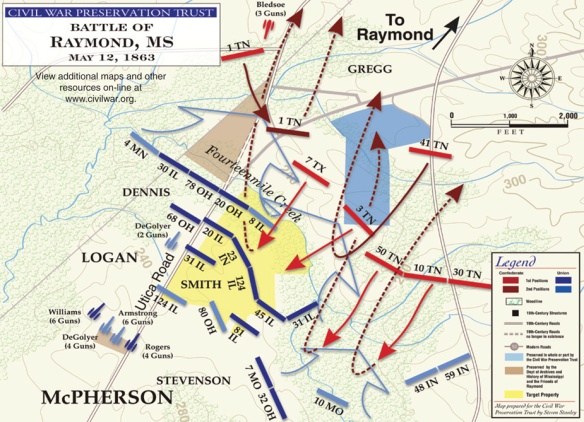

The Yanks want to pursue Walker’s retreating Tennesseans, but Colonel Farquharson’s 41st Tennessee arrives in the nick of time. The 41st turns to the west at the southern base of the ridge where Colonel Walker is trying to rally and opens fire on the Federal right flank as the men begin their pursuit coming out of the woods on the north side of the creek.

Hiram Granbury of the Seventh Texas still has his men banging away at the 20th Ohio in the creek bed, but he now has his left flank uncovered by the retreat of the Third Tennessee. And, on his right flank, his companies facing the Federal cannon have pulled back and gamely begin a march to the ridgeline to fill in where the Third Tennessee retreated.

But, with both flanks now uncovered, Granbury falls back, and he rallies at Bledsoe’s guns with Colms’s First Tennessee Battalion as support. As Granbury’s Texans approach Bledsoe’s position, the rifled Whitworth bursts, which leaves the Confederates with only two 12-pounder smoothbores. Bad luck for the Rebels!

All this time, Marcellus Crocker’s division has been strung back down the Utica Road due to all the dust, and Col. John B. Sanborn’s brigade doesn’t arrive on the field until 1:30. McPherson orders it into position to the left of Dennis’s brigade, which places it on the left of the already crowded Union line. Crocker’s artillery is still down the road, so the six guns of the Third Ohio Light Artillery, which belong to Logan, are sent to the far left to support Colonel Sanborn’s brigade. These cannon go into battery about 350 yards west of the Illinois 24-pounders. This Ohio battery has four rifled bronze Model 1841 6-pounders, like the ones in De Golyer’s battery, which they like to call 12-pounder James rifles, and two Model 1841 6-pounder smoothbores.

As the Third Ohio goes into battery, Sanborn cautiously advances his brigade and makes contact at the creek with the left flank of the 30th Illinois. With Sanborn’s brigade on the battlefield, 7,000 soldiers in blue are fighting the 3,000 in gray, along with 16 Union guns against two Confederate, now that the Whitworth has burst.

Since the Texas companies on the Confederate right flank have withdrawn and moved east toward the ridge to support the Third Tennessee, McPherson thinks he can spare units from his left. He orders Sanborn to send the two regiments on his left flank, the 48th Indiana and the 59th Indiana, over to the center of the Union line. These men slowly back out of the woods along the creek, and quickstep eastward through the dust and smoke behind the lines to the center of the Union line, and there they report to Colonel Dollins of the 81st Illinois.

Dollins has his famous temper up, and he tells them, “I don’t need your damn help—my men have the situation well in hand.” So the two Hoosier regiments form up in the field, file to the right, and wait like reserves for something to happen. Had they stayed on the Union left, they could have been used in a flanking maneuver.

Farther out on the Union right, the two right flank regiments, the Seventh Missouri and the 32nd Ohio, have slipped eastward through the woods bordering Fourteenmile Creek and have skirmished with Beaumont’s 50th Tennessee, causing Beaumont to withdraw to the Gallatin Road. The Ohioans pull to within a hundred yards of the road, fire a few parting shots at Beaumont, and take a break in a wooded ravine. But the Seventh Missouri, a regiment from St. Louis composed largely of recently arrived Irish immigrants with a sprinkling of hard rock miners, slides to the left to reestablish contact with the right of the 31st Illinois. Now that they have secured their left flank, the Irishmen, sweating profusely, swearing in Gaelic, and looking for a fight, debouch from the woods and start up the hillside to their front.

The Union Irishmen soon find a fight, because red-bearded and handsome Randy MacGavock, whose 10th and 30th Tennessee Infantry is supposed to follow Beaumont in the en echelon attack, finally realizes that Beaumont is not going to attack. Then MacGavock receives orders from Gregg to march to the right and stop the hemorrhaging in the Confederate line where the Third Tennessee has been pushed back across the creek and up the hillside. MacGavock, a Harvard law school graduate and a former mayor of Nashville, is ready to go, and he marches his Irish bullyboys back to the ridge north of Fourteenmile Creek. He then forms his lines on the left of Farquharson’s 41st Tennessee, which has recently moved into position.

MacGavock can see the Irishmen of the Seventh Missouri coming up the hill. He knows he’s got to do something. Despite the heat, he wears a long gray cloak with a bright red lining, and he throws it back over his shoulder. This might inspire his men, but it turns out to be a bad move, because some of the battle smoke has cleared, and the Yankee redlegs look over their cannon barrels to the hillside to their right front, and see MacGavock’s men forming on the ridgetop. They see a bright red flash of color in the gray line, and they shift their fire to that spot. As the shells come in, MacGavock knows he is in a tough situation. If he falls back, the Confederate line will collapse, and if he stays where he is, the artillery will hammer his men to pieces. So the only thing left to do is to pitch into those blue uniforms of the Yankee Irish coming up the hill.

The blue Missourians, in one of those strange coincidences of war, are carrying a green flag with a golden harp, much like the one in MacGavock’s Rebel Irish regiment. But the Missourians have Gaelic on the red banner of their flag, which says, “Erin Go Bragh,” or Ireland Forever. The Tennesseans have English on the red banner of their flag, saying, “Go Where Glory Waits You!”

As MacGavock charges downhill at the front of his men, with Federal shells whizzing overhead, he is cut down by a Federal sharpshooter. Even with their commander shot and dying, the Confederate Irish charge downhill and smash into the Union Irish. The Yanks fight hard but soon break, and they fall back into the woods, where they are covered by the flanking fire of the 31st Illinois to the west of them. There are far too many Yanks in the woods for the Tennessee Irishmen to handle, and they slowly fall back to the crest of the ridge and hunker down. The Missouri Irish soon regroup and press back uphill, but the Tennesseans won’t budge. Volley after volley is exchanged at short range on top of the ridge between the opposing Irish regiments. Then the men of the 10th and 30th look to their right and see Farquharson’s men suddenly about-face, and file off to the east toward the Gallatin Road. Before the Yanks can exploit the gap in the Confederate line, it is filled with the three beaten-up companies of Texans, who still have plenty of fight left in them, and have marched over from the Confederate right flank near the Fourteenmile Creek bridge.

While this is happening, Col. Samuel Holmes’s brigade of Crocker’s Union division arrives on the low rise where the 16 Federal guns are blasting away. Now, the Union troop numbers rise to 9,000, and their artillery goes up to 22 cannon, because the six guns of the 11th Ohio Light Artillery of Crocker’s division arrive and go into battery in the gap between De Golyer’s cannon and the Illinois 24-pounders. The 11th Ohio has two 12-pounder howitzers, two 12-pounder James rifles, and two 6-pounder smoothbores.

When Holmes comes up, he is told to send the Tenth Missouri and the 80th Ohio to assist the Seventh Missouri, whose men cannot penetrate the Confederate line. The Missourians of the Tenth are placed on the right of Stevenson’s brigade, and Stevenson posts the Buckeyes in reserve.

But where were Farquharson’s Tennesseans going when they left the right flank of the 10th and 30th Tennessee? Gregg, not knowing that Colonel Beaumont was still out on the Gallatin Road, has ordered Farquharson out to the road, thinking a threat was developing there. It wasn’t. At the same time, Beaumont, on the Gallatin Road, decides to march to the west to the sound of the firing, since there is no threat where he is. The two Tennessee regiments change places on the battlefield, and as they pass each other, nobody in either unit bothers to stop and ask where the other is going. Beaumont’s 50th Tennessee ends up on the right flank of the 10/30th Tennessee, and Farquharson’s 41st Tennessee ends up on the Gallatin Road.

By 4 p.m. Gregg realizes that he has bitten off a lot more than he can chew, and he seeks to get rid of that mouthful. But he has to worry about how he is going to save his command from overwhelming numbers. He sends Colms’s First Tennessee Battalion down the west side of the Utica Road from its position at Bledsoe’s guns, and these Tennesseans feign an attack on the Union left. The bluff works, and the Fourth Minnesota of Sanborn’s brigade hunkers down in the woods at Fourteenmile Creek and doesn’t advance.

Feeling good about his work, Colms shifts his men to the east side of the Utica Road so that they can cover the withdrawal of the beat-up Texans. As the Confederates start to withdraw, Beaumont, who has just marched his 50th Tennessee from the Gallatin Road and has arrived in the front of the masses of Union troops, realizes that he is in a tough spot, so he marches up a ravine in the ridgeline and then west to the Utica Road. Here he is joined by six companies of the Third Kentucky Mounted Infantry that have ridden out of Jackson to assist Gregg, and the horse soldiers cover the retreat.

Fortunately, Farquharson’s Tennesseans, now way out by themselves on the Confederate left on the Gallatin Road, realize the situation is hopeless, and they fall back and go north up the Gallatin Road, through the cemetery, and into Raymond before they are cut off.

There is no pursuit by the Federals, not even by the cavalry, so Gregg’s command rallies in Raymond and marches eastward toward Mississippi Springs on the Jackson Road.

When Gregg’s men depart Raymond that morning the ladies of the town set up a huge picnic spread beneth the stately trees along the road for the brave, and presumably victorious, Confederates when they come back into town. But the Confederates have to conduct a fighting withdrawal to escape all those Yankees, and when they pass through Raymond, they don’t have time to stop and feast. So the guys that are going to get the food prepared by the ladies of Raymond are the 20th Ohio, because they are the first ones into Raymond as the Confederates head out the Jackson Road.

The Battle of Raymond is over. It has lasted six hours. The Southerners, though decisively outnumbered, held the initiative for almost five hours. But they lose more men because many are taken prisoner. No Federals are captured. The Confederate losses are 73 dead, 252 wounded, and 190 missing, for a total of 515 casualties. Of course, many of the wounded will later die. The Federals have 66 killed, 339 wounded, and 37 missing, for a total of 442.

The Battle of Raymond shocks McPherson, but he proves himself to be a spinmaster. He sends a report to Grant, who is only six miles to the west, that he has fought a “sharp and severe contest” against 6,000 Confederates and two batteries. He doubles their size to a number which has to concern Grant, who heard the battle from six miles to the west, and his experienced ears tell him there were no 6,000 Rebs, much less 12 Confederate cannon, at Raymond.