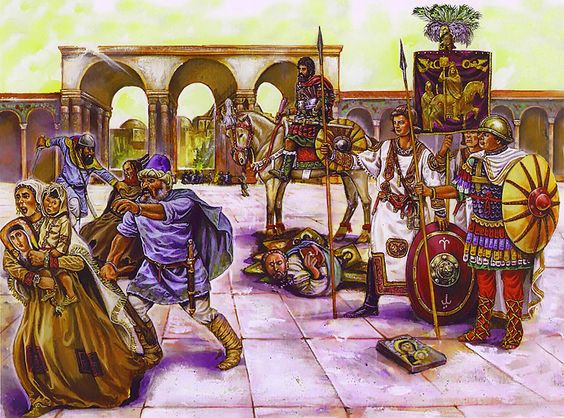

Avar and Bulgar warriors, eastern Europe, 8th century AD.

Leo III (717–741)

Leo III, like Herakleios, intervened in Byzantine politics at a decisive moment, and he set the state on a sound basis, militarily and politically. His first problem was an Arab siege of Constantinople, which began almost immediately after he seized the throne. After withstanding the siege, Leo began to carry the war to the Arab armies and he succeeded, by the end of his reign, in freeing western Asia Minor from Arab raids. In domestic matters he is best known for his codification of law, the Ekloga, and his policy of Iconoclasm. The investigation of the latter is particularly difficult because the Iconophile sources are universal in their condemnation of the emperor, and there are virtually no extant Iconclast sources.

Leo’s family had come from Syria and was settled in Thrace as part of Justinian II’s policy of population transfers. The appellation “Isaurian” for Leo and his dynasty is thus probably a misnomer. Leo had come to the attention of Justinian II when he helped the emperor regain his throne in 705, and he rose to prominence in the army. He became strategos of the Anatolikon theme under Anastasios II, and during the reign of Theodosios III Leo allied with Ardavasdos, strategos of Armeniakon, and seized the throne in 717. He found the capital in a situation of some distress after 30 years of political instability.

Because of the confusion in Constantinople since the death of Constantine IV, the Arabs had made considerable headway in Asia Minor, and the Arab general Maslama (brother of the caliphs Walid, Sulayman, and Yazid (705–24)) planned another direct attack on the capital. The siege of Constantinople began in August of 717, supported by Sulayman’s navy. Leo won a victory in Asia Minor and attacked the Arabs from the rear, while his Bulgar allies (under Tervel) attacked from the west, and Greek Fire again did its work on the Arab fleet. As a result, Maslama withdrew in August of 718 after absorbing heavy losses.

The theme system was now fully operational and it provided considerable strength in the face of continued Arab raids. Thus, when the caliph al-Malik (723–42) pushed deep into Byzantine territory, Leo won signal victories at Nicaea in 726 and Akroinon in 740 (Map 9.1), so that by the end of his reign western Asia Minor was relatively secure against Arab incursions. In part, Leo’s successes against the Arabs were the result of his alliance with the Georgians and Khazars. As we have seen, the Khazars, a semi-nomadic Turkic people who lived north of the Black Sea, could attack the Arabs from the rear, and they had been involved in Byzantine policy at least since the marriage of Justinian II to the khan’s daughter. Leo cemented his own alliance with the Khazars by marrying his son Constantine to a Khazar princess.

Just like his predecessors, Leo had to face several revolts, especially at the beginning of his reign, most of them led by theme commanders. Leo understood the problems with this system, since he had himself come to power in this way, and he responded by providing greater central control and perhaps also by dividing up several of the larger themes into smaller entities, thereby diminishing the power of any individual theme commander. This is not to say that the fear of revolts was the only reason for the division of the themes; in part it was an indication that the military situation, especially in Asia Minor, had improved from the catastrophic years of the seventh century, and that the administrative system of the themes was working well generally.

Leo was a careful administrator and an autocrat. Both of these characteristics are shown in the Ekloga, a legal codification, issued probably in 726 (or possibly 741). According to the preface of the text, God had entrusted the emperor with the promotion of justice throughout the world, and the new code was part of the emperor’s attempt to promote just that. In his view, the current codifications of law were confusing and largely incomprehensible (in part because they were contradictory and still largely in Latin). Judges and lawyers, not only (according to the Ekloga) in the provinces, but also in the “God-protected city” (Constantinople) were ignorant of what the law said. The Ekloga was a practical handbook designed for everyday use, rather than a treatise that provided a theoretical base for the law. It restricted the right of divorce and provided a long list of sexual crimes. The Ekloga also introduced a new system of punishment, including judicial mutilation, but practically did away with capital punishment.

Constantine V (741–775)

Under Leo III’s son and successor, the Isaurian dynasty reached the height of its power, and Iconoclast policy hardened into outright persecution of the Iconophiles (or Iconodoules, as they are sometimes called).

Constantine V is one of the most interesting of all Byzantine emperors. His rule was generally successful and he was intelligent and determined; yet the Iconophile sources viewed him as their greatest enemy, so his reputation has been blackened beyond that of almost any other emperor. Constantine was born in 718 and the Iconophile sources say that when he was being baptized he defecated in the baptismal font, giving rise to his nickname of Kopronymos (“Dung-name”). He was crowned as co-emperor in 720 and in 732 he was married to Irene, the daughter of the Khazar khan; after her death, he married twice.

Athough Leo III had clearly designated Constantine to succeed him, a revolt broke out immediately in 741, led by his brother-in-law Artabasdos, who apparently opposed Leo’s Iconoclasm. Artabasdos initially defeated Constantine, gained control of Constantinople, and sought to establish a dynasty of his own. Constantine, however, defeated him in 743 and regained control of the capital, blinding Artabasdos and his sons.

Once established firmly on the throne, Constantine V continued the successful military policy of his father and was able to take the offensive in Asia Minor. The Arabs were weakened by their own political problems, which led to the collapse of the Umayyad dynasty and its replacement by the Abbasid dynasty in 750. The Arab capital was moved from Damascus (in Syria) to Baghdad (in Iraq) and the Abbasids were generally less concerned with their western frontier (and warfare with Byzantium) than the Umayyads had been.

Just as the Arab threat began to abate, however, there was a new danger from Bulgaria. Constantine pursued an aggressive policy against the Bulgars and dealt them a crushing blow at the Battle of Anchialos in 763. At the same time Constantine V almost completely ignored the situation in Italy, in part because he realized that his support for Iconoclasm prevented any rapprochement with the papacy, and this led to a considerable change in the political equilibrium in Italy. Since 726 the papacy had disagreed with Byzantine policy on Iconoclasm and it now saw little difference between the “schismatic” Greeks and the Germanic Lombards who had threatened papal possessions over the past two centuries. Previously, the papacy had looked to the Byzantine emperor as a military protector, but Iconoclasm and the lack of interest of the Isaurian emperors led to the collapse of this bond and to major changes in relations between Byzantium and the papacy. In 751 Ravenna fell to the Lombards and the Exarchate of Ravenna ceased to exist. It was probably in this general context (although some scholars put the event earlier, under Leo III) that Constantine V removed southern Italy, Sicily, and the southern Balkans (including Greece) from the ecclesiastical authority of the papacy and placed it under that of the patriarch of Constantinople. Leo had already quarreled with the pope about the payment of taxes and other matters in Italy, and the religious dispute over Iconoclasm made the break final. From this time forward, these areas remained under the ecclesiastical authority of Constantinople, in the case of Italy until it fell out of Byzantine military control (the last bit in AD 1071), while Greece has, of course, remained part of the eastern Christian sphere up to the present.

Constantine V was the most ferocious of the Iconoclast emperors. He apparently believed strongly in Iconoclast doctrine and composed theological tracts himself. While Leo III seems to have supported Iconoclasm as a result of his fairly basic belief in Biblical prohibitions of “graven images,” his son was a sophisticated thinker, who had a real grasp of the philosophical and theological issues involved. As a result, an Iconoclast theology was formed, and Christological arguments came to play a dominant role in the controversy. Under Constantine V, Iconoclast theologians began to see connections with the theological disputes of the past 400 years: they argued that images, in fact, raised once again the Christological problems of the fifth century. In their view, if one accepted the veneration of ikons of Christ, one was guilty of either saying that the painting was a representation of God himself (thus merging the human and the divine elements of Christ into one) or, alternatively, maintaining that the ikon depicted Christ’s human form alone (thus separating the human and the divine elements of Christ) – neither of which was acceptable. Thus, under Constantine V, the Iconoclastic controversy, which had originally been a debate about church usage and principles of public veneration, suddenly raised again all the difficult theological issues of the past.

Constantine V summoned a church council, which he naturally packed with supporters of Iconoclasm. This met at the imperial palace of Hiera on the Asiatic shore of the Bosphoros in 754 and proclaimed Iconoclast theology as orthodox, despite the opposition of important theologians such as the former patriarch Germanos, John of Damascus, and Stephen of Mount Auxentios. Although most of the treatises written by the Iconoclasts have not survived, the decisions of the Council of Hiera are preserved, since they were read into and condemned by the later Iconophile Council of Nicaea. Armed with this decision, Constantine instituted a persecution of Iconophiles. He sought to root them out of the bureaucracy and the army, and he struck especially at the monasteries, which were the centers of ikon veneration. In his zeal, Constantine went beyond the teachings of the Council of Hiera and condemned the cult of saints and relics (except, interestingly, those of the True Cross). He is even said to have personally scraped holy pictures from the walls of churches in Constantinople. Although Constantine V was reviled by the Iconophile tradition as the worst of the persecuting Iconoclasts, he was a remarkably successful general and his memory survived among those who continued to respect his military prowess. There is also good reason to believe that Constantine was enormously popular in Constantinople itself, not least because he improved the standard of living within the city and provided its inhabitants with plentiful, inexpensive food. He died in 775 while leading his troops against the Bulgars.