Lieutenant Colonel Les Andrew VC and the New Zealand 22nd Battalion at Helwan after their return from Crete, July 1941.

As the exhausted Anzacs stumbled off ships at Suda Bay and took stock of their new surroundings, the prospect of an epoch-making battle against German paratroopers was far from their thoughts. Most were intent on the simple necessities of food and sleep. The survivors from the Costa Rica were the worst off, having lost all their personal kit as well as their weapons when the troopship went down. Don Stephenson managed to acquire a greatcoat before he landed; apart from that, his earthly possessions on arrival at Suda Bay comprised a pouch of tobacco and a tin of sausages. Coming ashore, Stephenson walked down the jetty and straight into the arms of his brother, who was serving in another AIF unit. He remembered, ‘I hadn’t seen him in months, so we sat down and had a sausage and a smoke.’

For the Australians and New Zealanders, Crete would be a battle against military privation as well as against the Germans. Having lost his Lee-Enfield .303 rifle at sea, Stephenson was issued with an ancient ceremonial rifle used by the British Black Watch regiment, from which dangled a scabbard and bayonet, tied on with a piece of string. The remnants of Murray McColl’s platoon of New Zealand machine-gunners had one Vickers gun, but no tripod, so they got it ready for action by lashing it to the fork of a tree. For his own use, McColl acquired a rifle — without a bayonet — by visiting the British hospital near Suda Bay and taking one from a wounded patient. Phillip Hurst of the 2/7th Battalion was luckier. Like Stephenson, he lost all his gear on the Costa Rica, but on Crete he was issued with a new Tommy gun. Even this bounty had its limits — no replacement webbing accompanied the gun, so Hurst fashioned a substitute to carry his ammunition by tying two socks together and hanging the result around his neck.

Enterprise and improvisation were the order of the day. D Company, 2/1st MG Company added to its stock of Vickers guns by assembling one from the spare parts intended for maintenance purposes.2 Even the most specialised units had to scrounge and make do. The 4 Special Wireless Section got to Crete with most of its technical gear, save for the direction-finding equipment it needed to estimate the location of German transmissions. Its personnel fashioned replacements by salvaging equipment from the many ships lying half-submerged, sunk by German air attacks in the shallows of Suda Bay.3 The infantry did likewise, albeit more prosaically — without entrenching tools with which to prepare pits and trenches, many were dug with nothing more than a tin hat to scratch the ground.

Eric Davies of the 19 NZ Battalion recalled that his platoon, in trying to connect a trench system in an olive grove, spent a fortnight hacking through a massive tree root with nothing more than a bayonet. Davies had an axe to grind of a different kind: having survived his ducking in the Aegean weighed down by his assorted weaponry as he climbed aboard Kingston, he had to give up his spare rifle to the very man responsible for kicking him into the sea. The sacrifice had ‘grieved me ever since,’ Davies recalled 60 years later.

Not all of the defenders had been through the ordeal in Greece. A British brigade had been on garrison duty in Crete since November 1940, when Britain first began assisting the Greeks following the Italian invasion. A handful of Australians were also new to the fighting. A battery of the Australian 2/3rd Light Anti- Aircraft Regiment was landed in Crete to help defend the aerodromes. A Troop went to Maleme in the west, and the rest of the battery took up station at Heraklion in the east. This small reinforcement might have been fresh, but they were ill-prepared. One of its number, Ian Rutter, remembered that for some reason the regiment was a favoured destination for many sons of the Melbourne establishment, but their political connections did not guarantee adequate preparation. Although formed as a specialised anti-aircraft unit, the regiment had never fired its designated equipment, the 40-millimetre Bofors automatic cannon, before it went into action for the first time.

Ill equipped and scantily armed though they were, the Australians and New Zealanders were still fighting among friends, and they were grateful for it. Ken Johnson, at the head of his platoon in the 2/11th Battalion, sent foraging parties to nearby villages to buy milk, honey, and cheese to supplement the army diet of bully beef. Eric Davies confided to his diary on 29 April that although he ‘spent a mighty cold night without a greatcoat’, the hospitality of the Cretans was excellent compensation: ‘I’ve had more to eat today than for weeks. Eggs and chips, after weeks of hard ration, were a splendid feast.’ Phillip Hurst, entrenched along with the rest of the 2/7th Battalion at the village of Georgiopoulos on the island’s mid-north coast, remembered the kindness of the Cretans for the rest of his life:

We wanted some honey, so we went up to the village and asked them, and a chap said a lady there kept bees. But she didn’t have any containers. Well, if we promised to bring the container back, a two-pint billy, a nice one, we could have some honey, and she wouldn’t take the money. That was on the nineteenth of May — we never ate the honey, and never took the billy back. Memories. Life goes on.

Given the length of time that passed between November 1940 when the first British troops landed in Crete, and the German invasion six months later, the improvisations and lack of training were scandalous. Little had been done to prepare the island, because Crete was thought of as a convenient base and depot site for operations on the mainland. One of the consequences of this mentality was that the three British battalions of the original garrison were ‘placed where administration was easy, water plentiful and malaria absent’. Convenience and comfort are not often sound military virtues, nor is constant reorganisation. In this case, a succession of British officers were given command of the garrison before Greece fell and, as result, none had sufficient time in which to prepare a coherent defence plan. The last of these temporary commanders was Major General Weston — his unit was the Mobile Naval Base Depot Organisation (MNBDO), which was landed in Crete in echelons from January 1941. The deployment of this unit says much about how the British leadership conceived of Crete. Planned between the wars as an infrastructure organisation to quickly establish a fleet base for the Royal Navy in a far-flung part of the world, the MNBDO was well equipped with anti-aircraft and anti-submarine defences, but it was essentially a garrison formation with a multiplicity of depot units, having little or no capability to fight in the field.

Weston himself only took up command in Crete on 26 April. His tenure lasted but four days before he was replaced by Bernard Freyberg, who arrived at Suda Bay with his staff after their evacuation from Monemvasia. Freyberg thought he was only staging through to Egypt; instead, to his considerable surprise, at a conference held on 30 April with Wavell, he was given command of the defending forces on Crete. The first obstacle that Freyberg had to overcome was his own ignorance, which he acknowledged in his campaign report:

The main defence problems which faced me in Crete were not clear to me at this stage. I did not know anything about the geography or physical characteristics of the island. I knew less about the condition of the force I was to command. Neither was I aware of the serious situation with regard to maintenance and, finally, I had not learnt the real scale of attack which we were to be prepared to repel.

Ignorance might well have been bliss because, as Freyberg’s knowledge grew, so too did his anxiety. British intelligence estimated that the Luftwaffe could deposit on Crete between 5000 and 6000 paratroops in a single sortie, giving the Germans the capacity to seize a decisive area and then reinforce it at will. Winston Churchill, fortified with brandy and cigars in his bunker below Whitehall, thought this a ‘fine opportunity for killing parachute troops’. But Freyberg, having read the intelligence report, concluded more soberly, ‘I could scarcely believe my eyes.’ Apart from the experience he had gained in Greece fighting the Germans, Freyberg was now also showing signs of developing a finer sense of political acumen. After receiving the London appreciation, on 1 May he appealed for equipment and stores not through military channels, but directly to his own government. This forced Churchill to cable Wellington on 3 May, assuring prime minister Peter Fraser that the necessary equipment would be sent to Crete.

Despite this political assurance, what Freyberg actually received was modest enough — apart from small arms, some transport and stores, up until the invasion his reinforcements amounted to two British infantry battalions, 16 light and six infantry tanks, and a troop of mountain artillery with eight guns. His request for field artillery was met by the delivery of 49 pieces, but these were decrepit Italian and French guns, often without sights and instruments, and not modern British 25-pounders.

Shockingly, while expert Australian and British gunners marooned on Crete were formed into improvised infantry companies, a sizeable stock of 25-pound guns remained safely in Egyptian depots — a decision that accorded with Churchill’s determination to resume the offensive in Libya as quickly as possible. The 2/2nd Field Regiment, which had fought with such distinction at Brallos, was one of the bereft artillery regiments on Crete: John Anderson remembers his battery had one rifle for each section of nine men, while Phillip Worthem had a Boys gun, but no ammunition. Without enough of the second-hand Italian and French guns to go round, Cremor — the regiment’s indomitable commander — tossed a coin for their possession with the 2/3rd Field Regiment. Cremor told his men it was a good toss to lose, and they went on with their few infantry weapons. The 5 NZ Field Regiment was one of the artillery units which took on ‘an odd assortment of guns’, including Italian 75-millimetre howitzers, about which the New Zealanders, of course, knew very little — including whether the guns would fire at all, what maximum range they possessed, and how the combination of the four charges they used would produce different ranges.

As the gunners set to work, Freyberg considered what to do with the sizeable Greek force under his command, placed at his disposal by the king and prime minister Tsouderos, who had arrived on the island before him. This force comprised 10,000 troops, organised in three regular battalions and eight recruitment units, and Freyberg was impressed by their determination, if not their training and equipment. He reported: ‘There is no doubt that the Greeks and Cretans were good material and, given the time, great things could have been done. In point of fact, the entire population of Crete desired to fight.’

#

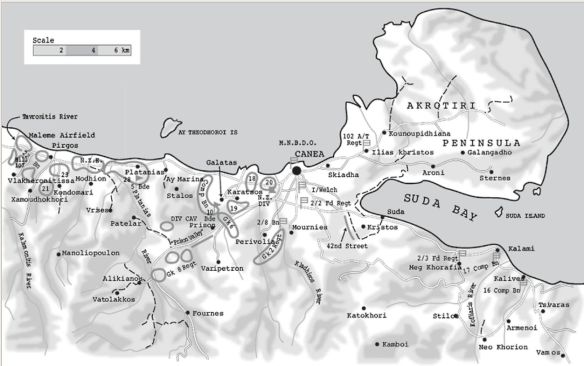

Despite the bravery of the defending gun crews, air operations are rarely defeated by anti-aircraft weapons in isolation. So it was on this occasion. With their supremacy in the air, the Germans could mount their paratroop assault at a time and place of their choosing. That moment came on the morning of 20 May 1941. The German invasion was mounted by three groups, and came in two waves. Against Maleme in the first wave, Student sent his Gruppe West, commanded by Major General Meindl and comprising an assault regiment with three-and-half battalions. The other element of this first wave came from Gruppe Mitte, led by General Leutnant Süssman, who sent the 3 Fallschirmjäger Regiment, half of I Battalion, Assault Regiment, and a pioneer battalion to take Canea and Suda. In the second wave, to follow in the afternoon, Student ordered the 2 Fallschirmjäger Regiment (less one battalion) from Süssman’s Gruppe to take Retimo, and committed his Gruppe Ost, under Ringel, to seize Heraklion airfield using the 1 Fallschirmjäger Regiment, II Battalion of the 2 Fallschirmjäger, and the 5th Gebirgs Division, supported by the II Battalion, 31 Panzer Regiment. Student was forced to mount Merkür in two waves for want of sufficient transport aircraft to do the job in one; his decision to then spread the landing over widely separate points nearly brought the operation undone.

In considering how to meet this assault, Freyberg had access to unprecedented intelligence, thanks to the British code-breakers who could read the German Enigma transmissions. ‘Ultra’ informed Freyberg on 13 May that attempts to seize the aerodromes by paratroop landing would be followed by a seaborne invasion; from this, the defenders should have concluded that if they could hold the airfields, Merkür must fail. Given the availability of this information, Freyberg’s preoccupation with the threat from the sea was unfortunate.

When it came, the German attack provided a spectacle that none of the surviving Australians and New Zealanders would ever forget. The assault opened with a concentrated blitz by German bombers and fighters on the anti-aircraft defences and those field works that could be discerned from aerial reconnaissance photos. Murray McColl, with his composite unit above Galatas, was eating his breakfast porridge out of a dixie just before seven in the morning, when he was forced to take cover by the raiding aircraft. Six Messerchmitt fighters broke off in a determined attack on his position and, despite the savagery of the raid — so intense that McColl remembered, ‘I wasn’t frightened, I was bloody well petrified.’ — he and his comrades thought that once the attack was past they could go back to breakfast. ‘Thank God that’s finished,’ McColl remembered thinking, until one of his comrades asked, ‘What’s that buzzing noise?’

Many of the defenders recalled that distant hum, like bees, growing louder as the dark spots on the northern horizon resolved themselves into hundreds of tri-motor Junkers transports, 80 of them towing DFS 230 assault gliders. On their way to Crete, the gliders passed over Athens, where onlookers thought they resembled ‘young vultures following parent birds from the roost’. When they arrived at Maleme, the metaphor was apt, as the dazed anti-aircraft gunners watched an ‘extraordinary sight’ unfold: ‘the air was full of parachutes, with a complicated system of colours, officers one colour, supply canisters another, this great concentration of parachutes in the air.’ Frank Sherry, with his code-breaking unit above Suda Bay, found the sight ‘demonic’, while McColl likened the paratroopers to ‘men from Mars’.

Allusions to science fiction figure often in the memories of survivors from that day, and for good reason — nothing on this scale had ever been seen on a battlefield before. Until that moment, many shared the view of Eric Davies, who remembered, ‘We thought it was bullshit, we couldn’t see how they could land thousands like that.’ The shock of the assault when it came was profound.

Even so, when the defenders recovered their equilibrium, the consequences for the German paratroopers were hideous. For all its bravado, a paratroop attack on a prepared position is an extraordinarily vulnerable undertaking. The Junkers transports made their dropping runs at not much more than 100 metres, at relatively slow speeds. As a result, the aircraft were well within range of even small-arms fire, and the paratroops themselves, once in their harnesses, spent anxious moments descending to earth —easy targets even for inexperienced riflemen. The German harness design didn’t help the paratroopers avoid the defences or the obstacles: it suspended the parachutist from a single strop, which meant that the camopy could not be steered in any way.

Unfortunately for the Germans, many of the defenders were battle-hardened, expert infantry, not the disorganised remnants from Greece that German intelligence had assumed. Malcolm Coughlin and his platoon of the 19 NZ Battalion were entrenched on a ridge above Galatas, looking toward Cemetery Hill. Coughlin was armed with a Bren gun, and could not believe the Junkers passing across his left flank, level with his position. At ranges of only 50 metres, Coughlin poured fire into the lumbering transports, and was easily close enough to see his rounds striking each plane as it passed.

Not all of the defenders took the opportunity presented. At Georgeopolis, Phillip Hurst had left his foxhole to fetch some water. Although the Germans made no landing there, he recalled that troop planes went right overhead. ‘We had to go and get water, and I was getting it, like a good soldier! I left my gun behind, [and was] caught in the open — three planeloads going overhead and no gun!’

The savagery of the defending fire naturally dislocated the German landings, and a number of Student’s units came to earth far from their designated drop-zones. The confusion in the German ranks began early: the glider carrying Süssman, commander of Gruppe Mitte, was destroyed in a crash near Athens, and the general and some of his staff were killed. The fragility and inherent danger of the technology used by the Luftwaffe was obvious to the defenders. Murray McColl recalls one transport flying by, with a paratrooper ensnared by his chute on the tailplane. The poor soldier spun wildly, ‘dangling, like [a] fly in the web, until finally he broke off and down he came — everyone cheered’.

The DFS 230 assault gliders afforded the Germans little more protection in the attack phase than the paratroopers enjoyed. Eric Davies found the noiseless descent of the gliders eerie, as they circled about looking for landing places, but their light construction left the occupants onboard vulnerable to ground fire and to bad landings on rocky or tree-covered ground. Five of the DFS 230s came down near Frank Sherry’s signals unit and, although Sherry was ‘seedy’ from the previous night’s celebration of his nineteenth birthday, he and his comrades quickly took advantage — ‘Even a .303 [rifle] made the gliders jump visibly in the air,’ he recalled. This flight of Germans landed successfully within 50 metres of Sherry’s billet but, according to him, ‘out of those five, not many came out alive.’ Despite the initial success of the signallers, four men ventured out to inspect their handiwork and look for souvenirs: one was killed, and the other three wounded and captured.

At Maleme, the airfield was held by just Leslie Andrew’s 22 Battalion of the 5 NZ Brigade, which blunted the drive of the 2nd Panzer Division through the Olympus Pass, but was now down to only 600 men. The allocation of this scant force to the decisive point would be Freyberg’s fatal miscalculation. He opted to organise his defence against both air and seaborne invasion, and the attempt to hold the coast saw the greater part of the 5 NZ Brigade deployed east of the aerodrome, from the village of Pirgos along to Platanias, which was garrisoned by the redoubtable Maoris of the 28 Battalion. With the Royal Navy still in command of the sea, Freyberg could have concentrated on the airfields. As it was, just a single infantry battalion and the anti-aircraft gunners held the vital aerodrome at Maleme and, despite the losses they inflicted on the Germans, the defenders were spread far too thinly. The defences there were also badly organised: despite repeated requests, the 370 men of the RAF, MNDBO, and the Fleet Air Arm who were camped on the airfield were not under Andrew’s command. ‘They retained their independence almost to the point of absurdity: even the current password differed among the three groups,’ wrote the 22 Battalion historian. The New Zealanders were unable to dig a continuous line along their western flank because it would have run through the British officer’s mess — an ‘unthinkable’ prospect, according to the battalion history.

The air attack on the 22 Battalion prior to the German landing was a foretaste of things to come. It killed five men of C Company on the airfield, and wounded Andrew at his headquarters. He described the hit as ‘a wee piece of bomb that stuck in above the temple’; when he pulled it out, it was ‘bloody hot and bled a bit’. The paratroop landing then followed, and the decisive element of the German attack proved to be a concentrated glider landing in the dry bed of the Tavronitis River, on the western perimeter of the airfield. There, 14 gliders came down and, along with other troops dropped by parachute, their occupants quickly besieged the New Zealand defence along the western fringe of the aerodrome. This comprised only one unit, 15 Platoon of C Company under Lieutenant R. B. Sinclair, a clerk from Waipawa. With just 23 men to hold a long stretch of river bank, Sinclair’s chances of defeating several hundred elite paratroopers were slim, particularly given the paucity of firepower available to him: in the whole of C Company, there were no mortars of any kind, and just seven Bren guns and nine Tommy guns, supplemented by six Browning machine-guns salvaged from wrecked RAF planes.

Other Germans landed on the west bank of the Tavronitis and, after forming up, made for the bridge, getting across it by dodging from pylon to pylon. Once on the eastern side, they entered the RAF camp on the southern edge of the airfield, and quickly put the bewildered air-force mechanics and ground personnel to flight. This thrust cut between Sinclair’s men and D Company under Captain T. C. Campbell, a farm appraiser from Waiouru. Campbell’s men were strung out between the aerodrome and Hill 107, garrisoned by Andrew’s A Company.

The German wedge into the RAF camp enveloped what was left of the 15 Platoon on three sides. The bravery of Sinclair and his men was reflected in their casualties. Sinclair himself fought on, though wounded in the neck; he was captured after he fainted from loss of blood. Nearby, Lance Corporal J. T. Mehaffey, a Wellington civil servant, gave his life for his comrades: when a German stick grenade lobbed into their weapons pit, Mehaffey put his tin hat over it and stood on the helmet while the grenade exploded. He died from horrific injuries when the explosion blew off both his legs. The 15 Platoon gamely held on until dusk. Of Sinclair and his 23 men, eight were killed, fourteen others wounded, and just two came out of the battle unhurt.

Elsewhere, the Germans landed directly on the battalion position, including the village of Pirgos, but the New Zealanders were able to eliminate these threats. On the airfield itself, however, the paratroopers were able to cross the runways, and bring the anti-aircraft gun crews under small-arms fire. Ian Rutter was among these men who, for want of small arms, were unable to defend themselves. The Bofors cannons taken over by the Australian gunners were fixed on concrete mountings — had they still been mounted on wheels, the gunners might have been able to drag them into the open and chop up the German infantry moving across the aerodrome. As it was, the static Bofors had to be abandoned, and Rutter and his surviving comrades were driven up Hill 107 with the remnants of the 22 Battalion, one of the four gun crews having been killed.

East of the aerodrome, the 5 NZ Brigade held its ground comfortably on the first day. The 23 Battalion overlooked the main coast road to Canea, with the 21 Battalion on higher ground south of it. As a result, the gliders and paratroops landing on the 23 Battalion fell on a strong position and were shot down in droves, with an estimated 400 killed.

To the south-east of Hill 107, along what the New Zealanders knew as Vineyard Ridge, the 21 Battalion was but a shell of the unit which had fought at Platamon and Pinios Gorge. It got to Greece with just 237 men, and more trickled in over the following weeks, including 39 who arrived on 3 May, led by Battalion CO ‘Polly’ Macky. His health was now scarred by the pressures of the campaign on the mainland, and on 17 May he handed command of the battalion to Lieutenant Colonel J. M. Allen, a ‘short, slight and wiry’ farmer, and member of parliament for Hauraki.

Allen’s new command easily accounted for 100 paratroops landing on the slopes around the battalion position, despite the fact that its machine-guns were antique Lewis guns. Now was the time for a counterattack to restore the position on the aerodrome, but poor communications eroded effective control of the battle. Signal lines to Puttick’s divisional headquarters were cut for most of the morning, and contact with individual battalions was minimal throughout the day. Left to their own devices, the local counterattacks organised by the New Zealand battalion commanders were half-hearted, lest they compromise the continuing defence of the ground they already held.

Andrew, at the head of the 22 Battalion, sent two Matilda tanks and a platoon of infantry against the aerodrome just after 5.00 p.m. In the first example of the generally poor performance of the British armour on Crete, one tank pulled out early with an unserviceable gun, and the other got as far as the Tavronitis, where it became bogged and was abandoned by its crew. In the chaos of air attack, confused fighting, and non-existent communications, Andrew struggled to maintain control of his battalion: during the night, patrols were sent out to find his A, B, and D companies, without success.

Behind Andrew, Allen had authority to act according to one of three scenarios: join the 22 Battalion along the Tavronitis; take over the ground of the 23 Battalion if it moved in support of the 22 Battalion; or stay where he was. Uncertain of the situation around him, Allen understandably opted to keep the 21 Battalion largely where it was, sending just a platoon to clear the villages of Xamoudhokhori and Vlakheronitissa. With more strength, this move might have re-established contact with the 22 Battalion on Hill 107; but, while Allen’s men got through Xamoudhokhori, they found the second village too strongly held, and the isolation of the defenders on Hill 107 remained.

Ian Rutter was one of those defenders, and he spent an anxious night with the Germans in close proximity on the slopes below. The New Zealanders had a listening post 30 to 40 metres in advance of their main position, and Rutter had to take his turn to man it. As they had in Greece, the Germans called out in English in an attempt to deceive the defenders into error:

[S]omebody had to wriggle out there and just listen. You could hear them talking, one German calling out, ‘Hello, Charlie? Is that you?’ It was eerie to be that close to them.

Towards dawn, the 22 Battalion was largely surrounded, and Andrew opted to salvage what he could of his unit, ordering a withdrawal. Ian Rutter went with the surviving New Zealanders, taking off his boots to dull the noise of his footfall. As his weary column moved back, he recalled, ‘The sun came up, and hundreds of fellows were sitting just waiting for an order’. While the hours ticked away, the Germans poured reinforcements into Maleme.