The siege of Madras in 1746 for Joseph Francois Dupleix troops and ships of La Bourdonnais. The city surrendered in September 1746. Madras was returned to England in 1748 to restore peace.

That nameless Spanish coastguard who, in defence of his country’s trading rights in Cuba, sliced off the ear of Captain Robert Jenkins had much to answer for. In an age when even sea dogs wore ample wigs the Captain’s loss was of no cosmetic consequence; but the fact that Jenkins ever after cherished the severed organ, regarded it as a talisman, and chose to exhibit it in the House of Commons had far-reaching repercussions. Such was the clamour for retaliation against Spanish highhandedness in the Caribbean that the war, when at last declared by a reluctant ministry, is said to have been the most popular of the century. It was also one of the shortest, for within a few months the Hapsburg emperor had died, opening the issue of the imperial succession and plunging central Europe into conflagration. The War of Jenkins’s Ear became subsumed in that of the Austrian Succession and, with Britain already committed against Bourbon Spain, it was unthinkable that Bourbon France would be other than hostile.

The success of the European powers in engrossing the world’s trade had had the unfortunate side effect of multiplying and internationalizing their interminable squabbles. If an incident off the coast of Cuba could determine postures in a European war it followed that wherever else the European rivals found themselves in close proximity the same hostile postures would be likely to prevail. Nationalism, let alone religion or ideology, played no great part in these quarrels. Ostensibly they were dynastic or commercial but the issues, often confused in the first place, became hopelessly obscured in the process of export. Local grievances took their place and local conditions determined the scale and duration of any hostilities. The stakes could by mutual consent be kept to a minimum or they could escalate to such heights that in retrospect they dwarfed the often inconclusive results in Europe.

So it was in India. News that Britain and France were officially at war reached the Coromandel Coast in September 1744. By that time the question of the Austrian succession was as dead and buried as Jenkins and his ear. But that scarcely troubled the participants. Two years later Madras would be stormed and captured by the French; and for the next fifteen years the two nations, in the guise of their respective trading companies, would fight a life-and-death struggle for supremacy on The Coast and in the adjacent province of the Carnatic. To strengthen its position, each Company entered into alliances with the native powers, thereby extending both its influence and its territory. Honours would be more or less equally divided but in the end victory and dominion fell to the British; and thanks to the military arrangements necessitated by the war, the British would go on to realize an even greater dominion in Bengal. It is therefore with this war, the War of the (wholly irrelevant) Austrian Succession, that most histories of British India begin; there are even histories of the East India Company which have the same starting point.

The metamorphosis of the Company’s Madras establishment from city state to territorial capital, closely followed by the still more dramatic transformation of its Bengal establishment, undoubtedly represents the most important watershed in the Company’s history. Bengal at the time accounted for more than fifty per cent of the Company’s total trade and Madras for around fifteen per cent. When the call to arms drowned out the commodity wrangling in two such important markets, it was bound to affect the whole posture of the Company.

On the other hand, these stirring events had little bearing on the Arabian Sea trade, based on Bombay, and even less on the important China trade, based on Canton and now entering a period of rapid expansion. In outposts like Benkulen and St Helena the usual grim and inglorious struggle for survival continued regardless. And more significantly, even in Bengal and on The Coast the volume of trade remained high in spite of the political turmoil. The Coast’s trading returns would be back to normal within two years of the French occupation of Madras while those of Calcutta would recover from their own ‘black hole’ in 1756 even more rapidly. In chronicling the political and military adventures of the period it is rather easy to forget that the Company remained a commercial enterprise. ‘The combatants aimed at injuring one another’s trade, not making conquests’, writes Professor Dodwell, editor of the Cambridge History of India. Commercial priorities still governed the Company’s decision making and it was its financial viability which made expansion possible – though not necessarily desirable.

That said, any student of the Company’s fortunes who at last arrives at this watershed period will find little further use for a pocket calculator. With the Company in India fighting for its very existence, the monthly returns of ‘The Sea Customer’ and ‘The Export Warehousekeeper’ lose their charm while London’s always wordy complaints about the previous year’s taffetas seem as irrelevant as Mrs Gyfford’s last will and testament. More territory meant more revenue but not necessarily more trade; and for Company diehards that was one good reason for a certain ambivalence about the whole question of territorial expansion.

This shift away from the market place is amply endorsed by all that has been written about the period. Whereas for the first 150 years of the Company’s existence the published sources are few and specific, to be eagerly sought and gratefully scrutinized, now the student is suddenly confronted by such a mass of research, analysis, narrative, and polemic as to make his task seem superfluous if not impossible. Sandwiched between the ample volumes of political, military and administrative history stand the classic pontifications of Macaulay and Burke, important French and Indian chronicles, much London-based pamphleteering, and copious biographical writings from which the main protagonists emerge with rich and ready-made personalities. After so long diligently pursuing faceless factors engaged in obscure transactions up forgotten backwaters, it is all rather overwhelming – like emerging from a long night drive through country lanes on to a floodlit freeway. Only a nagging doubt that the freeway may not be heading in quite the desired direction dispels euphoria.

For the fact is that nearly all of this material celebrates the rise of British power in India, a process of consuming interest to several generations of English writers but one in which the Company’s prominence becomes increasingly deceptive. For this same process heralded and then hastened the eclipse of the Honourable Company as a private commercial enterprise. Its stock would be quoted for another 130 years but its trading rights would disappear in half that time; its governance would last for over a century but its independence would be gone in just four decades,

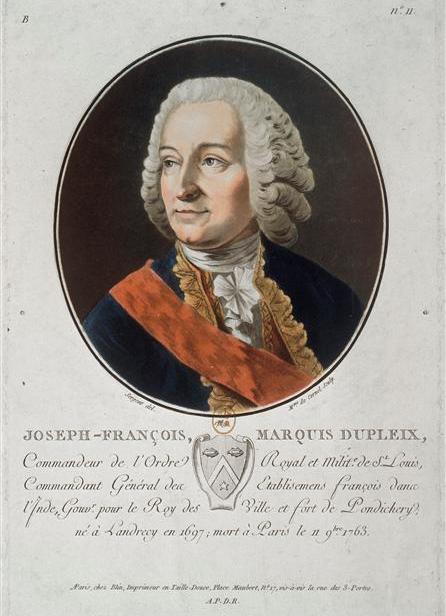

How ambivalent the Company was about military adventurism is well illustrated by its reponse to those first tidings of war with France in 1744. During the War of the Spanish Succession, the French and English companies in India had agreed to refrain from hostilities, and it was with the idea of a similar pact that Marquis Dupleix, now the Governor of Pondicherry, wrote to Nicholas Morse, his opposite number at Madras. Morse knew that Dupleix’s position was weak, that Pondicherry’s defences were little better than those of Madras and that there was no French fleet in the offing to boost them. He also knew that a squadron of the Royal Navy was already on its way to bolster his own position. Yet the idea of a pre-emptive strike against Pondicherry seems never to have entered his head. He could not accept Dupleix’s offer of a pact because, as he explained, he was not authorized to do so. He was thinking, of course, of the Royal squadron which was sure to take French prizes and over which he had no authority. But neither did he reject the pact. In Bengal the English at Calcutta and the French at their neighbouring base of Chandernagar would observe it; Morse merely prevaricated.

Irritated by this caution Dupleix appealed to the Nawab of the Carnatic who duly reminded both Companies that they held their settlements of the Moghul Emperor on condition that ‘they behave themselves peacable and quietly’. In effect the Nawab forbade hostilities and in the correspondence that followed Morse was obliged to define his position. What happened at sea, claimed the Madras President, was of no legitimate concern to the Nawab but on land he could vouch for the English never being the first to take up arms; their trade was too important, their militia too ineffectual.

By now it was 1745 and the Royal squadron under Commodore Curtis Barnett had arrived in Eastern waters. Instead of making straight for the Coromandel coast, Barnett first cruised off Aceh where he pounced on French shipping richly laden with China goods as it emerged from the Malacca Straits. Four or five vessels belonging to the Compagnie des Indes were taken along with a like number of privately owned ships in which the French factors, and especially Dupleix, had a very considerable interest. As with the English of the period so with the French; it is impossible to tell which affront was the more provocative, a tear in the flag or a hole in the pocket. But when, as now, both national honour and personal wealth were at stake, a vigorous response could be expected. Dupleix wrote urgently to Mauritius, the Compagnie’s main base in the Indian Ocean, for naval support; he again complained to the Nawab of the Carnatic; he protested loudly to Madras; and he began assembling a small expeditionary force in Pondicherry.

News of the last caused consternation in the English settlements. Morse convened his Council in emergency session. It was agreed to hire ‘200 good peons’, or militiamen, from Madras’s immediate neighbours and to arm all the city’s resident Englishmen with matchlocks; they could take the guns home with them but if they heard a cannon shot during the night they were to ‘repair to The Parade before the Main Guard where they would receive the necessary orders from Mr Monson, their Commanding Officer’. Such was Madras’s idea of mobilization; never were sabres rattled so diffidently. Fort St David, only ten miles from Pondicherry, was the more obvious target but Morse refrained from sending it reinforcements on the doubtful grounds that that might be just what Dupleix wanted; with Madras deprived of part of its garrison the French might take advantage of a southerly wind and ‘surprise us’.

In the event it was all a false alarm. With the English squadron daily expected, Dupleix knew better than to do anything that might invite an attack on Pondicherry; his expedition was intended simply to reinforce a recently acquired factory at Karikal some fifty miles down The Coast. When at last Barnett did arrive at Fort St David, the Madras Council discharged the ‘200 good peons’ and turned its attention to the more agreeable task of provisioning the squadron; meanwhile the squadron concentrated on the even more lucrative task of prize-taking. Trade was not neglected. ‘Having at present the prospect of making a very considerable investment this year’, the Council’s only anxiety was that the usual supply of shipping and treasure from home should reach them safely. This it did in December and not only were there four Company ships but also two further men-of-war and some more recruits for the garrison.

Two months later, in February 1746, news came from Anjengo, that source of so much shipping intelligence, that a French fleet of six warships was now ready to sail from Mauritius. Madras again cast about for mercenaries; in this case ‘300 Extraordinary Peons’ were signed up. But with Barnett still cruising off The Coast there was no panic. At the end of April Barnett died and was succeeded by Edward Peyton, his second in command. Still there was no sign of the French fleet. Peyton then cruised south towards Sri Lanka; there were ‘no ships in Pondicherry road’ according to a report that was before the Madras Council on 11 June.

The Council was now meeting twice a week, on Mondays and Wednesdays. On Monday the 16th there was further shipping news from Anjengo, this time about a homeward bound Indiaman; then there were some cash advances to Indian buyers to be approved, and an explanation to be sought from a ship’s captain lately arrived from Bengal and seven bags short on his manifest of saltpetre. Finally a letter was drafted to Fort St David approving of their design for ‘a new arched godown’ and promising to send some more field guns ‘as opportunity offers’. And so to dinner. No hint of panic, nothing frantic nor even faintly ominous. But at this point, a hundred years after Francis Day had first built his four-square fort on the Madras sands, the Fort St George records fall silent. It would be three years before the ‘Diary and Consultations’ book was resumed.

Doubtless there were other Council meetings during the few weeks that remained to the English in Madras but either they were too fraught to be minuted or, more likely, the records were destroyed by the French. From other sources, especially the deliberations of the junior Council at Fort St David, we know that within ten days Peyton’s squadron had fought an inconclusive action with the French fleet as it passed the Dutch settlement of Negapatnam. Peyton continued south to Sri Lanka for refitting and La Bourdonnais, the French commander, to Pondicherry. The latter’s fleet consisted of nine ships, according to the much alarmed factors at Fort St David; many of them were far bigger than the English ships; they off-loaded a vast quantity of treasure and, unreported by Fort St David, they carried some 1200 mainly European troops.

At the end of July the French fleet again put to sea. Again they encountered Peyton off Negapatnam, but this time the English turned tail before a shot was fired. Peyton then continued north, past Fort St David, past Madras, to Pulicat, a Dutch station. Unaware of this development, the English factors at Fort St David watched the French fleet return to Pondicherry.

By now, late August, it was common knowledge ‘that their design was against Madras’ and ‘that not only the Company’s expected Shipping but likewise their Settlement were in Eminent [sic] danger.’ It was Madras’s turn desperately to appeal to the Nawab and still more desperately to scan the horizon for a sign of Peyton’s fleet. From Fort St David letters were sent ‘by three several conveyances’ to Negapatnam (Dutch) and Tranquebar (Danish) to summon Peyton ‘wherever they heard he was [and] at any expense’. Native catamarans scoured the coastline even down to Sri Lanka; in response to a promised reward of 100 pagodas for the first sighting of the English fleet, some ventured out of sight of land and into over thirty fathoms. But it was all in vain. Peyton had decided that the fate of the Company’s settlements was no concern of his; where was the prize money in it? At the beginning of September he resumed his voyage north to Bengal, safety, and eventual obloquy. Madras stood alone and unprotected.