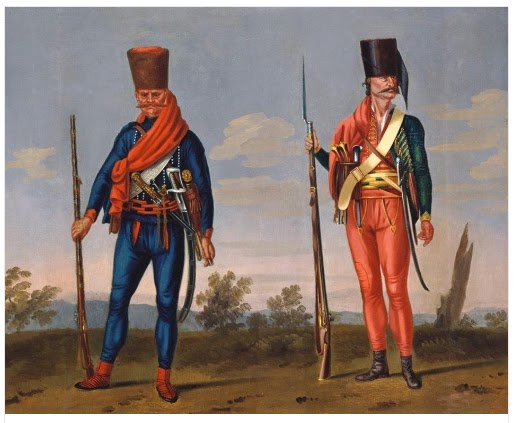

Bannalist and Pandour, Freikorps Trenck. By Morier, 1743.

As well as the Hungarians there came another group of volunteers: the Pandours. These brigands, often the natives of the ‘wrong side’ of the Military Frontier, followed their leader, the gifted Baron Trenck. This Trenck is not to be confused with his kinsman who was initially in the Prussian service and whose memoirs were widely read in the eighteenth century. The Austrian Trenck pledged a unit of irregulars, a Freikorps (Free Corps) numbering about 1,000 to Maria Theresa’s aid.

These irregulars were welcomed into the Imperial service even though they possessed no conventional officer corps but a system whereby each unit of fifty men obeyed a ‘Harumbascha’. All the Pandours, Harumbaschas included, were paid 6 kreutzer a day out of Trenck’s own estates, a pitiful sum. This was certainly not enough for any semblance of a uniform and their appearance was highly exotic. When they appeared in Vienna at the end of May 1741, the ‘Wienerische Diarium’ could write:

Two Battalions of regular infantry lined up to parade as the Pandours entered the city. The Irregulars greeted the regulars with long drum rolls on long Turkish drums. They bore no colours but were attired in picturesque oriental garments from which protruded pistols, knives and other weapons. The Empress ordered twelve of the tallest to be invited with their officer to her Ante-Room where they were paraded in front of the dowager Empress Christina.

Neipperg found the Pandours rather raw meat. He was unused to the ways of the Military Frontier. On several occasions while campaigning he had to remind them that they were ‘here to kill the enemy not to plunder the civilian population’. The Pandour excesses soon provoked Neipperg into attempting to replace Trenck. The man chosen for this daunting task was a Major Mentzel who had seen service in Russia and was therefore deemed to be familiar with the ‘barbaric’ ways of the Pandours. Unfortunately, some Pandours fell upon Mentzel as soon as news of his appointment was announced and the hapless Major only escaped with his life after the intervention of several senior Harumbaschas and Austrian officers.

Mentzel, notwithstanding this indignity, was formally proclaimed commander of the Pandours, whereupon a mutiny took place which only Khevenhueller, a man of the Austrian south and therefore familiar with Slavic methods, could stem by reinstating Trenck under his personal command. At both Steyr and Linz, the Pandours in their colourful dress decorated with heart-shaped badges and Turkic headdresses would distinguish themselvesagainst the Bavarians. Indeed, by the middle of 1742 the mention of their name alone was enough to clear the terrain of faint-hearted opponents. Within five years they would be incorporated into the regular army though with an order of precedence on Maria Theresa’s specific instruction ‘naturally after that of my Regular infantry regiments’. At Budweis (Budejovice) they captured ten Prussian standards and four guns.

The crisis was far from over. While Khevenhueller prepared a force to defend Vienna, the Bavarians gave the Austrian capital some respite by turning north from Upper Austria and invading Bohemia. By November, joined by French and Saxon troops, this force surprised the Prague garrison of some 3,000 men under General Ogilvy and stormed into the city largely unopposed on the night of 25 November. To deal with these new threats, Maria Theresa using Neipperg as her plenipotentiary had signed an armistice with Frederick at Klein Schnellendorf. She realised that her armies were in no condition to fight Bavarians, Saxons, French and Prussians simultaneously.

Maria Theresa received the news of Prague’s surrender with redoubled determination. In a letter to Kinsky, her Bohemian Chancellor she insisted: ‘I must have Grund and Boden and to this end I shall have all my armies, all my Hungarians killed off before I cede so much as an inch of ground.’

Charles Albert the Elector of Bavaria rubbed salt into the wounds by crowning himself King of Bohemia and thus eligible to be elected Holy Roman Emperor. The dismemberment of the Habsburg Empire was entering a new and deadly phase. Maria Theresa was now only Archduchess of Austria and ‘King’ of Hungary.

The election of a non-Habsburg ‘Emperor’ immediately provided a practical challenge for the Habsburg forces on the battlefield. Their opponents were swift to put the famous twin-headed eagle of the Holy Roman Empire on their standards. To avoid confusion Maria Theresa ordered its ‘temporary’ removal from her own army’s standards. The Imperial eagle with its two heads vanished from the standards of Maria Theresa’s infantry to be replaced on both sides of the flag with a bold image of the Madonna, an inspired choice, uniting as it did the Mother of Austria with the Mother of Christ and so investing the ‘Mater Castrorum’ with all the divine prestige and purity of motive of the Virgin Mary.

Another development followed: because Maria Theresa’s forces could no longer be designated ‘Imperial’ there emerged the concept of a royal Bohemian and Hungarian army which became increasingly referred to for simplicity’s sake as ‘Austrian’. The name would stick. When less than five years later Maria Theresa’s husband was crowned Holy Roman Emperor, Europe had become accustomed to referring to the Habsburg armies as the Austrians.

A glimmer of hope appeared as Khevenhueller cleared Upper Austria of the Bavarians and French. He blockaded Linz, which was held by 10,000 French troops under Ségur. And by seizing Scharding on the Inn he deprived the unfortunate French garrison of all chance of relief from Bavaria. The Tyroleans showed their skill at mountain warfare and ambushed one Bavarian force after another, inflicting fearful casualties. On the day that Charles Albert of Bavaria was elected Holy Roman Emperor, Khevenhueller sent the Bavarian upstart an unequivocal message: he occupied his home city of Munich and torched his palace.