The practical outcome of this meeting was a group of diplomatic instruments which have come to be called collectively the Treaty of Picquigny of 29 August 1475. Its terms, which were to govern Anglo-French relations until almost the end of Edward’s reign, may be summarized as follows:

1.A truce between the two kings and their allies to last for seven years, until sundown on 29 August 1482.

2.Freedom of mercantile intercourse for the merchants of each realm in the other’s countries, with the abolition of all tolls and charges imposed upon English merchants during the previous twelve years, and similar privileges for Frenchmen trading in English territory.

3.Edward was to depart peacefully from France as soon as he had received the 75,000 crowns, promised by the French king, leaving behind him John, Lord Howard, and Sir John Gheyne as hostages for his speedy return.

4.Any differences between the two countries were to be referred to four arbitrators, Cardinal Bourchier and the duke of Clarence for England, and the archbishop of Lyons and the count of Dunois for France.

5.A treaty of amity and marriage. Neither king should enter into any league with any ally of the other without his knowledge. As soon as they reached marriageable age, the Dauphin Charles should marry Elizabeth of York, with a jointure of £60,000 yearly provided by King Louis, and her sister, Mary, should take her place should Elizabeth die. Further, if either king found himself confronted by armed rebellion, the other must lend support.

6.An undertaking by King Louis to pay Edward 50,000 gold crowns each year in the city of London, by equal instalments at Easter and Michaelmas, and a guarantee for the payment of this pension either in the form of a bond by the Medici bank or a papal bull imposing interdict on his realm if he defaulted.

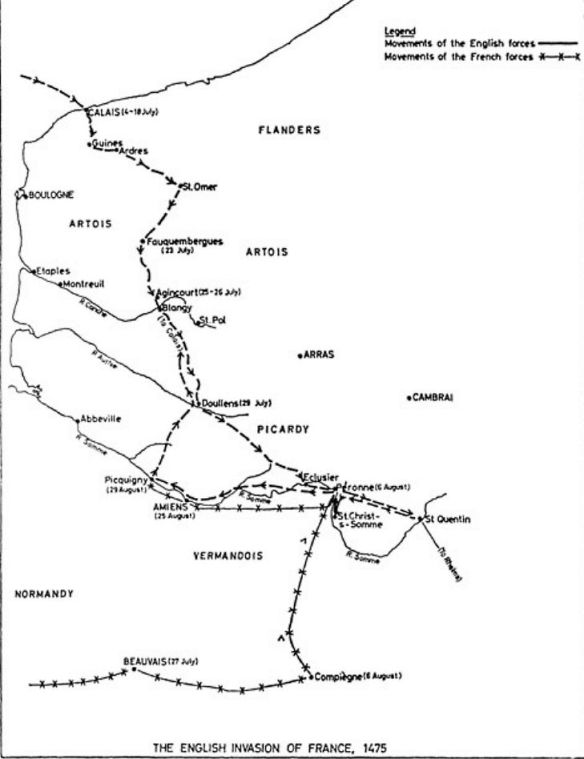

Edward lost no time in carrying out his first commitment under the Treaty. Having collected 55,000 crowns of his initial Danegeld, he accepted a bond under the great seal of France for the remainder, and at once the English army began its march to Calais, which it reached without serious incident on 4 September. Its transshipment to England began forthwith. Edward himself lingered in Calais until 18 September, and he did not return to London until 28 September, to be escorted through the city by the mayor and aldermen and 500 members of the guilds. The ‘great enterprise’ was over.

It was scarcely to be expected that the inglorious outcome of the 1475 expedition would be popular with the mass of Edward’s subjects. His leading captains and councillors had solid inducements to approve their master’s policy. Like Edward, they were quite ready to accept pensions and gifts from the French king. John, Lord Howard, and Sir Thomas Montgomery got pensions of 1,200 crowns (£200), the chancellor, Bishop Rotherham, had 1,000 and John Morton, master of the rolls, 600. According to Commynes, further pensions were paid to the Marquis of Dorset, Sir John Cheyne and Sir Thomas St Leger. The largest pension of all went to the most influential of Edward’s councillors, William, Lord Hastings, who now received an annual fee of 2,000 crowns. But Hastings displayed a remarkable independence of mind, and even this large sum did not buy his goodwill, for he afterwards took a notably individual line on the problem of the Burgundian succession. Nor was this all. Sparing no expense to win the good offices of influential Englishmen, Louis loaded them with presents of money and plate. Howard is said to have received as much as 24,000 crowns (£4,000) in this fashion within two years; Hastings had 1,000 marks’ worth of plate in a single gift, and many other English captains were among the beneficiaries. It would perhaps be too cynical to suggest that these were the only reasons why these royal advisers and servants so readily agreed to the abandonment of the campaign. The Croyland Chronicler, himself a councillor, regarded the treaty as ‘an honourable peace’ and observed that ‘in this light it was regarded by the higher officers of the royal army’.

But many outside the royal circle took a very different view. Amongst the soldiers of the army there was indignation at what they regarded as their leaders’ tame surrender to the French offers. Some took service with the duke of Burgundy to get the plunder and fighting for which they had come to France. A sense of disgrace and injured martial pride is reflected in the bitter words of Louis de Bretelles, a Gascon in the service of Earl Rivers, when he told Commynes that Edward had won nine victories and lost only one battle, the present one; and that the shame of returning to England in these circumstances outweighed the honour he had gained from the other nine. The king of France realized how sensitive were the English on this issue. He had jested incautiously that he had easily driven them from France with venison pasties and fine wines, and then became greatly concerned lest news should leak to the English of this mockery. But there was little he could do to check the jeers of his people. A version of the royal jibe became the theme of a popular French song:

J’ay vu le roy d’Angleterre

Amener son grand ost

Pour la françois terre

Conquester bref et tost.

Le roy voyant l’affaire

Si bon vin leur donna

Que l’autre sans rien faire

Content s’en retourna.

Similar taunts were thrown at the two hostages, Howard and Cheyne, who, after being royally entertained in Paris, accompanied King Louis to Vervins for the signing of a truce with Burgundy. When one of them commented on the large numbers of men in Charles’s train, the vicomte de Narbonne, who was standing nearby, remarked on the simplicity of the Englishmen in supposing that the duke had no troops at his disposal, but, he went on, ‘you English were so anxious to return home that 600 pipes of wine and a pension which the king gave you sent you post-haste back to England’. The angry Englishman replied that it was tribute-money, not a pension, and threatened that the English army might return. Even the count of St Pol, now desperate between the grindstones of Louis and Duke Charles, both of whom he had betrayed, could call Edward a poor, dishonourable and cowardly king.

Reactions in England were coloured not only by outraged national pride but also by resentment that so much public money had been spent to produce such an inglorious outcome. That Edward feared the hostility of his subjects is shown by his failure to make public much of the Treaty of Picquigny, especially the undertakings for mutual aid which he had exchanged with Louis, though news of both the French pension and the marriage alliance found its way into contemporary English chronicles. Rumours were rife on the Continent about the dangers which awaited Edward on his return home. Duke Charles was confidently predicting revolution when the English learnt what had happened. It was even said that Edward dared not let his brothers reach home before him, ‘as he feared some disturbance, especially as the duke of Clarence, on a previous occasion, aspired to make himself king’. The Milanese ambassador at the Burgundian court, Panicharolla, reported that the people of England were extremely irritated at the accord, ‘cowardly as it is, because they paid large sums of money without any result’.

In practice, these predictions proved to be wide of the mark, so far as may be judged from the meagre English sources of the time. Certainly, there was no outburst of resentment beyond Edward’s capacity to suppress. The Croyland Chronicler reports criticisms of the peace with France, and that disturbances following on the disbandment of the army forced Edward to make a judicial progress through Hampshire and Wiltshire in November and December 1475. He also expressed the opinion that it was as well that Edward acted speedily and vigorously to put an end to ‘this commencement of mischief’, for otherwise

the number of people complaining of the unfair management of the resources of the kingdom, in consequence of such quantities of treasure being abstracted from the coffers of everyone and uselessly consumed, would have increased to such a degree that no one could have said whose head, among the king’s advisers, was in safety; and the more especially those, who, induced by friendship for the French king or by his presents, had persuaded the king to make the peace previously mentioned.

There was enough resentment on this issue of waste of taxpayers’ money for Edward to feel compelled to remit the three-quarters of the fifteenth and tenth due for collection at Martinmas. With Louis’s cash in his pocket, and more to come, he could afford this gesture of pacification. But it is unlikely that he made any profit out of the war-taxation, as some continental critics suggested, and even more unlikely that (as Commynes believed) the hope of reserving to himself large sums from the proceeds of the taxes had been a major reason for his abandoning the campaign.

If Edward had failed to realize his proffered schemes of foreign conquest, he could at least claim that the settlement of 1475 brought substantial advantages for his countrymen. The implementation of the commercial agreement at Picquigny, and the removal of all the irksome and expensive restrictions on English trade with France, brought considerable benefits to English merchants and producers, especially those of the south-west, and made a contribution to the commercial prosperity of Edward’s later years no less important than the treaties with the Burgundians and the Hansards.

Indirectly, Englishmen also benefited from Edward’s French pension, which helped to make him largely independent of parliamentary taxation for the rest of the reign. Louis XI was at pains to ensure that the pensions to Edward and his councillors were promptly and regularly paid, despite the fact that they represented a heavy annual charge of 56,000 crowns – for he had not, in fact, bought peace with the English for the price of a few venison pies and consignments of wine. The royal revenue was further augmented by the somewhat cynical bargain between the two kings over the person of Queen Margaret of Anjou. Whether or not the question of her ransom was discussed at Picquigny we do not know, but arrangements were soon put in hand for her release from captivity. In September 1475, Sir Thomas Montgomery was sent to France to discuss terms. Edward was to surrender all rights over her, and transfer them to Louis in return for a ransom of 50,000 crowns (£10,000), of which sum the first 10,000 should be paid when Margaret was handed over, and the rest in annual instalments. She was also to agree to renounce formally all tide to the Crown of England, to her dower lands, and any other claims she might have against Edward. The transfer was completed at Rouen on 22 January 1476, after she had signed the necessary instruments of renunciation. But the unfortunate queen had merely exchanged one captor for another, and to obtain her liberty she had to give up all claims to the Angevin inheritance of her father, King Réné of Anjou, and her mother, Isabella of Lorraine. For the last six years of her life – she died on 25 August 1482 – she was wholly dependent on the modest pension paid her by the king of France.

Both the king and his subjects benefited substantially from the peaceful outcome of his French adventure. Its satisfactory if somewhat inglorious conclusion should not, however, be seen as any great tribute to Edward’s statesmanship. He had fully intended to mount a major military attack upon France, and, with Burgundian aid, to extract considerable territorial concessions from her king. Even if he did not seriously seek to make himself king of France, the defence of any continental conquests would surely have involved him in years of expensive warfare, as English experience under Edward III and Henry VI had proved. The days when England, even in alliance with Burgundy, could seriously challenge the most powerful and wealthy state in Europe were long since past. But only the unexpected failure of Burgundy to cooperate effectively in Edward’s plans enabled him to extricate himself sensibly and profitably. Peace with France, and the avoidance of expensive foreign entanglements, was achieved largely through good fortune rather than good judgement. Moreover, as the events of the next few years were to show, there was a price to be paid for the benefits won at Picquigny. Edward’s desire to retain his French pension and the French marriage planned for his daughter severely limited his freedom of diplomatic manoeuvre after 1475. They purchased English acquiescence in the partial dismemberment of the Burgundian state by Louis of France.