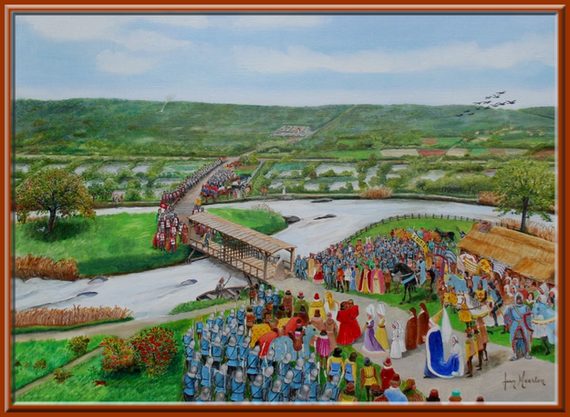

Peinture de Jean Maerten

Le 29 août 1475, le Traité de Picquigny met fin à la guerre de cent ans. Le Roi de France, Louis XI, et le Roi d’Angleterre, Édouard IV, décidèrent de se retrouver à Picquigny afin d’y signer le traité sur une petite île de la Somme que l’on appellera par la suite : « L’Île de la Trêve ». Les Français arrivent par la rive gauche et les Anglais par la rive droite. Les Anglais ont leur campement à La Chaussée-Tirancourt ; avant de rejoindre Picquigny, ils traversent notre village.

The ‘great enterprise of France’ began inauspiciously, with ten days’ loitering in Calais to await the coming of Duke Charles of Burgundy. His arrival with no more than a bodyguard at his back caused consternation in the English army. Some of the lords were for abandoning the invasion forthwith, but many of the rank-and-file, ‘studying glory rather than their own ease’, declared that they could manage perfectly well without Charles’s troops, and that they should carry on with the campaign they had come for. However much Edward may have shared his captains’ sentiments, he would have faced an uproar at home if he had given up his venture without ever leaving Calais. As with Henry V after his eventual capture of Harfleur in 1415, some military gesture was necessary to satisfy English public opinion. Probably mainly for this reason, he agreed to the duke’s proposal that the English should advance eastwards through his own territories to Péronne, then into France to the town of St Quentin, which the count of St Pol was still offering to deliver, and thence by way of Laon to Rheims. Charles himself promised to rejoin his army in the east, crush the duke of Lorraine, and meet the English forces in Champagne. The allies were fortunate in that King Louis’s main forces were in Normandy, and, even after he had learnt that the English had landed at Calais, Louis still believed that their principal attack would be directed southwards against Normandy, and took measures accordingly. Charles argued that the French army could cover only Normandy effectively and that St Quentin was the key to Champagne. Once in Rheims Edward might be crowned king of France and would soon win recognition as the country’s legitimate ruler.

On 18 July, therefore, the king and the duke led the English army from Calais through Ardres and Guines to St Omer, and thence, on 23 July, to Fauquembergue. Then two nights were spent at the historic site of Agincourt, and by way of St Pol they reached Doullens on 28 July. By now King Louis had divined the English plan, and, leaving a holding force in Normandy, set off with his main army on a route roughly parallel with the English line of advance. By the end of July, with some 6,000 men, he had reached Beauvais. On 1 August Edward and his army resumed their march in a south-easterly direction. Crossing the Somme they encamped on 5 August at Eclusier, a few kilometres from Péronne, with the river at their backs, and on the next day Duke Charles arrived in Péronne. There a messenger came in from the count of St Pol, expressing his continued willingness to deliver up St Quentin. But when an English detachment moved forward to the town, they were surprised to be met with cannon-fire from the walls and an attack from skirmishers. After losing a few men, the English withdrew and marched back through heavy rain to the army’s main camp, which was now (by 12 August) at St Christ-sur-Somme, just south of Peronne. As if this were not enough, there was now ill-feeling between Edward and Charles over the refusal of the duke to admit the English into any of his towns. Even the gates of Péronne, where the duke lay in comfort, were closed to his allies.

For Edward these irritations probably provided the final touch of disillusionment. His position gave little encouragement to pursue a bold policy. Behind him the French were already devastating Artois and Picardy, and provisions for the English army would soon become a problem. Ahead, Rheims and other French towns were now strongly garrisoned and fortified and on the alert. From a military standpoint, any further advance into France would be dangerous unless Duke Charles could guarantee much more active help. Summer was drawing to a close, but where were the English to find winter quarters if Burgundy denied them entry to his towns? Edward himself, who had little natural taste for campaigning, probably viewed the prospect of wintering in France with little relish. Nor had he the funds to keep his army in the field indefinitely. His captains, who had enjoyed no chance to enrich themselves or their men with plunder, may already have been chafing. The king later told the duke of Burgundy that, although they had been paid for six months, they were complaining that they had been at great expense for a variety of reasons, and were reluctant to serve much longer without a further instalment of wages, especially if they were to organize winter quarters.

These logistic arguments were reinforced by Edward’s political disappointments. Brittany had made no move. The count of St Pol, as Louis had predicted, had defaulted on his promises. There was no sign of the hoped-for rising of the French feudality. Burgundy himself had failed to carry out his part of their contract. To proceed with the agreed plan involved gambling on the duke’s good faith and his ability to deal with his enemies in distant Lorraine; but they had no means of knowing how long this might take, or whether the now almost bankrupt duke could raise an army to take the field. There seemed to be every prospect that the English might be left to fight the French alone, something which Edward had always wished to avoid. The French were numerically far superior, and the English troops were not the seasoned warriors trained in continental warfare who had been available a generation previously. No doubt these were the arguments of discretion rather than valour. Perhaps they would have held less appeal to an Edward III or a Henry V. But to Edward and most of his noble captains they were cogent reasons for making terms with the French as soon as possible. When Duke Charles – rather unwisely, considering the temper of his allies – left Péronne about 12 August to join his own men in Bar, the English lost no time in entering into negotiations with King Louis. Their first approach was a diplomatic finesse worthy of King Louis himself. They released a French prisoner, a valet in the service of one of Louis’s household gentlemen, Jacques de Gracay, and he was given a crown each by Lords Howard and Stanley and told to recommend them to the king of France. Remembering what Garter King of Arms had told him of these two noblemen, Louis interpreted the signs correctly. In reply he sent back a young valet of his household who was briefed by Commynes personally. He was instructed to tell the king of England that Louis had always wished for peace with England, and that any apparently hostile acts he had committed were, in reality, directed against the duke of Burgundy, a prince concerned only with his own interests. He was to say that Louis knew that Edward had been at great expense, and that many of his subjects in England wanted war with France. Nevertheless, if Edward would consider a treaty, then Louis could offer terms which might please both the king and his people. A meeting could be arranged, either for French envoys to visit the English camp, or half-way between the armies with delegates from both sides. After consultation with his advisers, Edward agreed.

On 13 August he drew up instructions for his delegates, John, Lord Howard, Sir Thomas St Leger, Dr John Morton, master of the rolls, and William Dudley, dean of the chapel royal, and he took care to have them witnessed by his brothers, Clarence and Gloucester, and the other leading members of his company. King Louis similarly empowered his own representatives, headed by the admiral of France, Jean, bastard of Bourbon, and the next day the two parties met in a village not far from Amiens. The English proposals were precise and practical. The king of France was to undertake to pay Edward 75,000 crowns (£15,000) within fifteen days, and 50,000 crowns (£10,000) yearly thereafter for as long as they both lived. His heir, the dauphin, was to marry Edward’s first or second daughter, and to provide her with a livelihood of £60,000 yearly in French values. If this were agreed upon, Edward would take his army back to England as soon as possible, leaving behind hostages who should be released as soon as the larger part of the army was safely home. Edward also wanted a ‘private amity’ binding himself and Louis to aid each other in case either was ‘wronged or disobeyed’ by his subjects, and a truce and an ‘intercourse of merchandise’ for seven years. Louis, anxious to come to terms before the duke of Burgundy returned, or any other dangers developed, agreed at once to the English offer, and urgent instructions were sent out to his agents to raise the sums necessary to meet the English demands and further monies intended as bribes to win the goodwill of some of the English lords. By 18 August the terms of the truce had been decided, and plans made for a meeting between the two sovereigns on the Somme near Amiens. To satisfy the pride of the English soldiers, both armies should march to the rendezvous in battle-array, before the leaders met on a convenient bridge with the river separating the two forces.

Neither the fury and contempt of Duke Charles, who returned to the English camp from Valenciennes on 19 August, nor the pleadings of St Pol, had any effect upon the resolve of Edward and his captains. Both were told, in effect, that they had forfeited all claim to consideration. Charles was also informed that he could be included in the truce with France if he gave three months’ notice, but he angrily refused the offer and withdrew to Namur. On 25 August the French and English armies both appeared near Amiens. Anxious to win the goodwill of the English rank-and-file, Louis provided food and wine in great quantities and instructed the innkeepers of Amiens to issue free drink to any English soldier who cared to ask for it. No English army is, or ever has been, proof against this temptation. For three or four days the English troops drank happily at French expense, and Amiens was full of thousands of sodden men-at-arms and archers. Eventually Edward himself was forced to eject his men from the city and post a guard at the gate.

Arrangements went ahead, meanwhile, for the meeting of the two kings. At Picquigny, three miles down-river from Amiens, where the Somme was narrow but not fordable, a bridge was built with a screen across the centre, pierced by a trellis through which conversation could be carried on: these precautions were taken to prevent any repetition of the treachery which had cost the life of John, duke of Burgundy, at a similar meeting on the bridge of Montereau in September 1419. For what followed we have the invaluable eye-witness testimony of Philippe de Commynes. Impressed by the apparent size of the English army drawn up in order (‘an incredibly large number of horsemen’), the French royal party first took up their position on the bridge, and then, says Commynes:

The king of England came along the causeway which I mentioned and was well attended. He appeared a truly regal figure. With him were his brother, the duke of Clarence, the earl of Northumberland, and several lords including his chamberlain, Lord Hastings, his Chancellor and others. There were only three or four others dressed in cloth of gold like King Edward, who wore a black velvet cap on his head decorated with a large fleur-de-lis of precious stones. He was a very good-looking, tall prince, but he was beginning to get fat and I had seen him on previous occasions looking more handsome. Indeed I do not recall ever having seen such a fine-looking man as he was when my lord of Warwick forced him to flee from England.

When he was within four or five feet of the barrier he raised his hat and bowed to within six inches of the ground. The King, who was already leaning on the barrier, returned his greeting with much politeness. They began to embrace each other through the holes and the king of England made another even deeper bow. The King began the conversation and said to him, ‘My lord, my cousin, you are very welcome. There’s nobody in the world whom I would want to meet more than you. And God be praised that we have met here for this good purpose.’

The king of England replied to this in quite good French.

After an address by the English chancellor, Bishop Rotherham, articles of the treaty were exchanged, and the two kings solemnly swore to observe them. The French king then fell to banter, and jokingly told Edward that

he ought to come to Paris, that he would dine him with the ladies and that he would give my lord the cardinal of Bourbon as confessor, since the latter would very willingly absolve him from sin if he should have committed any, because he knew the cardinal was a jolly good fellow.

The escorts then withdrew and the two monarchs conversed privately for a while. Commynes noted as evidence of Edward’s good memory that, when Louis asked Edward if he remembered Commynes, the latter said he did, and ‘mentioned the places where he had seen me and that previously I had put myself to much trouble in serving him at Calais’. The kings then discussed the position of Burgundy and Brittany, with Edward replying that he did not care what happened to Burgundy if he did not choose to keep the truce, but pleading that Brittany should be included in the truce, saying he did not want to make war on the duke of Brittany, for ‘in his moment of need he had never found such a good friend’. After further polite exchanges, the meeting broke up. Commynes records that Duke Richard of Gloucester and several others were not pleased by the peace, but became reconciled to it, and Gloucester visited Louis at Amiens, and received from him some very fine presents.