The battle of Caravaggio and the other battles were the set pieces of Italian warfare. Such battles were relatively rare, although it was naturally on these that the chroniclers concentrated. The administrative documents of military life rarely mention the battles except as an aside to explain casualties and losses of equipment. In this they are more realistic and more informative than the chronicles, but neither succeed in telling us what military life was really like. Fifteenth-century military diaries have yet to be discovered, but still an attempt must be made to get below the surface and look at the realities of military practice, the day-to-day activities of Italian soldiers.

One man who was a conscientious writer of diaries, at least during his official missions, was the Florentine Luca di Maso degli Albizzi. He was the brother of Rinaldo degli Albizzi, the leading Florentine statesman who was overthrown and exiled by the Medici in 1434. Luca, like many Florentines of his class, spent much of his life on missions as representative of the Florentine Republic, and in May 1432 he was dispatched as special envoy to the camp of the Florentine captain general, Niccolò da Tolentino, near Arezzo. For about three weeks he was with the army and his account of those days is an interesting insight which is worth looking at in some detail.

Luca degli Albizzi left Florence on 18 May with a junior assistant, Bernardetto de’ Medici, and fifteen followers. He spent the first night at Castel S. Giovanni in the upper Arno valley where he was met by the civilian commissary with the army and a group of condottieri who were also on their way to join the captain general. The 200 men of these condottieri were billeted some miles further on in Montevarchi, and it was agreed that Luca would pick them up there the next morning and they would all go on together to the camp. Luca was an early riser and the next morning he arrived at Montevarchi to find the soldiers still in bed. They were clearly billeted in houses all over the town, and it took until mid-day to get the squadrons assembled and on the road. They arrived at the camp in mid-afternoon to find that Niccolò da Tolentino had gone out the previous evening with a force of 700 men to try and catch the Sienese under Francesco Piccinino in a night ambush. As he was not yet back, Luca waited for a couple of hours and then rode to Arezzo to spend the night in comfort. Niccolò had in fact failed to catch the Sienese who had received warning of his intentions, but he had ridden all the way to Montepulciano which was being besieged by the Sienese and had sent supplies and more troops into the town before returning. This itself meant that Niccolò da Tolentino had ridden over 50 miles in the 24 hours, but this was not considered in any way extraordinary.

On the 20th Luca returned to the camp and spent six hours with the captain general and his senior officers. They drew up written plans for the campaign, and Niccolò outlined his immediate needs. The troops needed pay, but even more important he wanted 60 mules to carry provisions behind the army as he planned to move fast and did not want to waste time collecting food. He also wanted two or three bombards and some stonemasons to make balls for them. He thought that a few hundred militia auxiliaries would be useful, including 50 pioneers with spades and axes. Luca got off a messenger immediately to Florence with these requirements, and he himself began to ride round collecting the militia.

The strategic position which Luca and Niccolò da Tolentino faced was that a number of contingents of allied Sienese and Milanese troops were operating in southern Tuscany occupying castles and towns and damaging crops. Another Florentine army was camped near Pisa under Micheletto Attendolo, but the needs of the campaign were speed rather than great strength, so it was decided not to try and link up with Attendolo. Niccolò da Tolentino was very anxious to get on with it and declined an offer from Luca that he should postpone operations until the normal ceremony for handing him the baton as captain general had been arranged. News had come that the Sienese were besieging Linari and Gambassi in the Valdelsa, and speed was vital if these towns were to be saved. However, it was bound to take three or four days to collect what was needed and break camp.

After three days of intense activity, the militia, provisions, and munitions had been assembled, and at dawn on 24 May Niccolò da Tolentino moved off with his army of about 4,000 men. He had about 50 miles of difficult country to cover to reach the besieged towns, and as half of the force was made up of infantry and militia it could not move very fast. A messenger met them on the first day with the news that Linari had surrendered, but that the enemy forces were still divided into two camps, one commanded by Francesco Piccinino and the other by Bernardino della Carda. On the evening of the 26th the army reached Poggibonsi and there heard that the Sienese had united, taken Gambassi, and were now moving to meet Niccolò’s army. The night was one full of alarms and false alarms, in one of which Niccolò’s eldest son, Baldovino, was shot in the leg by a jumpy Florentine archer. Luca marvelled at the Captain’s self control when he heard of this incident.

The next day, Tuesday, Niccolò da Tolentino detached some of his infantry and militia north-westwards to begin the siege of Linari, and he himself went southwest to try and cut off an enemy march towards Siena. But again either he had received false information or the Sienese got word of his movements, and they doubled back and headed towards the Arno valley taking Pontedera on the way. This left Niccolò with the task of retaking Linari before he could move on in pursuit. He tried negotiations with the defenders, threatening to hang them all if he had to take the town by storm, but this proved useless. There were only 100 Milanese and Sienese infantry defending it, but it had good walls and they believed that Niccolò would not waste time over them. Indeed he did not plan to waste time; he wanted to get on and bring the enemy to battle, but he was determined to deal with Linari first. He only had small bombards and the weather was blazing hot, but nevertheless he ordered an assault at dawn on the morning of the 30th. Four breaches were made in the walls and Niccolò’s dismounted men-at-arms surged into the assault. After three hours of bitter fighting the town was taken and sacked. There were a number of casualties; all the professional infantry in the defence were held as prisoners, but the local defenders were allowed to go free; a number of women were also taken by the Florentines. Finally the walls of Linari were pulled down and half the town burnt. Linari was a Florentine town; the treatment of it was harsh but effective; this was partly a reflection of basic Florentine attitudes towards the subject towns, partly a matter of military necessity. The place had to be made useless to the Sienese otherwise this sort of warfare could go on indefinitely.

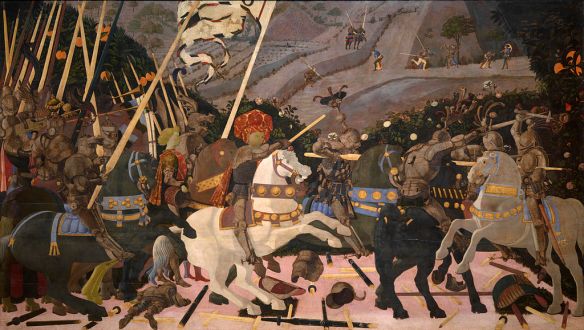

The next day Niccolò da Tolentino turned northwards to join up with Micheletto Attendolo and seek out the enemy in the Arno valley. By now the militia had melted away; they were getting far from their homes near Arezzo and the few days’ campaigning had been tough. On 1 June the army came out into the Arno plain. It was a Sunday and normally in Italian warfare this was regarded as a day of rest when little activity was expected. It was perhaps for this reason that Niccolò da Tolentino succeeded at last in catching the enemy. The Sienese had begun to besiege Montopoli, and Niccolò, moving rapidly now that his troops were out in the open country, came up on them fast. He and Luca went ahead with 30 cavalry and Luca who knew the area well pointed out the lie of the land. Niccolò felt however that he still did not have a clear enough idea of the enemy’s dispositions and so, while Luca stayed with the main body and gave an oration to the troops, he went on further ahead with a few men and thoroughly explored the enemy position. Then without further delay he launched his attack. The battle was short but hard fought, and Luca commented on the useful role of the infantry. The arrival of Micheletto Attendolo from the other direction completed what appears to have been a thoroughly well-planned and organised operation. The Sienese were completely routed, a number of captains and 150 men captured and 600 horses taken. Some of the prisoners escaped the next day as they were being escorted to Empoli, but were quickly rounded up. This battle, described by Luca degli Albizzi, was in fact the Rout of S. Romano later made famous by the series of paintings executed by Paolo Uccello for the Medici palace. Luca’s eye-witness account is somewhat different to traditional descriptions of the battle, which suggest that Niccolò da Tolentino was surprised with a handful of men and held out against enormous odds for eight hours until Attendolo arrived. No doubt a desire to glorify Niccolò’s achievement played some part in the distortions which have crept into the story, but Luca’s account of Niccolò leading a carefully planned attack does the condottiere no less credit in a different way.

The Florentine army got its rest day on Monday and then began to besiege Pontedera. This was, however, a more formidable task than the siege of Linari and without good artillery was likely to take some time. After a fortnight’s intense activity, during which the army had covered many miles of difficult country, taken a town by assault, and won an important victory, there was inevitably a lull. Luca degli Albizzi returned to Florence on the 6th to urge on the provision of supplies and artillery. He confessed that he felt completely exhausted.

This is an instructive glimpse into the life of an army and one which is all too rare in the fifteenth century. The mobility of Niccolò da Tolentino’s force, although half its strength consisted of infantry, is indicative of one of the major features of the warfare of the period. Luca degli Albizzi remarked at one point that only 300 of the 2,000 infantry in the army were concentrated together in one column and the rest were divided up amongst the cavalry squadrons. Does this perhaps mean that many of these infantry rode behind the men-at-arms on their horses when on the march? This could well be the explanation of the speed with which small armies could move. Niccolò da Tolentino’s army of course had very limited artillery and apparently no carts in the baggage train, but it did have 60 mules with provisions and was not living off the country. A larger army, and particularly later in the century, would inevitably have been much more encumbered with munitions and baggage. But it was usually the case that the heavy baggage was detached from the fighting elements of an army and moved on different routes in the rear.

We can get an impression of the activities of the other Florentine army in 1432 under Micheletto Attendolo from the letters written by Micheletto and his attendant commissaries to Florence. It had moved out of its winter quarters outside Pisa in late March and did not return to these quarters finally until mid-December. During the nine months, the army marched all over the Arno valley and deep into the hills on either side; it conducted at least four sieges and numerous skirmishes, but fought no major battle other than its tardy intervention at S. Romano. In 1440 Baldaccio d’Anghiari marched with a small force from Lucca to Piombino in two days—a distance of over 100 miles.

However, some of the most striking evidence for the mobility of mid-fifteenth-century armies comes from the campaigns of 1438–9 in Lombardy. The march of Gattamelata around Lake Garda in the autumn of 1438, when he escaped with his Venetian army from Brescia, became almost legendary in the annals of Italian warfare. Brescia was being closely besieged by the Milanese under Niccolò Piccinino and the direct route eastwards was well blocked. But it was essential to extricate Gattamelata’s main army, both because its size was creating serious provisioning problems in the beleaguered city and because without it the defence of the rest of the Venetian state, and particularly Verona, was dangerously weak. The only feasible escape route was over the mountains around the north of Lake Garda. It was a route which had never been used by large bodies of troops and was therefore thinly guarded by the Milanese. It was over this route that Gattamelata marched his army of 3,000 cavalry and 2,000 infantry, brushing aside the Milanese opposition and reaching Verona in five days. Piccinino was astonished by the feat, but he himself in the next year almost equalled it. Brescia was still being besieged and Gattamelata and Francesco Sforza marched to relieve it by the same route through the mountains. Piccinino moved north from Brescia to meet them and was badly beaten at Tenno. It was said that he escaped from the town, as the Venetian troops swarmed into it, carried in a sack on the back of a German soldier. However, he quickly rallied his forces and marched them around the south shore of the lake to attack Verona, while the Venetian army was still in the mountains. His forced march took Verona completely by surprise, and he occupied the city, although failing to take its two fortresses. Anxious messengers rode through the night to carry the news to Gattamelata and Sforza, and they, again acting with remarkable speed, marched back over the by then familiar road. It was once again the turn of Piccinino to be surprised; thinking that the Venetian army was still on the other side of the lake, his troops were contentedly looting Verona when Sforza and Gattamelata arrived outside the walls. Once more they had done the long march through the mountains in unbelievable time and the Milanese were in no position to defend their new possession. Piccinino and his men were bundled unceremoniously out of Verona having been its masters for less than three days.