To understand this positive military context, a more realistic view has to be taken of the effects of military enterprise, which was an all‐pervasive and deliberate response of most seventeenth‐century governments to the administrative burdens and unsustainable costs of trying to set up their own armies and navies. Military enterprise in this period should not simply be dismissed as the last gasp of a terminally defective condottiere system. Colonels and senior officers had certainly invested heavily in their military forces, but this did not make them risk‐averse or reluctant to think in strategic terms. Many of the commanders were hybrids: both investors in the military system and holders of military commands granted them by their ruler, with whom they had a relationship that would determine their own and their families’ political and social status. Even as military investors, they could not afford to ignore the progress and the ultimate outcome of the war. In the case of the Swedish colonels and high command, for example, it was obvious that only a Swedish‐dictated peace settlement would provide them with the vast sums that they considered were outstanding on their financial commitment to the war effort, and which the Swedish monarchy would never be able to provide from its own resources.

However, the presence of enterpriser investors did ensure a very different attitude to the waging of war: one in which military operations were characterized by far more instrumentality in the linking of means to ends than in traditional ‘state’ warfare organized, funded, and waged directly by rulers. Instead of war as a dynastic process, part of the public assertion of the prince’s status and the defence of princely honour and reputation, military operations outsourced to enterprisers were seen as the pursuit of objectives that would heap up the pressure on an enemy, but at realistic cost and risk. Forcing a battle that could destroy some of the fighting potential of an enemy army was a means to assert this pressure, but it would be a costly and wasteful success if it was not backed up by operational capacity—the ability to keep the army in being and enabled to pursue objectives through the rest of the campaign.

The strategic significance of sustained operational capacity as the primary means to achieve military goals was recognized by a succession of capable commanders in the field. In this respect, the assertion that the logistical problems involved in supplying armies necessarily prevented operational effectiveness in the Thirty Years War is simply unconvincing. The evidence of the activities of successful commanders of Bavarian, Imperial, and Swedish armies tells a different story. If logistical support determined the ability of armies to pursue coherent operational goals, to follow up military engagements, and to exploit opportunities as they opened up throughout a campaign, then a level of success in supplying these armies must have been achieved.

How was this done? Simply to summarize the key factors, the most important was an intuitive, problem‐solving approach to maintaining the strategic capability of armies, a shaping of military means to ends. In the first part of the war, the large campaign forces of, for example, the Imperial commander and military enterpriser Albrecht Wallenstein, and of Gustavus Adolphus, did indeed suffer immense problems in amassing and providing logistical support—problems that threatened the destruction of the armies, or turned military operations either into simple territorial occupation or the cumbersome pursuit of crude, easily anticipated campaign objectives. The primary responses to the problems of keeping armies sufficiently supplied to maintain high levels of mobility and operational initiative were a systematic scaling down of the size of campaign armies and a shift in the numerical relationship between troops engaged in garrisoning and tax extraction and troops operating in the field. This was a deliberate decision, not some unintended consequence of the war as demographic disaster.

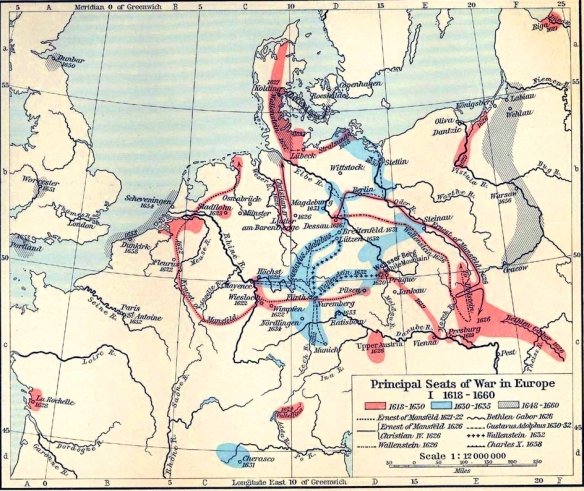

Drastic downsizing of field armies was accompanied by a change from traditional infantry predominance to higher proportions of (more expensive) cavalry. The 1631 battle of Breitenfeld had been fought between 42,000 troops led by Gustavus Adolphus against 32,000 Imperials and Bavarians; at the battle of Jankow in 1645, around 15,500 Swedish and German troops engaged with Imperial and Bavarian forces of around 16,000. The Swedish army contained 9,000 cavalry, the Imperial around 11,000.48 Mobility was being prioritized, as was the generally smaller logistical ‘footprint’ created by scaled‐down, cavalry‐dominated field armies. And while numbers of troops were reduced, their quality, indicated by the ever higher proportions of experienced veterans in their ranks, increased. These armies contained strikingly large proportions of long‐serving soldiers, resilient both in their ability to continue operating despite irregular and variable food supplies and in their epidemiological resistance, a much‐neglected factor in military effectiveness. They fought hard and ruthlessly, whether in terms of taking and inflicting casualties in battle, sustaining the rigours of campaigns that might involve force‐marching hundreds of miles, or exploiting circumstances that involved tactical flexibility, such as campaigning into the winter months, when armies were traditionally rested and reconstituted.

In ensuring a basic level of food and munitions supply, the commanders of these small armies benefited from administrative decentralization. Financial resources were usually collected by widely dispersed garrison troops who occupied specified territories and exacted war taxes, or ‘contributions’ that had been agreed with the populations as the (high) price of providing protection from predatory enemy forces and the otherwise random demands of the troops. Accepting this financial burden and garrisoning was the cost of remaining neutral, or at least not being directly involved in military activity. Just as garrisoned territories such as Mecklenburg, Pomerania, and Brandenburg provided the financial support for the main Swedish campaign army, the territories of the Westphalian Imperial Circle contributed substantially to keeping the Imperial field armies operational. The monies collected were paid directly to the commanders, who themselves negotiated with suppliers and merchants to provision the army in the light of plans for the forthcoming campaign.

These relationships, like those between the commanders and their bankers and financiers, who could be persuaded to anticipate revenues and provide loans at short notice, were direct and personalized. Direct experience left the commanders acutely aware of what could and could not be achieved in supplying the armies, and led to a careful structuring of campaigns around supply networks, especially waterways and interior lines. When Bernhard of Saxe‐Weimar, one of the most successful commanders of a ‘downsized’ army composed of colonel investors, decided to undertake the siege of Breisach on the Rhine in 1638, the key to the decision was his confidence that his financier and supply agent Marx Conrad Rehlinger would acquire sufficient grain and other provisions in the Swiss cantons against Saxe‐Weimar’s credit, and would maintain a steady shipment of these supplies down the Rhine from his base in Basel for the duration of the siege.

In fact, one of the consequences of this emphasis on small, mobile armies was a reluctance to engage in large‐scale sieges. Many of these armies had abandoned a cumbersome siege train of heavy artillery and focused on much lighter, more mobile field guns. Siege guns would need to be called up to undertake a siege, and in most cases a cost‐benefit analysis of the logistical and manpower costs would militate against this style of campaigning.51 This stood in obvious contrast to the style of traditional, directly controlled armies like those of the French and the Spanish operating on the Flanders frontier, where sieges were still explicitly identified with the status and prestige of rival monarchs and undertaken regardless of costs and the commitment of resources. The armies operating in the Holy Roman Empire were more likely to use surprise, trickery, or intimidation to try to capture a fortified town. In many cases, they simply left such places alone, focusing on what seemed more likely to bring about operational benefits: the ability to outmanoeuvre rival forces and cut deep into enemy territory, bringing the pillage and destruction associated with the chevauchées of the Hundred Years War.

It was the destructiveness of a coordinated sweep into Bavaria by the Swedish army and the French army in Germany that forced the Bavarian Elector into the ceasefire of Ulm in early 1647. Battles had their place in this type of operational thinking, but they had to be part of a wider set of campaigning goals. In 1645 the Swedish commander Lennart Torstensson determined to force a battle with the Imperial field army as early in the year as possible; if he was successful, it would leave the rest of the campaign to pile up pressure on Habsburg territory. His decisive victory at Jankow in early March 1645 was followed by a fast‐moving, hard‐hitting campaign that took his army to within one day’s march of Vienna by 6 April.

Commanders in this period did have a coherent grasp of strategy in the sense of an ability to relate military means to ends. It depended on maintaining operational capability throughout entire campaigns, and from one campaign to the next. The changing size and shape of the armies and the approach to warfare was a clear reflection of this priority. The aim, shared by commanders as diverse as Banér, Hatzfeld, Piccolomini, Mercy, and Wrangel, was to pile up incremental advantages brought by rapid mobility, territorial devastation, attrition of enemy veteran troops, and the concentration of the direct burden of supporting armies more and more on the territory of their opponents. The problem was that such an incremental approach was slow to achieve strategic results, especially when the belligerents were quite evenly matched in terms of operational capability and the capacity to frustrate the projects of an enemy.