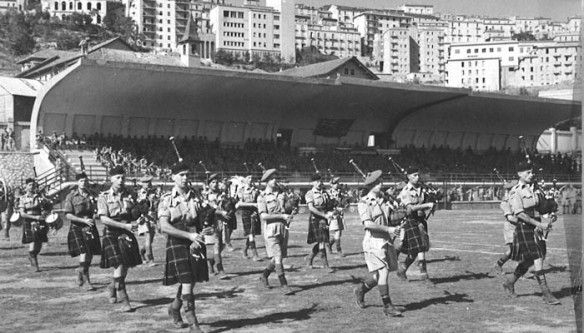

Seaforth Highlanders Pipes and Drums at Catania Stadium, Sicily in August 1943.

British troops in Catania.

The decisions taken by Alexander on 13 and 16 July dictated the form that the campaign would take. By giving Montgomery the use of Highway 124 he had made the Eighth Army the principal agent by which Messina should be captured, and relegated the Seventh to a secondary role. With XIII and XXX Corps advancing on two fronts towards Catania and Enna respectively, the expectation was that Catania would quickly be occupied; but a stalemate developed as the German defences stiffened south of the city. Montgomery’s attempt to broaden his front there by moving 51st (Highland) Division up on the left of XIII Corps, which might have outflanked the enemy, was too late. On 16 July Alexander took the decision to move both of the British corps eastwards – only for them to run directly into the Axis defence line known as the Hauptkampflinie which Kesselring had agreed with Generals Hube and Guzzoni. The Axis forces in Sicily were now, de facto, under the command of the Germans, and General Hube was an effective instrument to carry out their policy – which was not wholly communicated to the Italians – of fighting a defensive battle which would lead to eventual evacuation of the island.

As outlined earlier, on 16 July Hitler ordered further reinforcements into Sicily. The one-armed General der Panzertruppen Hans Valentin Hube’s XIV Panzer Corps Headquarters arrived and took firm control of the German forces, which now included the remainder of 1st Parachute Division (less one regiment), which arrived from Avignon, and much of 29th Panzer Grenadier Division which crossed the Messina Straits from Calabria. The Luftwaffe flak batteries were brought into action as field artillery. Whatever Kesselring may have told Hube about the potential for driving the Allies back into the sea, Hube was clear in his own mind that a progressive withdrawal was the only feasible strategy. He had also received secret orders to keep the Italians out of planning, and was to gain control of all Italian units still in Sicily. His task was to save as many German forces as possible for future operations. By 2 August, Hube would be in control of all Sicilian operations.

Every move that the British made on the Catania Plain could be observed from the slopes of Mount Etna. Hube had sufficient forces to counter any advance XIII Corps could make, but no proper reserves. While 5th and 50th Divisions attempted to progress northwards, the Hermann Göring Division and the Fallschirmjäger dug in firmly.

The first of the defence lines which the Axis command established to protect the withdrawal to the Straits of Messina, the Hauptkampflinie, ran along the route of the road just west of Santo Stefano, south to Nicosia and Agira, then east to Regalbuto before heading south again to Catenanuova, eastwards along the Dittaino River, and ran across the northern edge of the Catania Plain, reaching the coast about six miles south of that city. The line therefore ran all of the way from the northern to the eastern seaboards, taking advantage of the mountainous terrain, a river bank, and the Catania Plain with its broken countryside.

Fifteen miles behind this line the Germans planned the Etna Line, from San Fratello south to Troina and then east to Adrano (which was also known as Aderno in some accounts) and along the road which ran eastwards along the southern edge of Etna to the sea at Acireale. Behind this, the innermost defence line which protected the north-eastern evacuation sites ran from Mount Pelato through Cesaro and Bronte to the sea near Riposto.

The three lines were based on natural features which lent themselves to defence, and which could be strengthened by demolishing roads and bridges and by the laying of minefields and booby-traps. The defences were beginning to be established, albeit not yet firmly, by 17 July. The anchor of the Hauptkampflinie was Catania – and it was here that Montgomery pressed XIII Corps to attack.

Between 16 and 22 July the Axis operations were focused on three, largely independent, areas. In the east, forces largely made up from the Hermann Göring Division held the line of the Dittaino River from Dittaino Station to the sea, forty-two miles to the east and four miles south of Catania. Alongside the Hermann Göring Division were elements of 1st Parachute Division, part of the Livorno Division, and 76 Infantry Regiment from the Napoli Division. Facing them were XIII Corps and 51st Division from XXX Corps.

In the centre of the Axis front, 15th Panzer Grenadier Division was withdrawing from a line which ran through the towns of Caltanissetta, Pietraperzia, Barrafrance, Piazza Armerina, and then north-westwards to the Leonforte-Nicosia area. Here, 1st Canadian Division was in contact with the enemy at the eastern end of the twenty-mile line. At the western end of this sector, 1st (US) and 45th (US) Divisions were in pursuit.

The westernmost section of the Hauptkampflinie was the most fluid. Here the Italian XII Corps, comprising the Assietta and Aosta Divisions, most of the Corps artillery and three Mobile Groups, had been ordered back to defend a forty-five mile length of line on Highway 120 running from Cerda through Petralia to Nicosia. Harassed in their retirement by American troops and aircraft, some of the Italian columns were destroyed as they moved along the narrow roads.

The defence line was very long, and was not continuous. Formations were not firmly linked together, and the forces were thinly stretched; in theory, it should have been possible for attackers to feel out weak spots through which to thrust deep into enemy territory. In practice, however, the terrain dictated otherwise, and the climate did not help. The road-bound Allies were tied to the narrow, winding routes which were frequently even more constrained by the stone walls which bordered them.

The most practical directions along which to advance were generally the most obvious – and the most obvious places to concentrate the defences. The Allies were further hindered by their lack of animal transport. During the planning stages for HUSKY seven companies of pack-mules were included in the Eighth Army’s Order of Battle, but these were not included when priorities were established for shipping men and materiel to Sicily. On 17 July, Eighth Army signalled to Middle East that ‘No Pack Transport Units are required by 8th Army in Sicily’. Although local mule trains were organised, they were too small and too untrained to achieve anything more than small tasks.

From Alexander’s perspective, the Eighth Army appeared to be the formation best situated to achieve the objective of seizing Messina and sealing off the enemy’s escape route. Not only were the British well-positioned – on the map – to push up the eastern coast of Sicily, but there was also the legacy of the performance of the Americans and British in North Africa, which left a lingering mistrust of Seventh Army’s reliability. Alexander had confidence, built upon evidence of past performance, in Montgomery. But Monty’s assertion, on 12 July, that Catania would be in his hands two days later failed to materialise – as did his revised target of reaching the city on the 16th. Alexander’s faith in Montgomery had led him to accept the redefinition of the Anglo-American armies’ boundary; the failure to push 45th (US) Division rapidly northwards on Highway 112 had cost him the opportunity to split Sicily in two quickly and to forestall the Germans’ window of opportunity to inject fresh forces into the island and to stabilise their defence lines.

Montgomery’s strategy, accepted by Alexander, effectively sent the Eighth Army in diverging directions to objectives forty-five miles apart – XIII Corps towards Catania, and XXX Corps towards Enna – while the American Seventh Army was left without a real role in achieving the objective of securing Messina, other than protecting the British left flank. As the Catania front became stalemated, so Monty tried to extend it by bringing 51st (Highland) Division from XXX Corps up on the left of XIII Corps, but he was too late to affect a decisive blow against the enemy defences. Alexander’s decision to push both corps eastwards, taken on 16 July, was also too late to bring about the desired result. By this time the Axis defences had become sufficiently well knitted together to prevent the success of the strategy.

On 18 July Montgomery decided that 50th Division would hold fast in the Primosole area, while 5th Division would strike about three and a half miles west of the bridge, towards Misterbianco. The line of attack was to cross the Gornalunga and Simeto Rivers; any further west and it would have had to cross the Dittaino River as well. On the night of 18-19 July 13 Brigade succeeded in making a shallow bridgehead across the Simeto, through which 15 Brigade mounted an attack at 0130 hours on the 20th. The attack faded out, partly because the infantry battalions’ positions were unclear to the supporting artillery – all eight field and one medium regiments of it – and they were unable to bring effective fire down to assist the advance. In fact the infantry had advanced about three thousand yards before being brought to a halt by machine guns and mortar fire from the enemy who were situated in the gullies and ditches which criss-crossed the ground north of the river. A later attempt to restart the assault came to nothing when enemy defensive fire caused confusion and delay, and the division was ordered to consolidate where it was, pending changes in plans.

Further west again, by another eleven miles, Montgomery had hoped that 51st (Highland) Division would be in Paterno by the night of 20 July. General Wimberley intended to reach that town at speed, using his ‘Arrow Force’ on the right and 154 Infantry Brigade on the left. Arrow Force was an all-arms battle group based on Headquarters 23 Armoured Brigade, with 50th RTR (less two troops), 11th (Honourable Artillery Company) Regiment RHA, 243rd Antitank Battery RA, a company from 1/7th Middlesex Regiment – the Division’s medium machinegun battalion – and 2nd Battalion The Seaforth Highlanders. As such, it was a self-sufficient formation capable of acting relatively independently.

Paterno, however, was difficult to approach tactically, being on the far side of three rivers, the Simeto, the Dittaino and the Gornalunga. To get there, either the enemy defences at Sferro or Gerbini had to be penetrated; the two towns protected alternative routes. Arrow Force succeeded in making a shallow bridgehead over the Dittaino at Stimpano, on the Gerbini route, by 18 July, while 154 Brigade advanced through Ramacca with 152 Brigade behind it as the reserve which would exploit whichever route proved most promising. 153 Brigade was to the right moving on Sferro. Now Wimberley changed the direction of his advance, sending 154 Brigade through the Stimpano bridgehead towards Motta Station and 153 to Sferro with the intention of forcing a bridgehead across the Dittaino.

Both brigades ran into more opposition than expected. 154 Brigade was unable to cross the Simeto by dawn on 19 July. At Sferro, 153 Brigade’s 5th Battalion of The Black Watch made a bridgehead and dug in with mortars and antitank guns. The battalion was supported by machineguns from the Middlesex, and the guns of 127th Field Regiment RA. The defenders of Sferro brought down heavy fire on them from artillery, tanks and mortars, causing some sixty casualties, including the regimental sergeant major, who was killed when the battalion headquarters was hit. With enemy panzers in evidence ahead, and with only a single field artillery regiment in support, a rethink was necessary. Wimberley elected to try to enlarge the Sferro bridgehead that night, and 1st Gordon Highlanders and two companies of 5/7th Gordons moved forward through the fiercest bombardment they had ever endured to do just that. They crossed the railway line and then the main road, and 1st Gordons established their headquarters in the station yard, packed with goods wagons. The 5/7th Gordons’ companies forced their way into the village, but lost wireless contact when their radio sets were knocked out in the street fighting. They stayed, isolated, and were shot up by German 88mm guns and armoured cars when dawn broke. The Gordons were to remain in the bridgehead, unable to expand it in the face of stubborn enemy opposition, until 24 July.

Wimberley began to feel that his division was over-extended. On his right, the enemy defences appeared to be the strongest, and not the place to attack. However, he did not wish to redeploy his troops away from there, for to surrender the ground which they had already seized would mean that XIII Corps would have to retake it, should they find it necessary to move through the area. A renewed attack at Sferro was an option, but it was becoming clear that the enemy defences were firmly anchored on the area of Gerbini airfield, two thousand yards north of the positions now occupied by 154 Brigade. Wimberley decided that Gerbini should be taken during the night of 20/21 July by the brigade, supported by a squadron of tanks from 46 RTR and three artillery regiments.

1st Battalion Black Watch, followed by the 7th Battalion and the 7th Battalion Argyll & Sutherland Highlanders led the attack. 1st Black Watch became pinned down in front of the heavily defended barracks. 7th Black Watch, supported by the tanks, attacked the airfield, again against stiff opposition. The Argylls attacked Gerbini along the railway line, with artillery assistance, and after three hours of hard fighting gained their objective. The Argyll carriers and mortars, covered by a squadron of Shermans, moved up to join them, but the enemy – probably the Reconnaissance Unit and most of the 2nd Battalion Panzer Regiment, and two battalions from 2nd Panzer Grenadier Regiment, all of the Hermann Göring Division quickly responded with heavy fire and infiltration. The Argylls’ A Company was surrounded by enemy with tanks and was forced to surrender.

Before dawn most of the 1st Battalion of The Black Watch were also committed, and finally reached the barracks, which had by now been abandoned by the Germans. By 1030 hours a German counter-attack regained the ground they had lost. The action cost the Argylls eighteen officers, including the CO, and 160 men. 46 RTR lost eight Shermans, and the squadron commander dead.

Eight miles to the northwest of Sferro, XXX Corps planned the capture of a bridge over the Dittaino at Catenanuova that same night. The unit which was to carry out this task was 7th Battalion Royal Marines, a force which had provided the now redundant Beach Bricks, the troops that had administered (with medical, signals, ordnance, service corps, anti-aircraft units and the Royal Naval Commandos) each of the British landing beaches on D Day, but which was now reunited. With inadequate transport resources, much of the battalion had to hitch-hike its way sixty miles inland to join XXX Corps. The battalion was extremely tired – its work on the beaches had been very strenuous, and many men had been working in salt water for long periods during that stage of the landings. Their feet had become softened, and the long march to their present location had added to the difficulties. Furthermore, because of the limitations on transport, much equipment had yet to be brought forward. This included digging tools.

As the two wings of XXX Corps were on divergent courses, a dangerous gap was emerging at Catenanuova through which enemy armour might infiltrate. Two companies from 7 RM provided cover for the Corps Headquarters from this threat, and on 19 July fresh orders were given to the Marines which placed them under command of 51st Division, with the primary task of establishing a roadblock at Lennaretto, which would cover the division’s left flank. A further task, to establish a bridgehead over the Dittaino and the railway line beyond it, was also ordered. Once this had been achieved, the battalion was to advance of Catenanuova. The codename LEOPARD was given to this crossing, with 153 Brigade’s bridgehead at Sferro being named JAGUAR. A third bridgehead to the east, through which 152 Brigade was advancing, was christened LION.

The Royal Marines were supported in the attack to gain their bridgehead by a troop of Shermans, two batteries of 6-pounder antitank guns, a medium machine gun platoon of the Middlesex, and a battery of 3.7 inch howitzers. At 1400 hours, 19 July, two of the marine companies reached the battalion rendezvous south of two mountains which lay about 3,000 yards south of the intended river crossing site. They prepared a hot meal for the remainder of the battalion, which arrived two hours later. With reassurance from the Carrier Platoon of 4/5th Gordon Highlanders that the track ahead was suitable for mechanical transport, the plan was firmed up for one Marine company with an antitank gun to establish the roadblock at Lennaretto, while the remainder of the battalion made a night march and assault to secure the bridgehead over the Dittaino. The Gordons’ brief reconnaissance had indicated that no enemy were present south of the river, but that some movement had been seen on the north bank.

At dusk, 2000 hours, two companies moved forward and occupied the pass between the two mountains immediately north of the rendezvous point; a third passed through them and crossed the river without incident until Italian troops in a building near the railway raised the alarm. The position was taken at the point of the bayonet and several prisoners were taken. To the right, the first of the companies that had secured the pass moved up and crossed, again taking prisoners, and the third company advanced into the centre. By 0500 hours the far bank was secure, and some 100 Italian and fifty German prisoners were in the bag.

The infantry may have been on the north bank, but behind them the supporting antitank guns were having difficulties in coming forward to the position. The track between the two mountains was poor. It had never been used for motorised transport and the edge was crumbling, and a Bren carrier and two portees carrying 6-pounder guns went over the edge into a deep ravine; there was no possibility of tanks or artillery using the track. The Marines were without support apart from those few antitank guns which had made it to a ridge south of the Dittaino.

To compound their problems, the ground which the Royal Marines occupied was hard and rocky, and impervious to digging. Moreover, it was overlooked by two features to the north, Razor Ridge and the Fico d’India. Enemy on the second of these could enfilade British troops huddled in the only cover available, the railway embankment and the banks of the river. Soon the Marines came under very heavy fire from an assortment of weapons, directed from observation posts beyond the range of anything the British had. Self-propelled guns, Nebelwerfers (multi-barrelled mortars) heavy machine guns and 88mm guns firing airbursts, together with snipers, all pitched in. One 88mm gun was destroyed by the antitank guns south of the river before they in turn were put out of action by the Nebelwerfers. Four carriers attempted to bring the battalion’s 3-inch mortars across the river, but one bellied down on the approach, and although the other three came into action they were soon knocked out.