The Battle of Baliqao was the culmination of the Second Opium War. An Anglo-French force of 4000 men soundly defeated a Qing Army of 30,000 east of Beijing. The allied victory was followed by the sacking of the Imperial Summer Palace northwest of the city, and the conclusion of the conflict. Prince Seng-ko-lin-Chin, one of the most successful Qing generals and Prince Sengbao, brother of the Emperor, blocked the road to Beijing with troops drawn from the Green Standard Army, reinforced by Imperial Guard troops of the Banner Army. Outnumbered and outgunned, the Anglo- French force led by French General Cousin de Montauban and British General Sir John Hope Grant attacked the Qing positions at the front and flank. After hard fighting the Qing cavalry was repulsed. The Imperial Guard held the bridge at Baliqao, but French artillery, and a determined bayonet charge by experienced infantry, dislodged them with heavy losses for the Chinese.

The Anglo-French expeditionary force landed and seized the forts at Tangku, then advanced up the Peiho River to Beijing. The combined Anglo- French force fought two successful engagements against overwhelming Qing forces, ultimately defeating them at Baliqao.

The victory at Chang chi wan over vastly superior forces gave Grant and Montauban even greater confidence in reaching the capital. As the Allies were en route to Toung-chou, the 101st Regiment under General Jamin arrived, further increasing French strength. After spending the night encamped outside the walled town, Grant and Montauban followed a canal tributary of the Peiho towards Baliqiao and its stone bridge, which carried the metalled road to the imperial capital. On the morning of 21 September, as the British and French columns moved out of their encampments past Toungchou, they found Prince Seng-ko-lin-ch’in’s army, reinforced by Imperial Guard soldiers under General Prince Sengbaou, brother of the emperor. Some 30,000 strong, it stood in position before Baliqiao Bridge.

The Chinese position was formidable, with its left on the canal, reinforced by the village of Baliqiao, another village in the centre, and a third on the far right. The road to Beijing passed through the rolling and wooded terrain and veered towards the canal and its stone bridge. Seng-ko-linch’in had brought order to his routed army, and strengthened its resolve with several thousand troops from Beijing. The prince’s position was supported by more than 100 guns in the villages, across the canal defending the bridge, and along the entire front. His army included a division of Banner soldiers, but the majority were drawn from the Green Standard Army and assorted cavalry. The Imperial Guard were kept in reserve at the bridge, but the main army under Sengbaou was disposed with strong cavalry on the flanks deployed in depth of squadrons and interspersed between the infantry battalions in and behind the villages. The Chinese front covered a distance of 5km (3 miles) but lacked substantial depth. Yet, there were significant knots of trees, which obstructed the line of sight of both armies.

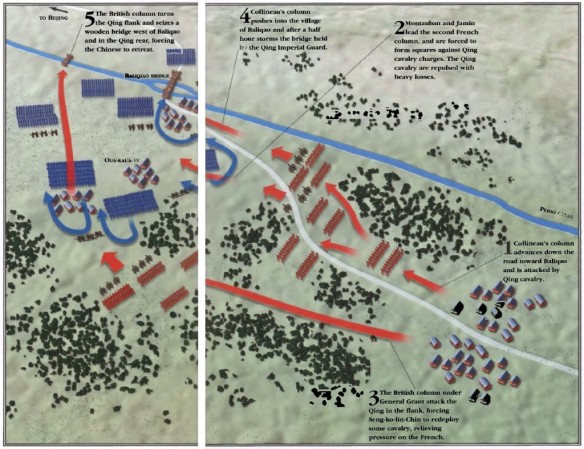

Keeping to the line of battle used at Chang chi wan, Grant took the left and Montauban the centre and right with the canal to protect his flank. Montauban used the wooded terrain to mask his paltry numbers, sending the first column in a slightly oblique attack against the Chinese centre. General Jamin would move to Collineau’s right and against the Chinese left. Grant moved to the far left of Collineau, hoping to flank the Qing army with his column. General Collineau’s advance guard comprised the elite companies of the 101st and 102nd Regiments, two companies of the 2nd Chasseurs a pied (elite light infantry), an engineer detachment, two batteries of horse artillery and a battery of 4-pound foot artillery. Montauban and Jamin commanded the 101st Regiment along with two more companies of the 2nd Chasseurs a pied, a battery of 12-pounders and a Congreve rocket section.

Collineau’s infantry advanced through the woods towards the Chinese centre. The rapidity of the movement startled Sengbaou, and he moved much of the cavalry from the wings to protect his centre. The French advance guard moved in skirmish order, and formed out along the road towards Baliqiao. Montauban ordered Jamin’s brigade forward. Two large bodies of Qing cavalry, some 12,000 in all, charged each of the French columns. Collineau’s artillery poured fire into the serried ranks of Mongol and Manchu cavalry, while the elite companies found security in the ditch that ran along the main road. Accurate fire took its toll on the cavalry, but Collineau soon found himself embroiled in hand-to-hand fighting around his position. Generals Montauban and Jamin also managed to deploy their guns and fire with devastating effect while their infantry formed two squares just before the cavalry hit their position. The French 12-pound battery was positioned between Collineau and Jamin’s brigades and continued to pour canister into the enemy. After some time, the cavalry broke off their attack, having failed to break the French squares or overrun Collineau’s precarious position. The respite allowed Montauban to take stock, re-form and advance upon the villages held by the Green Standard battalions.

Cavalry Redeployed

Sengbaou and Seng-ko-lin-ch’in did not renew their cavalry assault, as Grant’s column moved against their right. Montauban could not see the British advance because he was in one of the squares during the attack. Grant’s appearance forced the Qing generals to redeploy their cavalry to the flank, thereby allowing Montauban to attack the village closest to the centre. With an abundance of cavalry, it remains unclear why Singbaou or Seng-ko-lin-ch’in did not leave a substantial body to retard the advance of the French. Grant’s force was larger, had more guns and cavalry, and one can only surmise that they perceived this threat to the flank as a priority and underestimated the elan of the French assault.

The 101st stormed the village of Oua-kaua-ye in the centre, dispersing with ease the infantry defending it, and suffering little from their ineffective artillery. Following up, Montauban ordered both brigades to attack the village of Baliqiao, which was defended by more determined troops. Qing infantry defended the road across which Collineau advanced. His elite companies made short and bloody work of these soldiers and continued towards the village. Large cannon in the streets and across the canal fired on the French columns. Jamin brought up his batteries to silence the Chinese guns while the infantry moved in from two directions. The village and bridge at Baliqiao were defended by the Imperial Guard. These soldiers did not give ground. Collineau brought his cannon up to form crossfire with Jamin’s batteries.

Collineau Storms the Village

After tearing the Imperial Guard troops apart, Collineau formed his troops into an attack column and stormed the village. Fighting raged at close quarters for more than 30 minutes. Montauban led the 101st to Collineau’s support securing the village. Not wanting to lose momentum, Collineau re-formed his command and advanced rapidly upon the bridge, with the French batteries providing effective and deadly fire. The Chinese artillerists manning their guns were killed, and the Imperial Guard gave ground under the canister, followed by Collineau’s attack. The bridge was taken.

Grant’s column helped the Chinese along as its attack on the left dislodged the Green Standard troops from their village, while the British and Indian cavalry rolled up the line, overwhelming Qing cavalry that tried to hold their ground. The British attack was swift, but hard-fought. Grant’s line of attack brought him within sight of a wooden bridge that crossed the canal some 1.6km (1 mile) west of Baliqiao.The arrival of the British on Seng-ko-lin-ch’in’s far right, and the collapse of his forces in the face of their attack, compelled the general to pull his army from the field before it was trapped on the far bank of the canal. By noon, only five hours after the battle began, Grant’s British were on the far side of the canal across the wooden bridge, while Collineau’s elite companies established a bridgehead at Baliqiao. The victory sealed the fate of the imperial government.

The Allied expedition sacked the Imperial Summer Palace northwest of Beijing, and the emperor capitulated to European demands. Napoleon III, flush with victory over Austria the year before, rewarded Montauban with elevation to the rank of Count of the Empire, as Comte de Palikao’. Little did Montauban know that he would end his illustrious career as Minister of War in 1870, presiding over the collapse of the Second Empire and the fall of France to German armies.