Minorca

The Battle of Malaga by Isaac Sailmaker.1704.

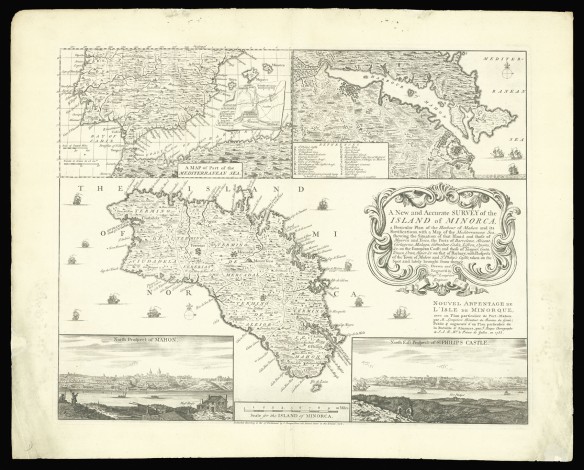

Shovell’s death was not the only loss to the allies in 1707, for in Spain Galway had been unable to maintain his hold on Madrid, and in April he was heavily defeated by Berwick at the battle of Almanza. Much of the allied position in Spain unravelled, so the need of a fleet – and therefore a fleet base – in the Mediterranean was as great as ever. The allied fleet, now commanded by Leake, arrived in May, and was soon active in supplying the allied army in Catalonia from Italy. In August Leake secured the surrender of Sardinia (part of the Spanish Mediterranean empire) to ‘Charles III’, providing an essential granary for Catalonia, and a usable naval base at Cagliari. There was, however, a much better and nearer one, which Marlborough and the queen’s ministers had been thinking about for some time: Mahón, in Minorca, by far the best harbour in the Western Mediterranean, and only 300 miles from Toulon. Leake arrived from Sardinia on 25 August and landed his marines. Soon afterwards Major-General James Stanhope arrived from Barcelona with troops, and in spite of the great strength of the island’s main fortress, St Philip’s, the conquest was completed in less than a month. Though it was made in the name of ‘Charles III’, the English intended from the beginning to keep the island for themselves.

The capture of Mahon secured the allies’ naval hold on the Western Mediterranean, but too late to affect the course of the war. The French fleet was past intervention, and the naval contribution to the war in Spain was mainly to control the export of grain from North Africa, which was supplied to the allied army in Catalonia and denied to the French. This was the main work of Sir George Byng in 1709, Sir John Norris next year, and Sir John Jennings in 1711, though Norris also attempted some raids on the coast of France.

All the while that the Mediterranean dominated allied naval strategy, war at sea in English waters had largely been confined to the defence of trade. Then the 1707 Act of Union between England and Scotland inspired another French attempt to exploit Jacobite sentiment. It seemed a good moment to advance the cause of James VIII, with few troops in Scotland, and many people less than fully committed to the Union or to Queen Anne’s government. Captain Thomas Gordon of the Scottish frigate Royal Mary, for example, was zealous in protecting Scottish merchantmen, but enjoyed a comfortable relationship with the Jacobite leader Lady Errol, who sent him a private signal to steer clear of Slains Castle whenever she had visitors from France.

The French plan was for the royal squadron from Dunkirk under the comte de Forbin to sail in midwinter and land James in the Firth of Forth before allied squadrons could intervene. Dunkirk was all but impossible to blockade effectively even in summertime, Forbin was a bold and experienced commander, and the plan seemed to have a good chance of success even after the secret leaked out and the blockade was reinforced. At first all went well. Forbin got clean away on 9 March, with Sir George Byng in pursuit but far astern. Unfortunately Forbin seems to have had no idea of the strategic value of the expedition, and to have treated it with a carelessness verging on frivolity. He made his initial landfall at dawn on the 12th fifty miles too far north, past Stonehaven; a disastrous blunder which has never been explained. It was the evening of the 13th before the French were able to enter the Forth and anchor off Anstruther. Byng anchored near by off May Island later that night, unseen in the darkness. Even then there was time to land James and his troops, and the sacrifice of Forbin’s small squadron would have been well worth it, but when he sighted Byng’s squadron at dawn, he insisted on escaping to the northward. In the ensuing chase one French ship, the Salisbury (an English prize taken in 1703) was captured by her British namesake (built 1707), but the rest escaped, and Forbin refused another chance to land James. Thus the French threw away a good chance to create, at least, an effective diversion to Marlborough’s plans, which after his victory at Oudenarde on 30 June/11 July, developed into an invasion of France.

The naval war in the Caribbean revived in 1705. In April the enterprising Canadian Iberville mounted a destructive raid on Nevis, only to die of yellow fever at Havana on his way to attack Carolina. In May Rear-Admiral Whetstone arrived with an English squadron, reinforced in August by Commodore William Kerr, who later succeeded to the command. Kerr’s squadron was immobilized by sickness and almost starved; he received no victuals from England until July 1707, and could do nothing to intercept the French squadron which du Casse had brought out to collect Spanish silver. Sir John Jennings arrived in December 1706, with the primary mission of persuading the Spanish governors to acknowledge the authority of ‘Charles III’. In this he failed completely, and returned to England in May 1708, shortly followed by Kerr, who only got back by dint of borrowing men from the incoming British squadron. Kerr was then prosecuted in the common law courts, impeached by the House of Lords and dismissed from the Service for neglecting trade and demanding convoy fees.

Kerr’s relief was Commodore Charles Wager, who sailed in April 1707 with a squadron of seven ships of the line. He was followed by du Casse, who sailed from Brest in October, but spent only a short time in the Caribbean, leaving Havana in July 1708 with the Spanish silver from Mexico – but not the South American silver shipped from Porto Bello, which Wager had intercepted on 28 May. Like Benbow, Wager was abandoned by two of his captains, but he pressed home his attack with his own ship unsupported, took one and sank another of the Spanish ships. The Spaniards lost much money, and a good deal of what du Casse took home never reached Spanish hands. Wager returned to England in December 1709, but the British squadron remained on station.

Further north there was desultory action on the Anglo-Spanish frontier throughout this war, with mutual raids from Carolina and Florida. The English twice attacked the Spanish port of Pensacola, and in 1706 a force of Spanish and French privateers raided Charleston. In these waters, moreover, especially North Carolina (‘where there’s scarce any form of government’, as the Governor of Virginia alleged), piracy was still a real problem. Massachusetts expeditions reached the French privateer base of Port Royal, Acadia, in June and August 1707, but were unable to make an impression on the French defences. On 1 October 1710 the Americans finally achieved a success in taking Port Royal (renamed Annapolis Royal), ‘seven years the great pest and trouble of all navigation and trade of your Majesty’s provinces on the coast of America’.

In European waters another distraction was caused by the Great Northern War between the Baltic powers, which broke out in 1702. The belligerents of the Spanish Succession war were not directly involved, but all European navies depended more or less on mast timber and naval stores imported from the Baltic, while Baltic grain exports became progressively more essential both to England and France in the years of dearth from 1708. The Dutch moreover provided almost all the shipping which carried these goods. The Maritime Powers therefore needed to cover their shipping from Swedish and Russian attacks, while in the North Sea there were both French and allied grain convoys to be attacked and defended. In the Baltic the Swedes were the main aggressors, and relations with England were not helped by the old irritant of the ‘salute to the flag’, which provoked a bloody action off Orfordness in July 1704 between Whetstone and the Swedish Captain Gustav von Psilander of the Öland. In 1709 Norris took a squadron as far as the Sound to escort allied trade and intercept French. From 1710 Swedish privateers became more troublesome, but as long as the war against Spain lasted, the allies had no ships to spare to protect their trade within the Baltic.

Inevitably, it was French privateers that presented the main threat to allied trade. The French continued the composite trade war which had been so effective in the previous war, with squadrons of royal warships, either equipped by the crown or chartered to private shipowners, used as the nutcrackers to break open convoy defences and expose the riches within. The commanders of these squadrons were the heroes of the French war on trade. In May 1703 the marquis de Coëtlogon intercepted a Dutch convoy under Captain Roemer Vlacq off Lisbon and sank or captured all five escorts: a notable victory, but a sterile one, for the escort’s sacrifice enabled the entire convoy of over 100 sail to escape. Unfortunately for the French this was too often the pattern. The chevalier de Saint Pol de Hécourt, commanding the Dunkirk squadron, in 1703 took the Ludlow, 34 (i.e. of thirty-four guns), and later the Salisbury, 52, which he took for his own command. He also inflicted heavy losses on the Dutch fishing fleet off Shetland. Next year he took another English ship of the line, the Falmouth, 58. ‘It is to be desired,’ commented a French official, ‘that Monsieur de Saint Pol find fewer men-of-war and rather more Indiamen or rich interlopers, which would suit his poor owners much better.’ Instead he took a Dutch fifty-gun ship, the Wulverhorst, but once again the convoy had escaped by the time the escort was overwhelmed. Saint Pol’s accounts for this loss-making cruise still had not been cleared up in 1718. In the same year 1704, Duguay-Trouin from St Malo took the Coventry, 54, and the Elizabeth, 70. Both English captains were sent to prison, one of them for life. Finally in October 1705 Saint Pol took an English convoy complete, three escorts and eighteen merchantmen, but was killed in the attack.

His successor in command of the Dunkirk squadron was Forbin, a Gascon nobleman with many of the qualities traditionally associated with his country: bold, gallant and skilful; but also vainglorious and grasping. In May 1707 his squadron of eight ships of the line took two seventy-gun ships, the Hampton Court and Grafton with twenty-two ships of their convoy off Beachy Head, though more than half the merchantmen escaped. In the summer Forbin went north into the Arctic. Whetstone formed the escort of an allied convoy to Archangel, which he had left north of the Shetlands (further north than his orders required), before returning to other duties. Forbin intercepted the convoy off the Murman coast of Arctic Russia, but the local escort under Captain Richard Haddock saved it in a fog bank, and Forbin got only some stragglers. Then on 10 October off Ushant, the squadrons of Forbin and Duguay-Trouin by chance together encountered a convoy carrying troops to Lisbon. Between them they had twelve ships of the line against the five of the escort, though Captain John Richards had two three-deckers, the Devonshire, 90, and the Cumberland, 82. Duguay-Trouin did most of the fighting, in which the Devonshire was burned and three more escorts taken. Forbin arrived later and went straight for the convoy, taking ten (out of about 100). He made all the money, and with undamaged ships he returned early to port to claim all the credit.

Against the undoubted successes of French squadrons must be set the many convoys which were successfully defended, or never attacked at all, and even the most celebrated French commanders were not always successful. In 1704 Saint Pol with six warships was frightened off a Virginia convoy of 135 sail under Captain John Evans, who formed a line of battle with his own four escorts and the ten biggest merchantmen. In 1706 Duguay-Trouin intercepted a rich Portuguese Brazil convoy off Lisbon; one escort was taken, but the Portuguese warships saved the whole convoy. His greatest exploit was the sack of Rio de Janeiro in 1711, which did return a profit, but overall Duguay-Trouin’s career cost his investors and himself a great deal of money. His home port, St Malo, prospered in this war because it progressively abandoned privateering in favour of the extremely profitable interloping trade round Cape Horn to the ‘South Sea’, the Pacific coast of Spanish South America. Three ships which returned from Peru in May 1705 declared cargoes worth more than half the entire gross earnings of all the privateers of the port between 1702 and 1713. In 1709 a convoy of seven ships escorted by Captain Michel Chabert came home laden with Spanish silver, of which Louis XIV received over four million pesos, and a quarter of a million found its way back to Philip V.

The French privateering war certainly caused England heavy losses – the contemporary claim of 3,600 merchantmen taken during the war was probably not much exaggerated – but it is not at all clear that it was profitable, either economically or militarily. English foreign trade was more buoyant than in the 1690s, and better able to bear losses. With experience, the organization of trade protection became gradually more effective, and imaginative. In 1709, in response to petitions from the Scottish Burghs, the local escorts on the east coast of Scotland were put under the operational command of the Lord Provost of Edinburgh, who for the rest of the war controlled the convoy system between Newcastle and the Orkneys and across the North Sea. Moreover the efforts of allied privateers, especially from Zealand and the Channel Isles, have to be taken into account.

As in the previous war, the French naval strategy was most effective in English politics. The heavy losses of 1707 caused an outcry in Parliament: ‘Your disasters at sea have been so many, that a man scarce knows where to begin,’ declaimed Lord Haversham in the House of Lords.

Your ships have been taken by your enemies as the Dutch take your herrings, by shoals, upon your own coasts; nay, your Royal Navy itself has not escaped. And these are pregnant misfortunes, and big with innumerable mischiefs; your merchants are beggared, your commerce is broke, your trade is gone, your people and manufactures ruined…

The result was the 1708 Cruizers and Convoys Act, which removed forty-three ships (nearly half of those between the Third and Sixth Rates) from Admiralty control and assigned them to specified home stations. As with the 1694 Act, the effect was probably to reduce the force available for convoy escorts in favour of cruising squadrons of doubtful effectiveness. Effectiveness, however, was not the main issue in Parliament, where Whig opponents of the government aimed to exploit back-bench disquiet to mount a coup against the Admiralty, and indirectly against Marlborough, whose brother Admiral George Churchill was blamed for mismanaging the naval war.

In this case the Whigs profited from the situation, but overall the French war on trade acted in favour of Tory opponents of the Continental war, especially Marlborough’s costly campaigns in Flanders. To aggrandize him, they argued, country gentlemen like themselves paid a heavy burden in Land Tax, too little of which went to protect England’s true interests (notably in seaborne trade), and too much of which ended up in the pockets of City financiers, who profited from the war and paid nothing towards it. Most of the financiers were Whigs in politics, Jews or Nonconformists in religion, and French, Dutch or Portuguese in origin. Associated with them were England’s Dutch allies, who were accused of bleeding England white in their defence, while they withdrew their stipulated quotas from the allied fleets and kept their own ships to escort their own convoys (frequently trading with the enemy). All the xenophobia so deeply rooted in English politics aroused MPs to demand a patriotic, profitable and English war at sea, of the sort which (as they believed) had never failed before. At the same time Tory attachment to the campaigns in Spain was fading, not only because the campaigns themselves were going very badly, but because the Archduke Charles unexpectedly succeeded to the Austrian throne on his elder brother’s death in April 1711, and a re-creation of the sixteenth-century Habsburg empire under Charles VI seemed even less palatable than the Franco-Spanish connection under Philip V.

The Tory government which took power in 1710 gave expression to these discontents. Subsequent historians have constructed a strategic tradition, the ‘Blue-Water policy’, to which the Tories were supposedly attached, but much of this is a modern rationalization of what had more to do with atavistic prejudice than rational calculation, and was to a large extent common ground among politicians of all parties. Mutual self-interest put the Whigs in bed with William III and later Marlborough, but they were not natural friends of kings and captains-general, nor of large armies and campaigns on the Continent; they were simply more realistic, or more prepared to compromise their principles for the sake of power. All English politicians were committed to the myths of English sea power, according to which a truly naval war, against a Catholic enemy, could not fail to succeed. The real distinction tended to be between those in opposition, who were wholeheartedly committed, and those in power, who were forced into some compromises with reality.

Of the leaders of the 1710 Tory administration, Robert Harley was more level-headed than his colleague St John. In March 1711 Harley was stabbed (by a captured French spy who was being questioned by a Privy Council committee), and while he was recovering, St John was largely responsible for mounting a grand amphibious expedition against Quebec. This was a response to New England requests, but it was even more an expression of Tory ideology. The troops were taken from Marlborough’s army in Flanders, and the ships were commanded by an impeccably Tory officer, Rear-Admiral Sir Hovenden Walker. To keep the expedition secret and avoid the ‘tedious forms of our marine management’, as he put it, St John kept both the Admiralty and the Navy Board in the dark, allowing some of the ships to sail with only three months’ victuals aboard in the expectation that they could be resupplied at Boston. When the expedition did arrive there at the end of June, with only a few days’ warning, Walker was surprised to find that it was difficult to supply a force of over 12,000 men (greater than the population of Boston and its surrounding district) with provisions for a whole winter. Eventually they sailed at the end of July with three months’ victuals, effectively gambling that they could conquer Quebec and find it full of food. Walker was worried about this, and further unnerved by the dangers of the St Lawrence without adequate charts or pilots – with reason, for on 23 August the fleet ran on the coast in the dark and seven transports were lost. On paper the force was still formidable, but Walker and his captains had had enough, and hastened to abandon the expedition.

By the time it returned in October, the Tory government was in the process of withdrawing from the war. One month later Marlborough was dismissed from all his offices. At the same time the ministry published Swift’s pamphlet The Conduct of the Allies, an official attack on the Dutch. ‘No nation,’ he proclaimed, ‘was ever so long or so scandalously abused by the folly, the temerity, the corruption, the ambition of its domestic enemies; or treated with so much insolence, injustice and ingratitude by its foreign friends.’ Another pamphleteer ingeniously estimated that the Dutch had made a profit from the war of £12,235,847 5s 5d.60 All this of course was meant to justify the British in abandoning their allies and withdrawing from the war. At the Treaty of Utrecht in 1713, Britain gained Gibraltar, Minorca, Acadia (renamed Nova Scotia), the whole of Newfoundland and St Kitt’s (hitherto divided), and undisputed possession of Hudson’s Bay. The Spanish Netherlands were transferred to Austria, and as Britain’s reward for betraying her allies, the French repudiated ‘James III’ and agreed to demolish the port and fortifications of Dunkirk. The reputation of ‘perfidious Albion’ was now well established in Europe, and as if to confirm it, Harley skilfully double-crossed the Jacobites, who provided a large part of his support, and engineered the peaceful succession of the Elector of Hanover when Queen Anne died on 1 August 1714.

On most reckonings the material profit to England of almost twenty-five years of costly war against France was meagre. A small number, of territories had been gained, two of them (Minorca and Gibraltar) of real, or at least potential, strategic value. The ambitions of Louis XIV had been checked, and Flanders (always so sensitive for England) safely confided to friendly hands. A Catholic dynasty had been removed, comforting English and Scottish Protestants at the price of a permanent threat to their security. Nothing so effectively destabilized a government as a legitimate pretender to the throne with support at home and abroad, so the price of Protestant liberty was eternal vigilance, and eternal expense. Less obvious than any of these changes, but in the long run most important of all, was the very rapid growth during these years of English foreign trade. The English domestic economy still depended overwhelmingly on agriculture and woollen cloth, but English (and now Scottish) merchants imported, and in large measure re-exported to Europe, greater and greater quantities of sugar and tobacco from the West Indian and American colonies, cotton from India and silk from China. These were long-distance ‘rich trades’, earning large profits but requiring large capital and advanced skills in banking, insurance and the management of shipping. Other shipowners traded in bulk goods with European ports: English cloth, timber and naval stores from the Baltic, salted cod from Newfoundland. All these trades, multiplied by the Navigation Acts, generated shipping and seamen as well as income. They went to build up what has been called a ‘maritime-imperial’ system, based on shipping and overseas trade much more than on extent of territory. Eighteenth-century Englishmen were ‘proud of their empire in the sea’; for them the word ‘empire’ still had the value of the Latin imperium, an abstract noun rather than a geographical expression. ‘Trade,’ as Addison put it, ‘without enlarging the British territories, has given us a kind of additional empire.’ To a greater and greater extent, Britain’s real wealth was generated, and seen to be generated, from a maritime system in which overseas trade created the income which paid for the Navy, merchant shipping trained the seamen which manned it, so that the Navy in turn could protect trade and the country. Much was still to be learned about how best to do both, but few informed observers in 1714 would have disputed Lord Haversham’s judgement that ‘Your trade is the mother and nurse of your seamen; your seamen are the life of your fleet; and your fleet is the security and protection of your trade: and both together are the wealth, strength, security and glory of Britain.’