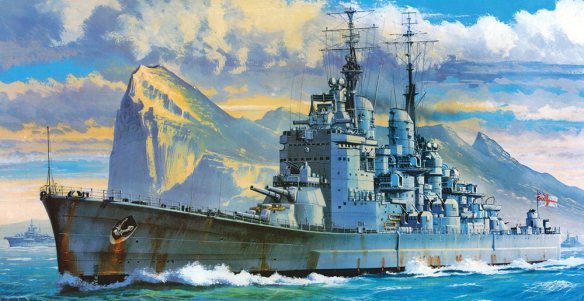

The last battleship of the Royal Navy, HMS Vanguard, with eight 15in guns in four turrets.

The Royal Navy in 1945 was a different service from the one that had gone to war in 1939. Manpower had actually peaked in mid-1944 and had already begun to fall but the number of ships was at its peak in 1945.

This was a modern navy and a well-balanced fleet, possibly more so than at any time in its history. The irony was that the two oldest aircraft carriers, Furious and Argus , had survived the war while all the other pre-war aircraft carriers had been lost. By this time, these two veterans were no better than hulks. In fact, those ships that had served through the war were almost all in dire need of a heavy refit as not only had they taken battle damage, but routine refits had been neglected because of the pressure on the Royal Navy to keep as many ships at sea as possible, while its three main bases were also subjected to heavy aerial attack. One man who joined Illustrious after the war recalls seeing much evidence of the damage done to the ship off Malta and then again while undergoing emergency repairs in Malta.

Yet, even at the war’s end, new ships were joining the fleet. One of these was the last battleship of the Royal Navy, HMS Vanguard, with eight 15in guns in four turrets. Serious consideration had been given to converting the ship before completion as an aircraft carrier, but this would have been a costly operation and the end result would have been too narrow in the beam to make an ideal carrier. The question was, of course, why was anyone ordering a battleship at this time? However, tradition dies hard and for the navies of the day, possession of a battleship was seen as a necessary status symbol. Many minor navies, especially in Latin America, kept battleships for many years afterwards, while others – for example, the Dutch, Australian, Canadian and Indian navies – all preferred the ‘modern’ option of an aircraft carrier.

While none of the Colossus and the extension of this class, the Majestic -class, ships saw action in the Second World War, they were involved in the Korean War and two saw service in Operation MUSKETEER, the Anglo-French invasion of the Suez Canal Zone. More enduring was that having ordered these ships in large numbers, especially for ships of their size, many were immediately available for sale or transfer elsewhere. These two classes saw service with the navies of Argentina, Australia, Brazil, Canada, France, India and The Netherlands, and in some cases introduced these navies to carrier-borne air power for the first time.

As many as possible of the Lend-Lease auxiliary or escort carriers were returned to the United States but some were in no state to go back, with Dasher having blown up killing many of her ship’s company and others sunk or so badly damaged that they had to be scrapped and another, Biter , was loaned to the French as the Dixmude . Nairana , one of the few British conversions, was loaned to the Dutch as the Karel Doorman , the irony being that the want of air cover had seen the loss of the admiral of this name with his ship in the Battle of the Java Sea. The Dutch subsequently received a Colossus -class light fleet carrier, Venerable , and after returning Nairana to the Royal Navy their new ship was named Karel Doorman .

As the Royal Navy was run down from its wartime strength, the naval bases around the world filled up with redundant escort vessels, especially corvettes. Other ships were sold off. While many of the escort carriers returned to the United States were converted to merchant vessels, strangely few of those operated by the USN were converted. The Royal Navy kept one of the British conversions, the Pretoria Castle , for many years as a trials ship.

There were some problems with personnel, with those of the wartime ‘hostilities only’ category expecting to be released as soon as the war ended, but this was impractical. Nevertheless, the Royal Navy did not suffer the indiscipline, almost amounting to mutiny, that affected many Royal Air Force bases, especially in the Indian subcontinent.

One naval pilot, a lieutenant commander, managed to switch from the RNVR to the regular service, but was then disappointed to find himself demoted to lieutenant and left waiting for weeks for a new posting. Nevertheless, when he eventually did retire many years later it was as a captain. Less fortunate were those caught in training as pilots or observers when peace was declared. While still not commissioned as this did not come in wartime until flying training was completed, they found themselves posted to be trained as aircraft engine mechanics and all hopes of early commissioning lost. Worse, on being posted for training, their superior ‘officer potential’ led to extra harsh discipline being imposed on them until the newspapers found out about it.

The Post-WWII Navy

In contrast to the situation earlier in the century, the post-war Royal Navy included many national servicemen, although less than the Royal Air Force and far less than the British Army. Of those who did find themselves undertaking national service with the RN, many were Merchant Navy personnel whose national service had been deferred until their training was completed.

A substantial Royal Naval Reserve and Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve were both maintained for many years until eventually these two categories were merged into a single Royal Naval Reserve. As the future of the Royal Navy was planned by an Admiralty committee known as the ‘Way Ahead Committee’, flying training for reservists was dropped, and eventually as the service contracted and national service ended, the RNR was mainly tasked with minesweeping. Other cuts saw the last battleship, Vanguard , first as the headquarters of the RNR and then eventually scrapped. Warspite had been withdrawn for scrapping soon after the war had ended and showed her displeasure by breaking her tow and ending up beached in St Michael’s Bay in Cornwall; Vanguard did the same, but off Southsea.

Aerial view of the Royal Navy aircraft carrier HMS Victorious (R38), taken circa 1958-1960, when the Royal Navy operated the Douglas Skyraider AEW.1.

The wartime aircraft carriers eventually were scrapped, except for Victorious which underwent a massive rebuilding to emerge with a half-angled flight deck and three-dimensional radar in the late 1950s, but she too was scrapped a few years later after a fire while under refit. Nevertheless, by the mid-1960s the Royal Navy had five aircraft carriers and two commando carriers. The latter were equipped with helicopters and could take a Royal Marine Commando brigade wherever it was needed; a legacy of the Suez campaign when the Royal Navy flew off the first heliborne assault.

Naval bases were cut. While the former RAF base at Hal Far in Malta was transferred to the Fleet Air Arm as HMS Falcon , the 1970s saw the Royal Navy’s presence run down and the base eventually closed as the Royal Navy left Malta after more than 170 years. Other major bases that were abandoned included Singapore and later Hong Kong after the territory was handed over to the Chinese People’s Republic. Today, only Gibraltar remains of the overseas bases and there is no longer a Mediterranean Fleet or, even in its much-reduced state, a Home Fleet. The various overseas squadrons and stations have all gone. Chatham was the only one of the three manning ports to close but it was followed in the 1990s by Rosyth. Today, the Royal Naval Reserve also has all but disappeared and its various ‘divisions’, small outposts around the coast, have gone.

Naval aircraft also changed. The first generation of jet aircraft such as the Supermarine Attacker was soon followed by the de Havilland Sea Venom and Armstrong-Whitworth Sea Hawk, but in the 1960s there was a major step forward. Starting with the Blackburn Buccaneer and then joined by the American McDonnell F-4M Phantom, carrier-borne aircraft suddenly became comparable with those based ashore. No longer was there a significant performance gap between aircraft designed to take off from ships and those based ashore. Both aircraft were also to see air force service.

The threat from low-flying aircraft also ended with Airborne Early Warning (AEW) aircraft such as the Fairey Gannet, a development of the Royal Navy’s last fixed-wing anti-submarine aircraft, while this role passed to increasingly powerful and effective anti-submarine helicopters such as the Westland Sea King and later the Agusta-Westland Merlin.

The 1970s almost saw the end of the aircraft carrier with the previous decade having seen replacements, known as CVA.01 and CVA.02, for the Royal Navy’s two largest carriers, Ark Royal and Eagle , cancelled. Ark Royal and Eagle were modified, with the former able to operate McDonnell Douglas F-4M Phantom fighters, and their lives extended. A complete end to British fixed-wing naval aviation was avoided when the Hawker Siddeley Kestrel vertical take-off aircraft appeared and this evolved into the British Aerospace Sea Harrier, while the concept of the ‘through deck cruiser’ emerged as a cut-price light fleet aircraft carrier. The discovery that a Sea Harrier had a much greater range or warload when using short take-off aided by a ramp known as a ‘ski-jump’ settled the shape of British naval aviation, and also that of Spain and Italy, for some years.

The ski-jump was not the sole British contribution to carrier aviation. British naval officers had invented the angled flight deck that allowed aircraft to land and take off at the same time, and allowed a pilot landing to go round for another attempt if necessary. The mirror-deck landing system was another of these inventions that helped aircraft to land, while the steam catapult enabled ever-heavier naval aircraft to take off safely.

In the end, three ships of what was known as the Invincible class were built. The conversion of the Centaur -class carrier Hermes as an interim ‘Harrier Carrier’ and the delivery of the first Invincible -class carrier meant that the Royal Navy was able to recover the Falkland Islands which had been invaded by the Argentine Republic in 1982. Unfortunately, only two of the Invincible -class ships, Illustrious and Ark Royal , were kept in commission and then the Sea Harriers were scrapped, although of a more up-to-date mark than those that had rescued the Falklands. After that the remaining carriers were withdrawn, although Illustrious received a temporary reprieve as a helicopter carrier. In the meantime, the remaining Harriers were jointly manned by Fleet Air Arm and RAF personnel as ‘Joint Force Harrier’.

The number of escort vessels also fell sharply from more than 182 in 1958: first to around 80; then to 40; to 25 in 2008; and eventually to just 19 today. Escorts were no longer steam- or diesel-powered but powered by gas turbines and gradually all escorts had a helicopter landing platform and hangar with some of the Type 22 frigates able to carry two helicopters. In the interests of economy and extending range, later escorts were powered by diesel and gas turbine propulsion.

Mines are no longer swept, not even hunted and then swept, but instead are found by sonar with a remotely-controlled submersible used to destroy the mine. Meanwhile, mine countermeasures vessels (MCMVs) as they are now known are no longer built of wood but of glass-reinforced fibre.

The biggest change has been the introduction of the nuclear-powered submarine, of which the first in Royal Navy service was named Dreadnought . These vessels were initially all ‘fleet’ submarines or ‘hunter-killers’, meaning that their main role was to counter Russian missile-carrying submarines, but later the responsibility for Britain’s nuclear deterrent was passed from the RAF to the Royal Navy and four intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) Resolution -class submarines were introduced to carry Polaris missiles. There should have been five boats of this class but, with the nation ever more concerned about economics than defence, the fifth boat was cancelled. When Polaris was replaced by a more potent missile, Trident, the Resolution -class boats were replaced by the Vanguard class, also of four vessels.

The rank structure has also changed. The rank of commissioned airman or gunner that replaced the warrant officer rank was abolished in the mid-1950s and those holding this rank became sub-lieutenants, but change is often reversed and after the introduction of fleet chief petty officers, the rank of warrant officer has returned. At the other end of the scale, with all three services abolishing five-star ranks, there is no longer a rank of admiral of the fleet. Indeed, given the continued run-down of the Royal Navy, one wonders how much longer a First Sea Lord will be able to justify the rank of admiral?

At present the Royal Navy has the two largest aircraft carriers it has ever operated, the Queen Elizabeth and the Prince of Wales , under construction but there are no plans to operate both ships and in any case, there are insufficient escort vessels for both to put to sea safely in a potentially hostile environment. For the first time in history, the French Marine Nationale has more ships than the Royal Navy.