The life-and-death demands of war forced the pace of technological innovation. As the summer progressed, a new development emerged that was to alter the balance dramatically in the enemy’s favour. It ushered in a period of the air war that became known as the ‘Fokker menace’ and it began in an almost accidental fashion. Roland Garros was a French aerial trailblazer, the first man to fly the Mediterranean. In 1915 he and the designer Raymond Saulnier set about trying to solve the problem of how to fit a machine gun to an aeroplane that could be fired straight ahead without the gymnastics required to operate a wing-fixed weapon. The main difficulty seemed to be the obstacle presented by the whirring propeller, oscillating at 2,000 revolutions a minute. But the pair decided that, unlikely though it might seem, most of the bullets could pass through its arc without striking the twin blades. Those that did hit could be deflected without doing damage by fitting wedge-shaped metal plates.

On 1 April Garros tried out a prototype and promptly shot down a two-seater. In the next seventeen days he repeated the performance twice. The device was fitted to other aircraft and other pilots repeated his success. Then Garros was shot down. He was too late to set fire to his machine and the wonder gadget fell into German hands. The propeller was handed over to a Dutch aircraft designer, Anthony Fokker, who was working with the Germans. On examining it they were reminded of a pre-war patent – which almost incredibly had been overlooked – for a synchronized gun with an interrupter gear, which timed the stream of bullets so they passed through the spaces between the blades. They revived it and tested it. It worked. The deflector plates became instantly obsolete.

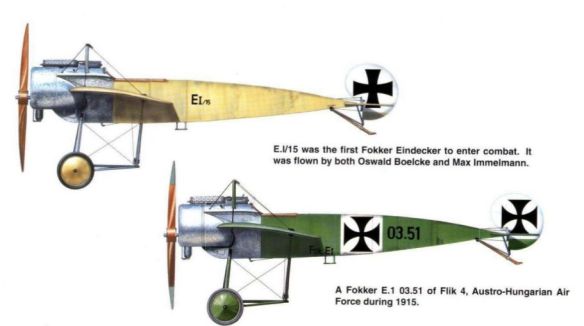

Fokker developed a new aeroplane, the Eindecker E1 monoplane, on which to mount the new weapon system. Now a pilot had only to point his machine in the direction of his enemy to threaten him. Fokker had developed what was, in effect, a flying gun – the first efficient fighter aeroplane. The first few Fokker Eindeckers or E1s began to appear in July 1915, operating in pairs as defensive escorts for patrol aircraft. It was a little while before the Germans realized their offensive capability. It was pilots, rather than commanders, who grasped their potential. They were led by Oswald Boelcke, who had worked with another soon-to-be famous airman Max Immelman, with Fokker on the development of the E1.

Historians later claimed that despite its reputation the Eindecker was nothing special. However, Ira Jones, a young Welsh mechanic who went on to fly with 56 (‘Tiger’) Squadron and was credited with shooting down forty enemy aircraft, saw it in action and had a due respect for its qualities. It was a ‘fast, good climbing, strong-structured, highly manoeuvrable aeroplane – all essential qualities of an efficient fighting machine. When flown by such masterly, determined pilots as Boelcke and Immelmann it was almost invincible.’ During the autumn British pilots came to fear these two names.

Max Immelman was born into a family of wealthy industrialists in Dresden. He perfected a manoeuvre of diving, climbing and flicking over, ready to attack again, which became known as the ‘Immelmann turn’. Oswald Boelcke was the son of a militaristic schoolmaster. He overcame childhood asthma to become an excellent sportsman. He was as diligent in the classroom as on the playing field, and most enjoyed mathematics. According to Johnny Johnson, one of the great British aces of the next conflict, he was ‘a splendid fighter pilot, an outstanding leader and a tactician of rare quality . . . his foes held him in high regard.’ Boelcke brought a scientific coolness to air fighting, codifying tactics in a book called the Dicta Boelcke. He laid down four basic principles: (1) the higher your aeroplane, the greater your advantage; (2) attack with the sun behind you, so you are invisible to your opponent; (3) use cloud to hide in; and (4) get in as close as possible. They sound simple, but in the sudden chaos that characterized fights, these rules were easily forgotten.

For all his professionalism he enjoyed the kill, as is apparent from his description of the downing of an unsuspecting Vickers ‘Gunbus’. Boelcke was flying at 3,500 feet when he saw the enemy aircraft fly over the lines at Arras and head for Cambrai. He crept in behind it unseen and followed for a while. His fingers were ‘itching to shoot’, but he controlled himself.

‘[I] withheld my fire until I was within 60 metres of him,’ he wrote afterwards. ‘I could plainly see the observer in the front seat peering out downward. Knack-knack-knack . . . went my gun. Fifty rounds, and then a long flame shot out of his engine. Another fifty rounds at the pilot. Now his fate was sealed. He went down in long spirals to land. Almost every bullet of my first series went home. Elevator, rudder, wings, engine, tank and control wires were shot up.’Surprisingly, both the pilot, Captain Charles Darley, and the observer, Lieutenant R. J. Slade, survived.

As the war entered a new year, it was vital to come up with a means of countering the German challenge if the British and French air forces were not to be cleared from the skies. Trenchard was determined that patrols should continue despite the threat. His solution was to provide a cluster of escorts for each reconnaissance flight. The method soaked up resources. On one flight, on 7 February 1916, a single BE2C from 12 Squadron took off, accompanied by twelve other aircraft. The approach was unsustainable.

Eventually Allied technology came up with an antidote to the Fokker and the menace subsided. In the spring of 1916 the trim French Nieuport 11, nicknamed the ‘Bébé’, began to arrive on British squadrons. Its Lewis gun was fixed on the top wing, but it was more agile than the E1 and good pilots could get the better of it. The ‘Bébé’ was joined by another French type, produced by the French firm SPAD, which carried a synchronized Vickers gun. The second-generation pusher types – the DH2s and robust FE2 ‘Fees’ also learned how to cope and even prevail, exploiting the fact that the gunner, perched in the front nacelle, had a wide field of fire and his weapon laid down a more rapid stream of bullets than the armament of the Fokker, which was slowed by the interrupter gear. It was a Fee that did for Max Immelmann, who was brought down by the fire of Corporal J. H. Waller, an observer with 25 Squadron, on 18 June 1916 over the village of Lentz, shortly after he had scored his seventeenth victory. The appearance of the excellent two-man Sopwith ‘1½ Strutter’, which combined a synchronized Vickers for the pilot and a Lewis for the observer, helped to turn the tide.