A British Disaster

1916

The First World War battle of Kut-al-Amara was the greatest military disaster ever to befall the British Army. Some 25,000 were lost in the fighting and another 16,000 were taken prisoner, few of whom survived captivity.

Within three months of the start of World War I, the British occupied Basra (now in Iraq), which was the Ottoman Empire’s port at the head of the Persian Gulf. Turkey had allied itself with Germany so Britain, with its huge navy, needed to secure its oil supplies in the Middle East.

The British also sought to destabilize the Ottoman Empire, which had been in decline for centuries, and also add its eastern provinces to the British Empire. In December 1914, an Anglo-Indian force advanced forty-six miles northwards from Basra. Then in May and June of the following year they advanced another ninety miles up the River Tigris. Although the oil supplies were now secure, the lure of the fabled city of Baghdad was too strong for Major-General Sir Charles Townshend, commander of the Sixth (Poona) Division. They were just eighteen miles outside Baghdad – and 300 miles from their base in Basra – when they met a strong Turkish force at the ancient city of Ctesiphon. After a fruitless battle, the British pulled back a hundred miles to Kut-al-Amara, arriving there on 3 December.

Kut-al-Amara lies on the River Tigris at its confluence with the Shatt-al-Hai canal. It was 120 miles upstream from the British positions at Amara, and 200 miles from Basra. The town lies in a loop of the river, with a small settlement on the opposite bank, and in 1915 it was a densely-populated, filthy place. The civilian population added up to around 7,000, many of whom were evicted when Townshend’s army of 10,000 marched into the town. Aware that his men were exhausted, Townshend resolved to stop at Kut, a town of key importance if the British were to hold the region. As a market town, it had good supplies of grain and it offered his men some shelter and warmth in the freezing night temperatures.

Townshend’s decision to stop at Kut was approved by the region commander-in-chief General Sir John Nixon, but the War Office in London wanted him to continue his retreat to the south because it would be impossible to get reinforcements to him there, given the other demands on manpower at the beginning of the war. Unfortunately it was already too late. By 7 December, Townshend’s 10,000 men were under siege by a Turkish force of 10,500 and eight more Turkish divisions, recently released from Gallipoli, were massing near Baghdad.

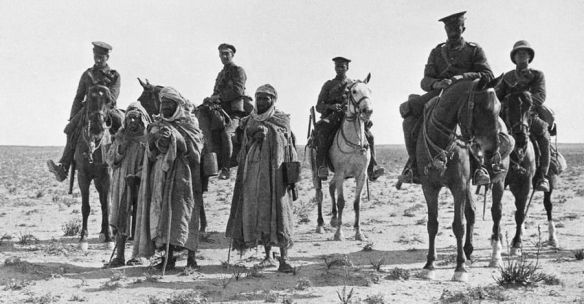

Townshend calculated that there were enough supplies in Kut to last a month. Fortunately he had evacuated the cavalry on the day before the Turks arrived because there was little forage. However, Townshend was told that it might take two months for a relief force to arrive. Even so, he kept his men on the full daily ration because he planned to break out. General Nixon, on the other hand, ordered him to remain and hold as many Turkish troops around Kut as possible.

The Turkish commander, Nur-Ud-Din, and his German counterpart, Baron von der Goltz, were given straightforward instructions. They were to drive the British out of Mesopotamia. In December they made three large-scale attacks on Townshend’s position. These were beaten off with high losses on both sides so the Turks then set about blockading the town. At the same time, Turkish forces were dispatched south to prevent any British relief columns reaching Kut.

In the following January a British expeditionary force led by Sir Fenton Aylmer set out for Basra. However, their efforts w ere repeatedly repulsed at Sheikh Sa’ad, the Wadi and Hanna, involving them in heavy losses. They met similar resistance in March, this time at Dujaila.

A second relief operation began in April under Sir George Gorringe. He managed to get far enough to meet up with Baron von der Goltz and the Turkish Sixth Army, piercing their line some twenty miles south of Kut. The expedition then ran out of steam and it was abandoned on 22 April. A final attempt to reach the town on the paddle steamer Julnar also failed, although small quantities of supplies were dropped by air. By this time, sickness in the town had reached epidemic proportions.

On 26 April 1916 Townshend was given permission to ask the Turks for a six-day armistice. They also agreed that ten days’ food could be sent to the garrison while the talks were underway. If he were allowed to withdraw, said Townshend, he would give the Turks £1 million sterling and all the guns in the town, along with a guarantee that his men would never again engage with the Ottoman Empire. Khalil Pasha, the military governor of Baghdad, wanted to accept, but the Minister of War Enver Pasha demanded unconditional surrender. He wanted a spectacular victory so that British prestige was damaged as much as possible.

During the armistice period Townshend destroyed everything that was useful in the town and on the 29 April the British garrison surrendered. It was the greatest military disaster ever to have befallen the British Army. There were 227 British officers, 204 Indian officers and 12,828 other ranks – of whom 2,592 were British. All of them were marched into captivity.

While Townshend himself was treated as an honoured guest, his undernourished men were force-marched to prison camps where they were savagely beaten, many being killed in acts of wanton cruelty. More than 3,000 men perished in captivity and those who were released two years later were little more than walking skeletons.

Approximately 2,000 British losses were sustained during the fighting at Kut-al-Amara and another 23,000 troops were lost in the attempts to relieve the trapped army. The Turks lost 10,000 men.

It was a grave error to have made a stand at Kut. Until then the British had the initiative in the fighting in Mestopotamia. The loss of Kut and the Poona Division stunned the British and their Allies and it provided a huge morale boost for both the Turks and the Germans, particularly because it came so soon after Britain’s ignominious withdrawal from Gallipoli.

Baron von der Goltz did not live to witness the triumph. He died of typhus ten days before the surrender, although there were persistent rumours that he had been poisoned by a group of young Turkish officers. Townshend was released in October 1918, in time to assist in the armistice negotiations with the Ottoman Empire.

Baghdad: The Ottoman Death Knell

The British reversed the humiliation of their surrender at Kut-al-Amara in February 1917 by retaking the town. The Anglo-Indian Mesopotamian Expeditionary Force then advanced another fifty miles up the River Tigris to al-Aziziyeh where the regional commander-in-chief Sir Frederick Stanley Maude ordered them to wait until he had received confirmation from London that a march on Baghdad was in order. Their target lay another fifty miles up the river.

This hiatus gave the regional Turkish commander-in-chief Khalil Pasha a chance to plan his defence of Baghdad. He had some 12,500 men under his command, including around 2,300 survivors from the fall of Kut-al-Amara. Two divisions of 20,000 men under Ali Ishan Bey were on their way to Baghdad across the desert from western Persia (Iran), but it was unlikely that this force would arrive in time to help in the city’s defence. Even if they did, the Turks would still only have 35,000 men at their disposal when they faced a British army of 120,000. The British would also be supported by cavalry, a flotilla of gunboats and planes for spotting and light bombing.

Khalil dismissed the option of avoiding this unequal fight by retreating from Baghdad. Simply handing the southern capital of the Ottoman Empire over to the British would be too much of a humiliation for the Turks. He also rejected the option of creating an aggressive ‘forward’ defence by abandoning work on the fortifications at Ctesiphon. For some reason, Khalil also discounted the flooding of the overland approaches to Baghdad. This would have caused Maude’s men immense difficulties and the threat of flooding remained a worry for the British even after the capture of the city.

Instead Khalil chose to defend Baghdad itself. He built defences on either side of the Tigris to the south of the city and then he deployed the Turkish Sixth Army to defend the southeast approaches to the city along the Diyala River.

After waiting for a week at al-Aziziyeh, Maude resumed his advance on 5 March 1917. Travelling up the east bank of the Tigris he reached the Diyala three days later. Small-scale crossings under the cover of darkness on the following evening resulted in the successful establishment of a small bridgehead on the north bank. Taking the bulk of the forces across the well-defended river proved to be less easy. Instead, Maude built pontoon bridges several miles downstream and moved the main body of his forces to a position from where they could cross to the west bank of the Tigris. His aim was to outflank Khalil’s defences along the Diyala and move directly on to Baghdad.

However, the German Army Air Service had just brought planes into the area. They spotted what the British were attempting to do and informed Khalil, who then moved the bulk of his forces across the Tigris, so that he would be able to counter a British attack from the southwest. He left just one regiment on the Diyala which the British overrran on the morning of 10 March. Khalil was effectively outmanoeuvred.

Khalil’s next priority was to guard his rear so he moved his forces to the west of their position in Tel Aswad. Their task was to protect the railway that started from Baghdad and ran all the way back to the heart of the Ottoman Empire and on to Berlin. The battle for Baghdad was then halted by a sand-storm. The Germans urged Khalil to stage a counterattack but by the time the weather had cleared he had decided to pull out of the city. At eight p.m. on 10 March the retreat from Baghdad was under way.

On the following day Maude’s troops entered the city without a struggle. Baghdad’s 140,000 occupants lined the streets, cheering and clapping. For the last two years the Turkish Army had been requisitioning private merchandise and shipping it out of the city. General Maude issued a proclamation that read:

People of Baghdad, remember for twenty-six generations you have suffered strange tyrants who have ever endeavoured to set one Arab house against another in order that they might profit by your dissensions. This policy is abhorrent to Great Britain and her allies for there can be neither peace nor prosperity where there is enmity or misgovernment. Our armies do not come to your cities and lands as conquerors or enemies, but as liberators.

However, Iraq did not gain its independence. The League of Nations gave Britain a mandate to run Iraq as well as Palestine, Trans-Jordan and Egypt. There was an uprising in 1920, so the British installed Lawrence of Arabia’s friend Prince Faisal as king. He promised to safeguard British oil interests in Iraq, for which Britain paid him £800,000 a month.

Some 9,000 Turkish prisoners were taken at the fall of Baghdad. Britain had sustained 40,000 casualties over the entire campaign, many having died from disease. Maude himself contracted cholera after drinking contaminated milk. He died on 18 November 1917 and was buried just outside the city walls of Baghdad.

The capture of Baghdad was a decisive propaganda blow for the Western Allies and it ended Turkish activity in Persia. Meanwhile Maude’s force moved on rapidly to capture the strategically vital railway at Samarrah.