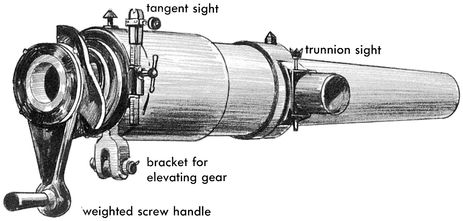

Armstrong 12-Pounder Breechloader—Cutaway Views

ARMSTRONG BREECHLOADER

The breechblock or ventpiece was held in place by a powerful screw in the rear of the gun. This screw was hollow, and was a prolongation of the bore. When the screw was turned out, the ventpiece was lifted out by its handle, leaving the bore clear for loading. To ensure the tight turning up of the screw, and also to help in releasing it when getting ready to reload, a weighted, free-swinging handle was attached to the rear of the breech. A half turn on this acted almost like a blow from a sledge and was sufficient to drive the screw well home or to start it from the closed position. Although a spare ventpiece was usually provided with each gun, there was considerable trouble with the ventpieces fracturing, or blowing out, especially in the guns of large caliber. Structurally, the built-up Armstrong gun tubes were very strong, and the multi-grooved system of rifling is in use today.

12-POUNDER WHITWORTH BREECH-AND MUZZLE-LOADING FIELD GUN

The Whitworth breechloader, with its peculiar hexagonal bore, used a device resembling a hinged screw cap. The cartridge was in a hexagonally-shaped tin container which assisted in preventing the escape of gas from the breech. A lubricating wad (tallow and wax was used) was inserted behind the projectile.

The projectile was a mechanical fit and did not rely on expansion to make a tight fit in the bore. Because of this, and because there was no chamber, by closing the breech and using a copper disc as a gas check, the guns could be (and often were) used as muzzle-loaders. This could not be done in the Armstrong, with its lead-coated shell and powder chamber larger than bore size.

RIFLED FIELD PIECES USED BY FEDERAL AND CONFEDERATE ARTILLERY

Although there were two schools of thought as to the effectiveness of rifled versus smoothbore guns, there was no question as to the greater accuracy of the rifle. There was also a marked increase in efficiency. A 12-pounder James, for instance, weighed less than a 12-pounder Napoleon and attained greater range and accuracy with a much smaller powder charge. Part of this was due to the reduction of windage.

Windage (the difference between the diameter of the shot and that of the bore) was allowed to take care of rust, the straps on the sabot, the expansion of the shot, and for ease in loading in a foul bore. It amounted to one-tenth of an inch in a 12-pounder smoothbore, and resulted in loss of accuracy as well as loss of velocity, since much of the force of the explosion of the charge was wasted.

In wooded country, the 12-pounder smoothbores had an advantage. Their accuracy was of secondary importance, and at close range their larger bores could inflict more damage than the 3-inch rifles. As the Napoleons used fixed ammunition and the rifles, semi-fixed—that is, the projectile and the charge were loaded separately—the smoothbore had a higher rate of fire. The 3-inch canister was fixed, however, with forty-nine .96 caliber iron balls in a tinned iron case, although it was claimed that, being long and thin, the load did not perform as well as that of the 12-pounder.

Of the many types of rifled pieces used in the war, the 3-inch Ordnance and the 10-pounder, 3-inch Parrott were the most popular. Originally the Parrott had been made in 2.9 caliber, but it was later changed so that the same ammunition might be used in both pieces. The Ordnance gun was of wrought iron while the Parrott had a cast-iron tube, reinforced at the breech by a wrought-iron hoop.

BREECHLOADERS

Few breechloaders were used in the Civil War (for their breech mechanisms were relatively clumsy and complicated), but the two that did see service—the Armstrong and the Whitworth—were a great deal more accurate than any of the muzzle-loading smoothbore field pieces. The Armstrong is reported to have been more than fifty times as accurate as the standard British smoothbore field piece at one thousand yards. The Whitworth was every bit as accurate. Both had considerable range with low elevation, which meant a larger “danger space.” But long range (the Whitworth 12-pounder could send a bolt nearly six miles) was not of much advantage in the days of imperfect means of observation and poor fire control, and small-caliber shells with comparatively weak bursting charges.

Neither of these breechloaders had any great advantage over muzzle-loaders in rapidity of fire (for one thing, neither used fixed ammunition). A light rifle and shrapnel-proof gun shield, as used in more modern field pieces, might have increased their value, as the gun crews could have been partially protected from musketry. But this did not come into being until the development of a workable recoil mechanism.