The pass seemed to be empty of enemy forces. The day before, an armored convoy coming from Egypt had crossed the canal and penetrated the pass, but Israeli jets had attacked and destroyed it completely. The black carcasses of the burned vehicles still smoked all along the Mitla road.

Sharon sent a radio message, asking permission to take the Mitla Pass. But the General Staff radioed him a clear order: “Don’t advance, stay where you are.” Sharon, Raful and the other commanders didn’t know that the goal of the paratroopers’ drop at the Mitla approaches was not fighting or conquering, but to serve as a pretext for the Anglo-French intervention.

In the early morning another message arrived from the staff: “Do not advance!” But Arik did not give up. At 11:00 A.M. Colonel Rehavam (“Gandhi”) Ze’evi, the Southern Command chief of staff, arrived at the compound in a light Piper Cub plane. Arik again requested permission to enter Mitla, but Gandhi allowed him only to send a patrol to the pass, on the condition that he wouldn’t get entangled in fighting.

Arik immediately assembled a “patrol team” under the command of Motta Gur. At the head of the column Arik placed six half-tracks; behind them the half-track of the tanks force commander Zvi Dahab and Danny Matt; then three tanks; then the brigade deputy commander, Haka Hofi’s, half-track; six more half-tracks full of paratroopers; a battery of heavy 120-millimeter mortars; and several equipment-carrying trucks. The paratrooper commando joined the column not as fighters but as tourists who came to enjoy the trip to the canal. Davidi made a funny hat out of a newspaper, to protect himself from the sun.

And Arik called all this battalion-sized convoy a “patrol.”

At 12:30 P.M. the convoy entered the pass. They quickly advanced in the narrow canyon, between two towering mounts.

And there the Egyptians were waiting.

Hundreds of Egyptian soldiers were entrenched in dugouts, natural caves in the rock and behind low stone fences. On the roadside, camouflaged by bushes and bales of thorns, stood armored cars carrying Bren machine guns. Companies of soldiers were positioned above them, armed with bazookas, recoilless guns, anti-tank guns and midsized machine guns. And on a third line above, in positions and cubbyholes in the rock, lay soldiers armed with rifles and automatic weapons.

At twelve-fifty, the half-tracks advancing in the pass were hit by a lethal volley of bullets and shells. A hail of bullets drummed on the half-tracks’ armored plates. The first half-track swayed to and fro and stopped, its commander and driver dead; the other soldiers, some of them wounded, jumped off the vehicle and tried to find cover.

Motta Gur’s half-track was about 150 yards behind. He ordered his men to advance toward the damaged vehicle. Three half-tracks reached the immobile vehicle and were hit too. Motta got around them and tried to escape the ambush, but he was hit as well. He and his men sought refuge in a shallow ditch beside the road.

Haka, who was in the middle of the column, realized that his men had blundered into a deadly ambush. He ordered Davidi to get back and stop the vehicles that had not entered the pass yet. Davidi unloaded the mortars and opened fire on the hills. Haka himself broke through the enemy lines with a company and two tanks. The armored vehicles bypassed the stuck half-tracks and emerged on the other side of the pass, two kilometers down the road.

Mitla, full of burned, smoldering vehicles from the Egyptian convoy from the day before, now became a killing field for the paratroopers. Four Egyptian Meteor jets dived toward the column, blew up eight trucks carrying fuel and ammunition, and hit several heavy mortars.

Motta sent an urgent message to Haka, asking him to come back into the pass and rescue the trapped soldiers. He also requested from Davidi that Micha Kapusta’s commando should attack the Egyptian positions from behind.

Micha’s commando—the finest paratrooper unit—climbed to the tops of the hills. His platoon commanders started moving down the northern slope, annihilating the Egyptian positions. But at this point a terrible misunderstanding occurred.

The commando fighters that destroyed the enemy positions on the northern slope clearly saw the road. They didn’t notice that the slope turned to a sheer drop almost at their feet, and most of the Egyptians were entrenched there. They also failed to notice other Egyptian positions that were located on the southern slope, across the road.

Suddenly, Micha’s men were hit by a hail of bullets and missiles from the southern slope. Micha thought that the trapped paratroopers by the road were firing at him. Furious, he yelled at Davidi on his radio to make Motta’s people stop firing, while Motta, who couldn’t see the enemy positions on the southern slope that were firing at the commando, did not understand why Micha didn’t continue his advance.

These were tragic moments. “Go! Attack!” Davidi yelled at Micha, while Micha saw his men falling. The paratroopers dashed forward under heavy fire. Some reached the edge of the rocky drop without noticing it and rolled down, in full sight of the Egyptians, who shot them.

Facing heavy fire, Micha decided to retreat to a nearby hill. But another Israeli company appeared on top of that hill and mistakenly started firing on Micha’s men. Micha’s fury and pain echoed in the walkie-talkies. His soldiers were fired at from all sides, by Egyptians and by Israelis.

At last Davidi understood the mix-up that had caused Motta’s and Micha’s contradictory reports. He made a fateful decision: send a jeep that would attract the enemy fire into the pass. Davidi’s observers would then locate the sources of the Egyptian fire.

For that mission he needed a volunteer who would be ready to sacrifice his life.

“Who volunteers to get to Motta?” he asked.

Several men jumped right away. Davidi chose Ken-Dror, his own driver.

Ken-Dror knew he was going to his death. He started the jeep and sped to the pass, immediately becoming the target of heavy fire. The jeep was crushed and Ken-Dror collapsed beside it. His sacrifice was in vain. Motta and Micha didn’t succeed in pinpointing the sources of enemy fire.

Davidi sent a half-track with four soldiers and a lieutenant to the pass. The carrier reached Motta, loaded some wounded soldiers and returned, unharmed.

And the sources of the shooting still were not discovered.

Davidi again ordered Micha to storm the Egyptian positions. His soldiers ran again down the slope. Another platoon was hit by crossfire from the southern hill. And Micha suddenly saw the abrupt drop at his feet and understood where the Egyptian positions were.

At that moment he was shot. A bullet pierced his chest, he lost his breath and he felt he was going to die.

“Dovik!” he shouted at his deputy. “Take over!”

A bullet hit Dovik in the head. The two wounded men started crawling up the hill. In front of them they saw other paratroopers. They feared their comrades would shoot them by mistake. “Davidi! Davidi” they shouted hoarsely.

At 5:00 P.M. a rumble of tanks suddenly echoed in the narrow canyon. Haka’s two tanks returned from the western exit of the pass and turned the tide. They first set their guns toward the southern hill and blasted many of the enemy positions. Egyptian soldiers started fleeing in a disorderly way but were mown down by the paratroopers’ machine guns. Simultaneously, two paratrooper companies reached the crests of the two ridges rising on both sides of the road. They came from the western entrance to the pass and systematically mopped up the Egyptian positions. They agreed that their finishing line would be a burning Egyptian half-track in the center of the canyon. Other fighters would come from the east and destroy the remaining enemy positions on the northern and southern hills.

At nightfall fifty paratroopers scaled the hills—half of them, commanded by a twice-decorated veteran, Oved Ladijanski, turned to the southern ridge; the other half, under the leadership of a slim and soft-spoken kibbutz member, Levi Hofesh, attacked the northern one. Their goal was to reach the burning half-track with no Egyptian soldier left behind.

Oved’s unit moved up the hill in silence, holding their fire. They reached a fortified machine gun position, hewn in the rocky slope. They attacked it from below with hand grenades, but some of those bounced off the rock and exploded. Oved threw a grenade toward the machine gun, but the grenade rolled down. “It’s coming back,” Oved whispered to the soldier beside him, pushed him aside and covered him with his body. The grenade exploded against Oved’s chest and killed him. One of his comrades succeeded in dropping a grenade into the position, burst in and killed the Egyptians cowering inside.

The survivors of Oved’s unit kept advancing and destroying the enemy positions. Levi Hofesh did the same on the northern hill. He realized that the Egyptians had placed their forces in three tiers, one above the other. He divided his soldiers in three detachments, and each mopped up one of the enemy lines. The fighting was desperate; the trapped Egyptians had nothing to lose. It took the paratroopers two hours to advance three hundred yards. Shortly before 8:00 P.M., Levi completed his operation, leaving behind ninety Egyptian dead.

The paratroopers now were the masters of the Mitla Pass. During the night, cargo planes landed nearby and evacuated the wounded—Dovik and Micha, Danny Matt and another 120 paratroopers. Among the seriously wounded was also Yehuda Ken Dror, hanging to life by a thread. In a few months he would succumb to his wounds.

Thirty-eight paratroopers and two hundred Egyptian soldiers died in the Mitla battle. Four more Israelis would die later of their wounds. Dayan seethed with fury, accusing Sharon of losing so many lives in a totally unnecessary battle. Ben-Gurion, alerted, refused to interfere in a row between two senior officers whom he especially liked. But the Mitla battle actually sent Sharon to an informal exile and delayed his advancement in the IDF by several years.

The Mitla battle was gratuitous, indeed. Yet it was a bravely fought battle, in which Sharon’s paratroopers demonstrated his principles that one doesn’t abandon comrades on the battlefield, even if it costs human lives, and an IDF team doesn’t bend, doesn’t give up and doesn’t retreat until the mission is achieved.

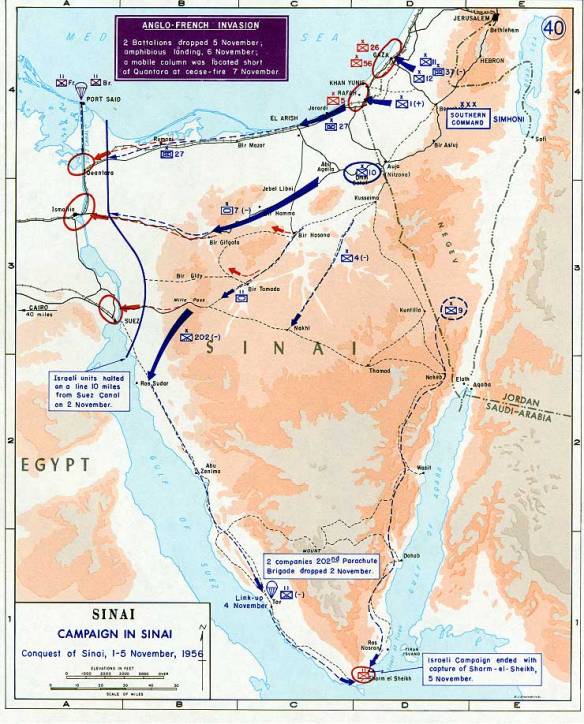

The Sinai campaign lasted seven days and ended with an Israeli victory. Israel had beaten the Egyptian Army and conquered all of the Sinai Peninsula. The Franco-British invasion, on the other hand, failed miserably. The Israeli triumph marked the beginning of eleven years of de facto peace on the southern border that would abruptly end with the Six Day War.

RAFAEL “RAFUL” EITAN, COMMANDER OF THE 890TH PARATROOP BATTALION AND LATER THE CHIEF OF STAFF

[From an excerpt from his book, A Soldier’s Story: The Life and Times of an Israeli War Hero, written with Dov Goldstein, Maariv, 1985]

“I was standing closest to the aircraft door. A bit of excitement always hits you over the parachuting site, even if you’ve done it many times before. All the more so at the start of a large-scale military campaign, at such a distance from Israel. You’re plunging into the unknown, into enemy territory. The cockpit of the next plane in the formation was directly across from me, mere feet away. I waved to the copilot. He held his head in both hands, as if to say, ‘What you’re about to do . . .’

“Red light. Green light. I’m in the air, floating down, over the Mitla crossroads. It’s five in the afternoon, dusk. The sun is setting. You can hear a few shots. My feet hit the ground. I release myself from my parachute, get organized quickly. We take our weapons out of their cases. We hold positions in the staging territory. The companies spread out. It’s already dark. We put barriers into place. We lay mines. We dig in, hole up. There are trenches there from the days of the Turks. This makes our work easier. Our two forces take positions at the Parker Memorial, to the west, and en route to Bir Hasna, to the north. We mark the ground intended for receiving the supplies being parachuted in.

“At night I went to sleep. . . . One must muster his forces before experiencing the pressure of combat. One must remove the stress and the emotions to a secluded corner. I dug myself a foxhole, padded it with the cardboard from the parachuted supplies, spread down one or two parachutes, and tucked myself in. Good night by the Mitla.”