to fill the mold with molten bronze. But this was a complex and difficult undertaking.

Wood fires could not produce the necessary heat; the process required charcoal. A trireme’s ram had to be cast in a single rapid operation. First the bronze workers erected a circle of small upright clay furnaces around the rim of the pit. A channel led from the foot of each furnace to the edge of the mold. Broken bronze, whether from ingots or scrap, was divided among the furnaces. With the lighting of the charcoal, the metal in each furnace quickly became a glowing, molten mass. At a signal, the bronze workers and their apprentices removed the clay stoppers from all the furnaces. Simultaneously the bright hot streams poured down the channels and filled the hollow in the clay mold left by the melting of the wax. The casting happened with a rush, and the bronze cooled and hardened quickly. When the clay mold was broken (never to be used again), the bronze ram itself, smooth, dark, and deadly, saw the light for the first time. After cutting away the iron rods, finishing off the back edge, and polishing the surface, the bronze workers slid the new ram into place over the trireme’s wooden beak, fastening it securely with bronze nails.

Quarrymen and stone workers provided fine white marble from Mount Pentelicus near the city, and from thin slabs of this marble the sculptors carved a pair of ophthalmoi or “eyes” for each trireme. A colored circle painted in red ochre represented the iris. The eyes were fixed on either side of the prow. Athenians believed that these eyes allowed the ship to find a safe passage through the sea, completing the magical creation of a living thing from inanimate materials. In Greek terminology, the projecting ends of the transverse beam above the eyes were the ship’s ears, and the yardarms were its horns; the sail and banks of oars were its wings, and the grappling hooks were its iron hands.

Blacksmiths fashioned a pair of iron anchors for each trireme, to be slung on either side of the bow. They would prevent the ship from swinging while its stern was grounded on the beach. Tanners and leatherworkers provided the tubular sleeves that waterproofed the lower oar ports. From the same workshops came the side screens of hide for the rowing frames. Pads of sheepskin would enable the trireme’s oarsmen to work their legs as they rowed, thus adding to the power of each stroke.

Finally goldsmiths gilded the figurehead of Athena that would identify each ship as a trireme of Athens. The goddess wore a helmet as well as the famous breastplate or aegis adorned with the head of Medusa, the gorgon that could turn a mortal to stone with a single glance. As patron deity of arts and crafts, a goddess of wisdom and also of war, Athena had been presiding over the entire project from beginning to end.

From the mines of Laurium the silver had flowed through the city’s mint, where it was transformed into the coins that bore the emblems of Athena. Then as Themistocles had planned, the river of silver broke into a hundred separate streams, passing through the hands of the wealthy citizens who organized the great shipbuilding campaign. During the months of shipbuilding the silver was disbursed to all those workers, from loggers to shipwrights to bronzesmiths, whose efforts made Themistocles’ vision a reality. In the end, the money returned to many of the same citizens who had voted to give up their ten drachmas for the common good. By the time one hundred new triremes gleamed in the sunlight at Phaleron Bay, the Athenians were already a changed people. In the great contest that lay ahead, as they hazarded their new ships and their very existence in the cause of freedom, their sense of common purpose would grow stronger with every trial and danger.