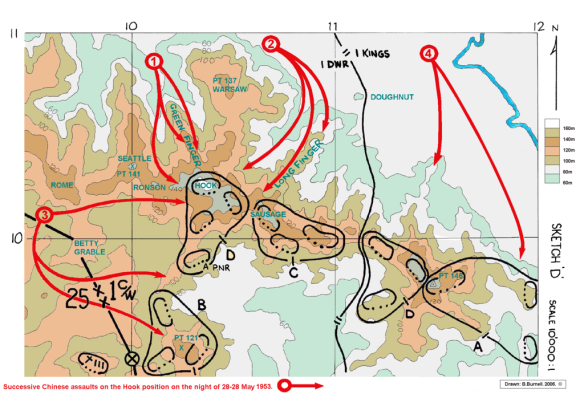

Successive Chinese assaults on the Hook position defended by the 1st Battalion, The Duke of Wellington’s Regiment on the night of 28 May 1953. The fourth Chinese assault on the right flank of 1 battalion, the Duke of Wellington’s was repulsed by the 1st Battalion, The King’s Regiment, with the aid of artillery support.

Men of the 1st Battalion, The Duke of Wellington’s Regiment, have a smoke while waiting for dusk to fall before joining a patrol into no-man’s land at The Hook.

On 25 May 1953, the Chinese struck for the last time.

For years now there had been periods of alternative stalemate, interspersed by those of brief, bitter and very bloody fighting. Still the Chinese came in ‘waves’ or ‘human waves’, as the Tokyo feather merchants called what seemed the enemy’s inexhaustible supply of manpower. Indeed the outposts on the heights of Southern Korea from which the Allies fought stank, as one GI put it, of ‘flies, rats, garbage, fecal waste’…with the ‘worst job covering the Chinese bodies that lay everywhere on the side of the hills’.

The British of what was now the ‘Commonwealth Division’ played their role in those bloody skirmishes, which sometimes developed into outright battles. One after another the first battalions of these infantry regiments, which have now long disappeared, took their place in the line In Korea. They fought their private battle, tended their wounded, buried their death and vanished thereupon into the obscurity of that ‘forgotten war’. The Royal Warwicks, the Royal Irish Fusiliers, the Royal Sussex, the Cameron Highlanders, the Essex Regiment…they were all there, fighting to gain ‘honours’ the glory of which has faded over the years. In that last spring of the Korean War it was the turn of that regiment bearing the name of the most famous soldier the British Army has ever produced — the 1st Duke of Wellington’s Regiment.

The position they would defend was the notorious ‘Hook’, part of that range ‘Old Baldy’, ‘Pork Chop Hill’ which would go down in the folklore of the US Army afterwards.

The battle for the ‘Hook’ had commenced back in October 1952 when the 7th US Marines had fought a successful defensive action on those grim, barren, shell-pitted heights. Thereafter, the position had fallen into the care of the British Commonwealth Division. Again it tempted the communists into attacking it, for as one of the officers of the Duke of Wellingtons said later: ‘It was a sore thumb, bang in the middle of Genghis Khan’s old route into Korea…it commanded an enormous amount of ground.’

On 18 November 1952, it was the turn of the 1st Black Watch. Again the Chinese attacked in their usual wasteful manner; but then, they had the men. Human life didn’t count for much in that huge country with its tremendous population. Nor were the Jocks inclined to take the Chinkies prisoner. Twice the Chinese attempted to swamp the Black Watch positions and twice they were forced back. At tremendous cost they failed to shift the men of Scotland’s elite regiment.

However, the British casualties as well were mounting in the defence of the ‘Hook’ — indeed the Army lost more on the height’s steep flanks than in any other battlefield in the three-year struggle for Korea. Now they were going to lose some more — but they would never lose the ‘Hook’.

On the night of 28 May, 1953, the ‘Dukes’ were warned by the urgent brassy blare of bugles that a Chinese attack on the ‘Hook’ was imminent. As the sound died away, there was the first obscene thump and whack of mortars being fired. To the defenders’ front, cherry-red flames erupted everywhere as the Chinese artillery joined in. The Chinese were coming!

‘Stand to,’ the NCOs and officers yelled urgently. Men grabbed their equipment and sprang to the fire-steps of their deep weapon pits. They slammed the brass-clad butts of their rifles and Brens into their shoulders. Others placed their grenades, already primed, in handy little holes in the sides of the slit trenches. The fire swept over them in fiery fury. Now they could hear the commands, the shouts, the angry orders coming from below. The Chinese were attacking in strength. As all around them their trenches started to crumple under a series of direct hits, the defenders began to fire furiously into the darkness.

Both dug-in Centurion tanks being used to support the Dukes with their 20-pounder cannon were hit. A half-blinded young officer just out of Sandhurst staggered bleeding into his company commander’s dug-out. He reported that his position was ‘untenable’. ‘Balls,’ his company commander snapped curtly, ‘get back!’ A Browning machine-gun was knocked out, with five killed and three wounded. Another machine-gun took up the challenge. The Chinese fell everywhere. The night was hideous with their screams and yells of pain. Still they kept on coming — and the Dukes kept on mercilessly mowing them down.

Now the Chinese had in places reached the summit. The Dukes went underground in their tunnels. By this time their wireless sets were smashed, so they were cut off from Brigade and had to rely on themselves. They did, fighting back with the desperate courage of men who knew instinctively that they either fought and won — or died. Underground the Chinks would show no mercy. It had become a close-combat battle in which no such mercy was shown or expected.

Commanding the Dukes’ Support Company, Maj Kershaw (who had missed out on most of the Second World War because he had been stationed in Iceland and other out-of-the-way places) was now getting his ‘bellyful’ of hand-to-hand combat. He had already fought his way into a tunnel until it too had been swamped by the enemy. A Chinese only feet away threw a stun grenade. He yelped with pain, as his legs and buttocks were peppered with fragments, the blast knocking his helmet off and his Sten gun out of his hands.

He staggered somehow into another trench. Four wounded Korean ‘Dukes’ lay in it. Half blinded and threatening to drift into unconsciousness at any moment, he tied a tourniquet with his bootlace. Still he fought back, until the Chinese blew in the entrance to the tunnel.

A Corporal Walker ran with his hard-pressed section into another tunnel. Again the enemy were everywhere. While his men frantically barricaded themselves in, the young corporal fired rapid bursts to keep the enemy at bay. The Chinese retaliated by tossing in satchel charges whose blast slapped the defenders around the faces, buffeting them time after time and almost deafening them. More critically, it blocked the entrance and thus it was that, when they had recovered from the explosion, they found themselves gasping for air like ancient asthmatics in the throes of an attack.

They lay ‘doggo’ and, as Walker related later, they heard the Chinese demand in English, ‘Where your friends?’ Private Smith, helpless after having been wounded in both legs, lied weakly, ‘They’re not in this tunnel,’ he gasped.

Walker pulled himself together. He advanced through the darkness further up the tunnel, heart beating furiously, weapon at the ready. He saw torches approaching. He knew instinctively they could belong only to the Chinks. He didn’t wait to find out whether his guess was right, but loosed off a burst. In the confines of the tunnel, the racket was ear-splitting, giving way to screams and yelps of pain. Then a loud echoing silence. Not for long. A rumble, a trembling, and the Chinese detonated a charge at the entrance. ‘They were scaled in the tunnel, as if in their own tomb. ‘We were in darkness,’ as Walker afterwards remembered that terribly long night, ‘and choking through dust and lack of air. One chap alone had half a bottle of water and he shared it all round, all getting a lick every hour.’

Maj Lewis Kershaw — trapped, bleeding badly and half-conscious in his tunnel — held the survivors entombed there together with his undaunted spirit. ‘The Dukes don’t die,’ he shouted defiantly; ‘Stick it!’ And stick it the survivors of the 1st Battalion the Duke of Wellington’s Regiment did. When on the next day the rescue parties broke through to the trapped men, Lewis Kershaw was still in command! Blinking in the grey light of the new day, he ordered them, ‘See that I am the last out!’ It was only then that he allowed himself to finally pass into the boon of unconsciousness.

All that long night and the following day, the Chinese attacked and attacked with savage fury. The British brought down artillery on their positions. Later it was discovered that a whole battalion of Chinese infantry had been wiped out in the course of that suicidal barrage. Their shattered bodies hung from the wire everywhere like bundles of blood-red rags.

But the Dukes didn’t only defend, they counter-attacked. Over the previous years the Dukes had always prided themselves on having the best rugby team in the whole of the British Army. Some of the players were indeed international stars. Now one of them, six foot four Campbell-Lamerton, led his company into the attack to regain ground lost by the Dukes. It was a matter of honour. It was tough going. The day-long artillery bombardments, British and Chinese, had ‘literally changed the shape’ of the top of the Hook. Rubble and tangled smashed wire — and the enemy — made progress damnably slow, but somehow they did it. At 3.30 on the morning of 29 May, the attackers reported that the Hook was again in the hands of the Dukes. Virtutis fortutia comes (motto of the Duke of Wellingtons) — Fortune had indeed favoured the Brave…

As the dawn light came slowly that morning over the shattered lunar landscape, as if some deity were reluctant to illuminate the ugliness below, the search parties started to stumble through the smoking wreckage of the Dukes’ positions to recover the casualties. They found 250 dead and 800 wounded Chinese. Of the Dukes some 149 had been killed, wounded and captured (many of the sixteen POWs wounded, too). In a matter of a day, the Duke of Wellingtons had lost one-fifth of its strength.

Brig Kendrew of the brigade to which the Dukes belonged came up to the Hook to see what had happened. Kendrew had seen much of war and had won three DSOs in the Second World War, but even so he was shocked. Grave-faced and shaken, he said, ‘My God, those Dukes! They were marvellous. In the whole of the last war I never knew anything like that bombardment. But they held the Hook…I knew they would…’

Despite the praise, the Brigadier could see they’d had enough. Besides, most of their positions and many of their weapons had been shattered. He ordered the Battalion relieved at once. If the Chinese attacked again, they would be in a damned difficult position, so he commanded the 1st Royal Fusiliers to take over. At noon, long lines of Fusiliers started to wind their way up the heights, including an obscure cockney one day to be known to the world as Michael Caine, actor. ‘What’s been going on?’ one of the Fusiliers asked as he came level with the Dukes and saw the carnage and wreckage. The unknown Duke had his answer ready. Calmly but proudly, he answered: ‘Just seeing off a few Chinks…’

#

And so they had. The Dukes, three-quarters of them national servicemen who were paid £1.62 a week by a grateful country for risking their lives, had fought the British Army’s last real battle of the Korean War. It went on for several more weeks, but in the end the Chinese knew they’d never defeat the Allies now. They asked for a truce.

In July 1953 they waited as the final hours ticked away, as had happened in Europe when the armies there had waited for the 11th hour of the 11th day of the 11th month of 1918 till that year’s Armistice was to come into force. Right up to the last moment on that Monday 27 July, the guns thundered. Half an hour after the last bomb had been dropped by the US Air Force, Gen Trudeau of the US 7th Infantry Division pulled the lanyard of one of the divisional artillery pieces and fired the last round. He kept the shell case and was quoted as saying later: ‘I was happy it was over.

It was apparent that all we were going to do was to sit there and hold positions. There wasn’t going to be any victory.’

The General was right: there wasn’t! What he apparently didn’t realize at the time was that it was not a question of a US victory, but rather of defeat or at the best stalemate. In essence the United States of America, one day to be seen as the world’s superpower, had lost its first war…

Not that the GIs cared. They ‘partied’. If they were lucky they got high on hooch and local rice wine. If they weren’t they let off rockets and signal flares. The US Marines who had suffered so much in Korea sang dirty songs and told tall tales. One GI seemed to sum up the prevailing mood among the men. Pte Bill Shirk maintained it had all been a ‘hell of a waste’. ‘Who gives a shit if they’re North Korean or South Korean? You can’t take a person living like an animal and expect him to act like a human being.’

Perhaps his view was typical. They were all gooks anyway. But whatever the men ‘at the sharp end’ thought it really didn’t matter on that wonderful July day. The war was over, so they celebrated.

As for the British, nothing much is recorded (as was customary in Korea) of their reaction. More than likely, being the British Army, they were given a couple of bottles of cheap Jap beer and then told to ‘bull up’. As they always maintained in the ‘Kate Ramey’ — ‘war is hell, but peacetime will kill you…’