On June 9, 1982, three days after the start of the first Lebanon War, IAF pilots waited with great tension and suspense for the signal to embark on one of the air force’s most complicated missions: attacking Syrian missile batteries in Lebanon’s Beqaa Valley. In Jerusalem, the government continued to discuss the operation, struggling over fears of an escalation with the Syrians, who were politically and militarily involved in Lebanon. The debate was tense and stretched on for many hours. The time set for the start of the operation was pushed back, and Air Force Commander David Ivry retired to his office to concentrate on the latest flashes from the battlefield. Colonel Aviem Sella, the head of IAF operations, circulated among the pilots, checking their readiness, providing encouragement and trying to ease the tension.

At 1:30 P.M., IDF Chief of Staff Rafael Eitan called the air force commander from the prime minister’s office, telling him, “Time to act. Good luck!” At two, the offensive got under way.

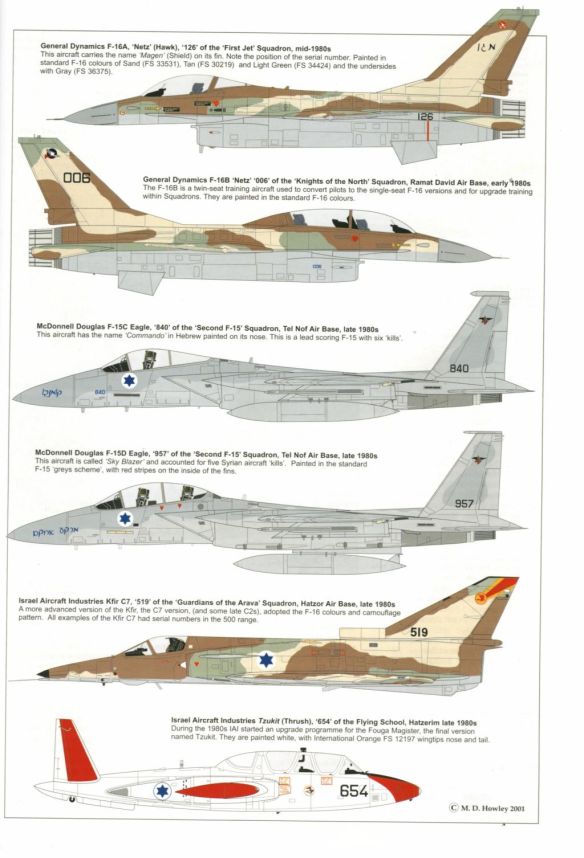

When the green light was given, twenty-four F-4 Phantom jets from IAF Squadron 105 took off, armed with missiles. Soaring alongside them were Skyhawk fighter aircraft, Kfirs—Israeli-made combat jets—and F-15s and F-16s armed with heat-seeking air-to-air missiles. For Israel’s electronic-disruption effort, the air force had enlisted Hawkeye early-warning aircraft, Boeing 707s and Zahavan drones. At the peak of the action, approximately one hundred Israeli planes were in the air.

The Syrians likewise threw roughly one hundred aircraft into battle—MiG-21s and -23s. Nineteen surface-to-air-missile batteries had been spread across the Beqaa Valley, where they were ready to launch SA-3, SA-6 and SA-8 surface-to-air missiles, among the most advanced, state-of-the-art engines developed by the Soviet Union.

Surface-to-air missiles were still a source of trauma for Israel’s air force. The war of attrition with Egypt, followed by the Yom Kippur War, had left behind bad memories and a sense of powerlessness against Egyptian missiles. The former defense minister, General Ezer Weizman, had coined the famous phrase “the missile that bent the plane’s wing,” which had motivated IAF commanders to look for a solution to this difficult problem. For five years, the top minds in the air force had labored with members of the military industry to develop a technological response that would protect the planes from the enemy’s missiles and bring the plane’s wing back to its natural place.

Now the hour of judgment had arrived: Would the Jewish brain again come up with an answer? Would the pilots’ nightmare come to an end? Would the IAF reestablish control over the region’s skies?

The attack’s opening move was the launch of drones over the Beqaa Valley, an act of misdirection. The aircrafts’ radar profile had been designed to resemble that of fighter jets, and the Syrians fell into the trap. As Israel’s military planners had thought, the Syrians immediately launched surface-to-air missiles at the drones, exposing the precise locations of their batteries, which in turn became targets for Israeli radiation-seeking missiles. Simultaneously, the IDF ground electronic sensors pinpointed the batteries’ locations and its artillery began shelling them.

Twenty-four Phantoms then suddenly appeared, each carrying two “Purple Fists,” anti-radiation missiles that zero in on radar installations by detecting the heat from antiaircraft systems. The planes launched the missiles at the batteries from nearly twenty-two miles away; also fired were Ze’ev surface-to-surface missiles, a sophisticated short-to-medium-range weapon that had been developed in Israel. The entire time, drones circled above the area, transmitting the results back to the operation’s commanders.

After the attack’s first wave, the Syrian batteries went silent for several minutes, and then the second wave arrived. Forty Phantoms, Kfirs and Skyhawks fired various types of bombs, among them cluster bombs that destroyed the batteries and their crews. The third wave took on the few remaining batteries, and within forty-five minutes, the attack had ended as a complete success. Most of the batteries had been wiped out.

During the offensive, the Syrians had fired fifty-seven SA-6 missiles but had managed to hit just one Israeli plane. For several long minutes, the Syrian command had been in complete disarray, and when it realized its battery system had collapsed, scrambled its MiGs. During the aerial battles that ensued, Israel’s F-15s and F-16s brought down twenty-seven MiGs using air-to-air missiles.

“From an operational standpoint, in contrast to what was planned, the attack on the missile batteries was one of the simplest missions I ever oversaw,” said Colonel Sella, who had been charged with the operation’s ground management. “Everything went like clockwork. As a result, even after the first planes successfully attacked the batteries, I ordered their continued bombing. The perception was that any change, any pause or shift, could only create turmoil that would disrupt the progression of matters.”

Toward 4:00 P.M., Sella reached a decision that he later described as the most significant of his life: to halt the operation. “At this stage, we had already destroyed fourteen batteries. We were an hour before last light, and we hadn’t lost a plane. I believed we couldn’t achieve a better outcome. When I leaned back for a minute in my chair, I took in some air and said to myself, ‘Let’s stop—we’ve done our work for the day. They’re going to bring more batteries tomorrow in any case.’”

Sella went to David Ivry, who was observing the mission with Chief of Staff Eitan. Sella leaned into Ivry’s ear so that Eitan wouldn’t hear and said, “I’m requesting authorization to stop the operation. We won’t accomplish more today. We’ll destroy the rest tomorrow.”

Ivry thought for a moment and nodded in agreement. The handful of planes then en route to an additional attack returned on Sella’s orders to their bases. Defense Minister Ariel Sharon didn’t love the decision, to put it mildly, even criticizing it harshly during a meeting with Eitan. But Sella’s theory that the Syrians would move additional batteries to the Beqaa Valley overnight proved correct.

Over the next two days, Israeli bombers, escorted by fighter jets, set out to strike the new SA-8 batteries relocated by the Syrians. Because of the paralysis of Syria’s defensive batteries, its air force dispatched planes to intercept the Israeli aircraft. In the battles that followed, Israel’s pilots again had the upper hand: eighty-two Syrian aircraft were downed over the course of the first Lebanon War. The Israeli Air Force lost two planes to ground fire. During the campaign, what became known as the “biggest battle of the jet age” took place, involving approximately two hundred planes from the two sides.

“This situation, in which our planes were dominant and the Syrians were in a state of panic, gave us a huge psychological advantage,” Ivry said. “The aerial picture on the Syrian side was very unclear. We added in electronic means for disrupting their ability to aim and keep control, meaning that the Syrians entered the combat zone more as targets than as interceptors.”

When Ivry, who had also been the air force commander during Israel’s attack on Iraq’s nuclear reactor, was asked what his most exciting moment had been, he answered without hesitation that it was the end of the missile attack during the first Lebanon War. “When it became clear that we had succeeded in destroying the Syrian missile apparatus and that not one of our planes was damaged, it was a moment of true spiritual transcendence. This was a struggle involving the entire air force—a big concert with lots of instruments of various types, and everyone needed to play in perfect harmony.”

The operation’s success gave Israel complete control over the skies of Lebanon and made it possible for air force planes to freely assist IDF ground forces. Nevertheless, the air force abstained from striking Syrian ground troops, in keeping with a decision made by the cabinet, which feared sliding into an all-out war with Syria. On June 11, 1982, following mediation by the American emissary Philip Habib, a cease-fire between Israel and Syria took hold.

The mission, Operation Mole Cricket 19, was considered one of the four most important in the history of the air force. (The other three were Operation Focus, the assault on the combined Arab Air Forces during the Six Day War; Operation Opera, the attack on the nuclear reactor in Iraq, in 1981; and Operation Yonatan, the rescue of hostages in Antebbe, in 1976.) Western air forces regarded the mission as an example of the successful use of Western technology against Soviet defense strategy. The results of the attack caused a great deal of astonishment among the military leaders of the Warsaw Pact, overturning their sense of confidence in the USSR, and particularly in the Soviet bloc’s surface-to-air-missile apparatus.

AVIEM SELLA, SQUADRON COMMANDER

“For the sake of this operation, we developed, with the help of a great team of scientists from the Weizmann Institute, a computerized control and planning system that would make it possible to prepare and command a multivariable campaign: to manage hundreds of planes with hundreds of weapons facing dozens of missile batteries and dozens of radar installations. It was a dynamic system operating in real time with thousands of variables. The primary and most outstanding programmer was a Haredi [Orthodox Jew] who lived in Bnei Brak, Menachem Kraus, who had no formal education but immense and unique knowledge. He was involved in all of the operational programs and, at the moment of action, sat with us in the Pit, in his civilian clothes.

“At the end of the day, we would conduct a nighttime debriefing and discuss what we had learned. I arrived at one debriefing where all the squadron commanders were participating, as well as all the wing commanders and former air force commanders. And, all of a sudden, everyone is standing and starts to applaud me for the perfect operation. I was very moved, because this sort of thing is quite rare in the middle of a war. I also got a little statuette, which was inscribed, ‘To Sella, the thinker behind the fight against missiles, your vision has been fulfilled and we’re standing tall once again—the fighters of Air Force Base 8.”