The rise of Slobodan Milosevic, the man who was to become Serbian president, was sealed by an apparently impromptu speech he gave in Kosovo Polje on 24 April 1987. The leader of the League of Communists of Serbia emerged from a meeting of angry Kosovo Serbs who were complaining of harassment at the hands of the local ethnic Albanian-dominated authorities:

First I want to tell you, comrades, that you should stay here. This is your country, these are your houses, your fields and gardens, your memories. You are not going to abandon your lands because life is hard, because you are oppressed by injustice and humiliation. It has never been a characteristic of the Serbian and Montenegrin people to retreat in the face of obstacles, to demobilise when they should fight, to become demoralised when things are difficult. You should stay here, both for your ancestors and your descendants. Otherwise you would shame your ancestors and disappoint your descendants. But I do not suggest you stay here suffering and enduring a situation with which you are not satisfied. On the contrary! It should be changed, together with all progressive people here, in Serbia and in Yugoslavia. . . . Yugoslavia does not exist without Kosovo! Yugoslavia would disintegrate without Kosovo! Yugoslavia and Serbia are not going to give up Kosovo!

Soon after 1389 the Serbian Patriarch Danilo recorded what he claimed was a speech given by Prince Lazar to his men on the eve of combat:

You, oh comrades and brothers, lords and nobles, soldiers and vojvodas [dukes] great and small. You yourselves are witnesses and observers of that great goodness God has given us in this life. . . . But if the sword, if wounds, or if the darkness of death comes to us, we accept them sweetly for Christ and for the godliness of our homeland. It is better to die in battle than to live in shame. Better it is for us to accept death from the sword in battle than to offer our shoulders to the enemy. We have lived a long time for the world; in the end we seek to accept the martyr’s struggle and to live forever in heaven. We call ourselves Christian soldiers, martyrs for godliness to be recorded in the book of life. We do not spare our bodies in fighting in order that we may accept the holy wreaths from that One who judges all accomplishments. Sufferings beget glory and labors lead to peace.

In all of European history it is impossible to find any comparison with the effect of Kosovo on the Serbian national psyche. The battle changed the course of Serbian history, but its immediate strategic impact was far less than many subsequently came to believe. Its real, lasting legacy lay in the myths and legends which came to be woven around it, enabling it to shape the nation’s historical and national consciousness. This came about through a particular set of historical and political circumstances in the decades following the battle. A legend was created around the character of Lazar, primarily by monks, which was later preserved through the tradition of cycles of epic folk poetry. These provided a link to past glory and more importantly an inspiration for the Serbs in the nineteenth century and during the Balkan Wars when the time was ripe to shrug off Ottoman domination.

In the late 1980s, with Milosevic acting as cup-bearer, the Serbs were again to drink from the Kosovo chalice and, fortified by its heady brew of nationalism, they marched confidently into war and disaster. The irony is that Milosevic had predicted that ‘Yugoslavia would disintegrate without Kosovo’, yet it was Yugoslavia’s fate to disintegrate with Kosovo, as the fissures that spread from the unhappy province managed to splinter the rest of the country. That did not mean of course that Kosovo, with its majority ethnic Albanian population, would be happy to stay in Milosevic’s Yugoslavia. Far from it. By the end of the twentieth century what remained of Yugoslavia, then just Serbia and Montenegro, would face utter catastrophe as the conflict that began in Kosovo eventually exploded into war.

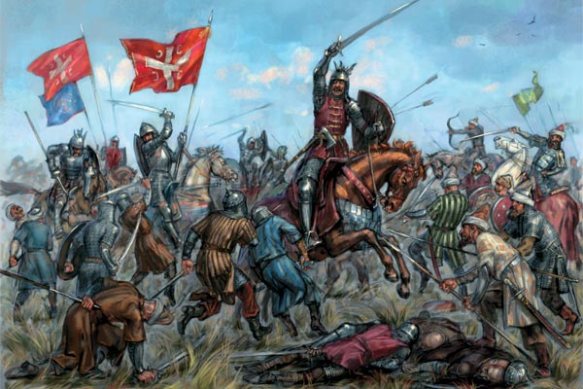

The Battle and Its Aftermath

Because it has become so central to the Serbian story, Kosovo can rightly be described as its historical crossroads. But for the Turks in the late 1380s it had no such metaphysical connotations. It was simply the next domino in their conquest of the Balkans. Much of it lay under the control of the powerful local lord Vuk Brankovic. Its plains were rich and fertile and its mines gave forth an abundance of minerals, especially gold and silver.

After the Battle on the Maritsa in 1371 the Turks spent time consolidating their rule in Bulgaria and Macedonia. By the mid-1380s, however, they began to raid Serbia itself. It was clear to all that a decisive battle was coming, especially if the Serbian lords did not submit and agree to become vassals beforehand. In 1389 Sultan Murad, acknowledging the importance of the coming conflict, not only led his troops personally but came to Kosovo with his two sons, Bayezid and Yakub. On the Serbian side the main contingents were led by Lazar and Vuk Brankovic. King Tvrtko of Bosnia had sent men under the command of Vlatko Vukovic. There were most probably also some Albanian contingents under Lazar’s flag plus mercenaries from many parts of the region, as there were in the Turkish ranks too.

Considering the vast repercussions of the battle it is striking how little hard information there is about what actually happened. Later myth-makers and hagiographers were to compose histories crammed with a wealth of detail, such as Danilo’s account of Lazar’s eve-of-battle speech, but very little of this has any grounding in fact. All we know for sure is that Lazar and Sultan Murad died, along with many others. Vuk Brankovic, Vlatko Vukovic and Bayezid survived, and immediately after the battle the Turks retreated to Edirne (Adrianople), their capital at that time. Today Kosovo is written and talked about as the great Serbian defeat, the end of empire and the beginning of centuries of Ottoman bondage. Yet none of this is strictly true. First, many of the initial reports from Kosovo, far from lamenting a great Christian catastrophe, celebrated a triumph over the Turks. Secondly, as we have seen, the Serbian Empire had begun to collapse as far back as 1355 after the death of Dusan. Thirdly, after the battle, a form of Serbian state, the so-called despotate, survived, on and off, for another seventy years. Despite the constant threat from the Turks, the despotate was to see a Serbian cultural renaissance, the most important monuments of which are the monasteries of the Morava valley.

The very first record of the battle that has come down to us was made by a Russian monk who was on Turkish territory at the time, close to Constantinople. Writing twelve days after the battle he noted the death of the sultan but said nothing of victory or defeat. By contrast King Tvrtko in Bosnia was soon trumpeting his victory. On 1 August 1389 he wrote to the senate of the Dalmatian town of Trogir informing them of the sultan’s defeat. He then wrote to the Florentine senate. This letter has not been preserved, but their reply has been. In it he is congratulated on the victory and, significantly, reference is made to twelve men ‘who broke through the enemy ranks and the camels tethered round about, opening a way with their swords, and reached Murad’s tent.

‘Blessed above the rest was he who, running his sword into the throat and skirt of the leader of such a great power, heroically killed him.’

At the time the question of who had killed the sultan did not seem very important, but in later chronicles the man was named. He was Milos Obilic, or in earlier writings Kobilic. No historian can say with absolute certainty whether Obilic was an historical character, but his name came to loom ever larger, not only in Serbian epic poems about the battle but also in the national pantheon of heroes.

Gradually reports of the battle began to filter across Europe but they were either unspecific about its outcome or they talked of a Christian victory. As in Chinese Whispers these reports also tended to become ever more distorted in the telling. By the time they reached Paris, for example, the French chronicler Philippe Mesière recorded that the sultan ‘had been completely defeated. . . . Both he and his sons fell in the battle as well as the bravest of their army.’ These reports did not talk much about the death of Prince Lazar, who, at least in the west, was an obscure Balkan princeling.

A wealth of modern scholarship has examined scores of chronicles, Serbian, Turkish and others, written in the decades after the battle. What appears to have happened is that both sides, reeling from the loss of their leaders, now needed to consolidate power in the hands of their successors. On the Turkish side this was swift and bloody. After Murad’s death Bayezid summoned his younger brother Yakub, murdered him and then hurried home to Edirne to secure his succession.

On the Serbian side it was the consolidation of power in the hands of Lazar’s clan which gave birth to the myth of Kosovo. Lazar’s widow Milica needed to secure the succession of their son Stefan, who in 1389 was still a young boy. Apart from retaining power, she had other urgent matters to attend to. Although it was not immediately evident that Kosovo was a military defeat, its implications were soon becoming clear, While Lazar’s Serbia had been relatively wealthy and strong, it was no long-term match for the far more powerful Ottomans. If both armies had suffered heavy losses, only the Turks had a plentiful supply of fresh manpower to call upon when they returned home. No sooner had Bayezid secured his succession than the Turks were back demanding that Milica submit to his authority. With the Hungarians threatening the north, there was little choice. What had been Lazar’s Serbia became a vassal state. Stefan and his brother Vuk were not yet old enough to lead troops for Bayezid, but tribute had to be paid including the despatch of Lazar’s fourteen-year-old daughter Olivera to grace Bayezid’s harem.

In a bid to shore up her power-base against the potential threat of the other marauding Serbian lords who might now want to partition her lands, Milica put church scribes to work to sanctify Lazar in order to bolster Stefan’s claim on power. So, as the scribes eulogised his ‘saintly’ father, young Stefan, like the Nemanjas, could also claim to be a ‘sapling’ from a ‘holy root’. It would be too cynical to suggest that securing the position of young Stefan was the only reason for the canonisation of Lazar, but it was certainly a powerful motivation. In medieval society the church was the main source of news and information for ordinary people. As Lazar had been favoured by the church above the other Serbian lords of the time, its priests were happy to play their part.

Within a few years of the battle Stefan Lazarevic was old enough to fulfil his obligations as a vassal most importantly he was required to come to the Sultan’s aid along with his soldiers. This led to a curious situation, but one which was then accepted as fate. While Lazar himself was being venerated as a saint and as the man who had given his life to save the Serbs from Murad’s Turks, his son was now fighting for Murad’s son Bayezid, who was also his brother-in-law.

Immediately after the battle, Bayezid had successfully consolidated his power, and there were ever fewer Balkan Slav leaders left who had not yet submitted to his authority. In 1396, however, the Turks had to confront the last serious crusade against them, but, in part thanks to Stefan’s intervention, the Christians were defeated. In 1402, though, Bayezid’s luck turned. This time the threat came from the east. Bayezid’s army suffered a crushing defeat at Angora (Ankara) at the hands of Timur (Tamerlane), the Mongol leader who had begun to build up his empire in far-off Samarkand. Bayezid was captured and was said to have been carried around in a cage until he died. Timur’s incursion into Asia Minor did not last long and his power crumbled after his death in 1405. However, the damage he wrought on the Ottomans was considerable and the episode managed to give a respite to the rump Byzantine Empire still lingering on in Constantinople. Stefan Lazarevic, who had fought at Ankara with Bayezid, now seized his chance to slip the Ottoman leash. Escaping from the battlefield, where his men had defeated a Tartar unit, he collected his sister Olivera from Bayezid’s harem and paid a visit to the emperor in Constantinople, Manuel II Palaeologus. He conferred on Stefan the title despot or ruler, which in Byzantine terminology does not have the negative connotations that it has in English.

Following the demise of Bayezid, his sons plunged into a bloody civil war in a bid to secure the succession. By 1413 it was over and Despot Stefan once again had to submit to Ottoman suzerainty. His nephew and successor Djuradj Brankovic (1427-56) tried to organise resistance with other Christian powers but, as usual, their own short-term interests came first. In 1427 the Hungarians made a deal with the Turks by which Djuradj Brankovic would be recognised as despot of a semi-independent buffer state which was to lie between them. It was not to last. The Turks occupied Serbia briefly in 1439 and again finally in 1459 when Smederevo, the purpose-built Danube fortress town and capital of the despotate, fell. On the map, Serbia as anything else but a far-flung Ottoman province ceased to exist. In the minds of the Serbs, however, Serbia was simply awaiting its resurrection.