Second Day: Monday, 24 June, Feast of John the Baptist

As the first rays of morning sunshine began to insinuate among the trees of the Torwod the English army, drawn up on the north bank of the Bannock Burn, witnessed a sight they had not expected to see. The entire Scottish army began to emerge from the woods, in full view. Then, in the growing light of the summer sun, thousands of Scots suddenly fell on their knees to celebrate Mass led by the Abbott of Inchaffray who then delivered a speech urging the Scots to fight for their freedom. The sudden appearance of the Scots took the English completely by surprise. On seeing the entire Scottish host drop to its knees, Edward asked his companion, Sir Ingram de Umfraville, a traitor Scot, if the Scots intended to fight, then he joked that Bruce’s men were begging for mercy. De Umfraville did not hesitate in his answer, saying that the Scots were not asking for mercy from Edward but from God for what they were about to do.

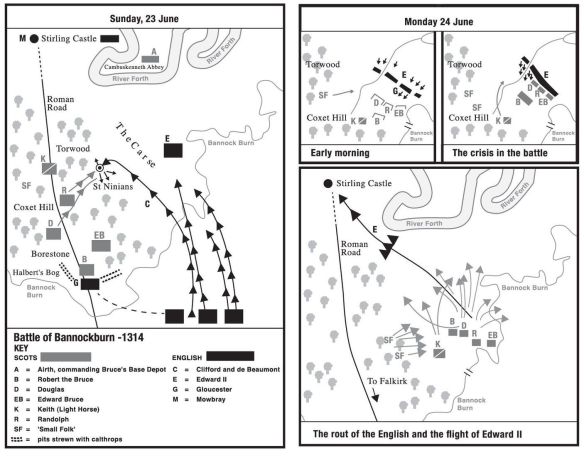

The English knights hastily made the final preparations for a battle they had not expected to fight that early morning. At the head of the vanguard flew the banners of Gloucester and Hereford; the main division led by Edward hoisted the royal standard of the Plantagenet king with its device of three gold lions or leopards on a field of crimson. Opposite, a great mast bore the royal standard of Scotland, a red lion rampant with a red bordure on a field of gold. Bruce positioned his three divisions with Randolph’s and Edward Bruce’s abreast, the two forming a Scottish front line several ranks deep, about 6,000 spearmen. Bruce took up his position in the rear along with Sir Robert Keith’s mobile unit of 500 light horse, ready to deploy wherever the English looked like outflanking Bruce’s two main columns. Then Bruce ordered the Scots to advance at a measured pace towards the English vanguard.

There was considerable consternation in the English front lines of horsed knights and men-at-arms. Apart from the astonishing spectacle of finding the Scots still to their front after the previous day’s skirmishing, some voiced their opinion that it was bad luck to fight on the day of the Feast of St John the Baptist and that the king should wait until the following day. Unsurprisingly, it was not the young, inexperienced knights who voiced this opinion but the veterans. Their plea for delay attracted scorn from the younger men who were anxious to gain honours for themselves. Chief among those countenancing caution was the Earl of Gloucester who made his disquiet known to Edward as to the state of mind in the army as well as arguing that Edward should respect the feast day. The English king was in no mood to entertain suggestions that he should delay the action. Edward even accused Gloucester of treachery and deceit when his leading commander begged him to wait until the next morning to attack Bruce. Gloucester responded by saying he was neither traitor nor liar, returning sullenly to the vanguard he commanded. It was evident that there was unrest in the high command and that veterans like Gloucester were showing signs of breaking under pressure.

As the Scottish army slowly but steadily advanced, the knights and men-at-arms made their final preparations to engage Bruce’s men. From their position, with the sun at their backs on that longest day – it is reckoned that Bannockburn was fought and won before 9am – the English cavalry could clearly see the thousands of Scottish foot soldiers, a solid mass bristling with spears. Curiously, despite the vital role the English archers had played in earlier battles such as Falkirk, they were hardly used in the battle, although some sources credit them with a role. Barbour’s The Brus has the English bowmen driven from the field by Robert Keith’s light cavalry but this is not confirmed by other accounts. If Edwards’s archers were engaged at all, it was against the smaller formation of Scottish archers who had the benefit of striking home with their arrows more than the English bowmen, whose arrows were embedded in nothing more than the stout trees in the woods.

Leading the vanguard of the English heavy cavalry, Gloucester and Hereford ordered their knights and men-at-arms to advance at the trot, then a canter until the order to level lances was given, probably by the sound of a recognizable trumpet call. From the outset the ground Bruce had chosen to fight the battle discomfited the English heavy horse which could neither deploy nor avoid bunching up in a heaving mass of men and horses. The already crumbling unity of Edward’s cavalry was compounded by the arrival of contingents of English foot soldiers. The Scottish schiltrons were packed so tight that they advanced like a thickset hedge which could not be breached. Then, suddenly, the Scottish spearmen halted, readying themselves for Edward’s by now charging cavalry, their lances levelled. The Earl of Gloucester was in the forefront; as he closed in on the Scottish vanguard he would have been close enough to see the grim, determined faces of the Scots in the front ranks, their spears bristling like a hedgehog. The English vanguard slammed into the solid phalanxes of Scots, a sickening, bone-crunching collision, with horses impaled on spears. Knights and men-at-arms were thrown to the ground, suffocating under the weight of their armour and the bodies of men and horses which began to pile up on them. Lances and spears that found their mark snapped in two, blood flew in the air, spraying both sides.

Gloucester had engaged Edward Bruce’s division on the Scottish right wing. On the left Randolph braced himself for the coming impact, the English waves breaking on the rock that was Bruce’s army. Moments after the English vanguard had smashed into the Scottish front line the main cavalry attack was launched, which rocked the Scottish spearmen. The foremost ranks began to show signs of crumbling, but Randolph rallied his men; the schiltrons all along the line held fast. Many English knights never struck a single blow that early June morning simply because in that close-packed, heaving mass of men and horses, they had no room even to draw sword. The grass grew slippery with blood, the waters of the Bannock Burn began to change colour …

The battle was now raging out of control of both Bruce and Edward II. It had degenerated into a desperate, vicious hand-to-hand fracas, a frenzy of men indiscriminately hacking each other to pieces. In the melee Gloucester was somehow isolated and found himself alone; a body of Scots rushed forward, slaying his horse and dragging him to the ground where he lay helpless, unable to rise on account of the weight of his armour. The Scots offered no quarter; when Gloucester’s body was retrieved later it bore a multitude of wounds. At the height of their blood-lust the Scots were clearly not taking prisoners, not even men as rich in ransom money as Gloucester. The English onlookers must have been devastated by the sight of a prominent noble of England being slaughtered, the first time this had occurred for many years; added to this was the ignominy of the rank of Gloucester’s slayers, mere common foot soldiers and countryfolk.

The constricted area of the field was now beginning to tell on Edward’s army, restricting its ability to manoeuvre; weight of numbers was becoming a hindrance. Some three English cavalry divisions, numbering about 5,000, had attacked the Scottish lines but failed to shatter their ranks. Behind them the rear echelons of perhaps a further 1,000 knights and men-at-arms pressed forward in their eagerness to join the fight. Beyond them the massed infantry closed in behind. The narrowness of the field caused the cavalry to bunch up; thus disorganized and constricted, the knights and men-at-arms to the forefront were literally driven on to the spears of the Scottish schiltrons. With the weight of those pressing from behind, English casualties began to mount up dangerously. Another disaster came with the death of Robert Clifford, perhaps desperate to save face after his defeat by Randolph the previous day. In that cauldron of slaughter, the loss of one man was of little import; there was only brief mention made of his death.

Trouble began to accumulate for Edward II; this time it came from the distant rear where thousands of troops as yet uncommitted to battle could hear but not see what was happening in the battle raging on the north bank of the Bannock Burn. Morale among the infantrymen was already low; they had learnt of the poor showing of the knights the previous day, nor was there any prospect of booty or renown for them even if Edward won the battle. It was at this point that an unplanned,unexpected but dramatic event took place on the Scottish side. Suddenly, a fresh army – or so it seemed to the disbelieving English – appeared from behind either the nearby Coxet or Gillies’ Hills. It was the ‘Small Folk’ – those given the task of guarding the Scottish baggage train – who came streaming over the hill bearing ‘banners’ – common camp blankets nailed to poles, hoping to enrich themselves by plundering the English dead and Edward’s huge baggage train. Some imaginative students of Scottish history interested in this aspect of Bannockburn have hazarded a theory that among the ‘Small Folk’ was a contingent of Knights Templars, the Military Order which had played a large part in European conflicts in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, particularly during the Crusades. Although sworn to chastity, poverty and obedience, the Order had grown over-mighty and wealthy, which had aroused jealousy and ill-will, especially among the hierarchy of senior clergymen, including the Pope himself. Philip IV of France was resolved to enrich himself with their possessions and obtained the consent to proceed thus by Pope Clement V whom he had placed on the Papal Throne. The French Templars were arrested and subjected to extreme torture by which was extracted evidence of outrageous moral offences and grave heresies. The Order was suppressed by Clement V in England, France, Spain, Portugal, Germany and Italy but, for some reason, not Scotland. As Bruce was under excommunication for his murder of the Red Comyn in 1306, some believe that he condoned those Templars living in Scotland and even invited the excommunicated Templars in Europe to settle in Scotland. There is no evidence to support the theory that they were present on the field of Bannockburn at Bruce’s side. If they had been, the appearance of even a small group of these medieval warriors in their distinctive white linen mantles with a red cross emblazoned on the left shoulder would have struck terror in the English army that day. The hard-nosed historian is unlikely to accept this theory, compelling though it is.

By now the crumbling English morale finally collapsed. Men began to drift away from the battle, crossing the Bannock Burn in droves. Crossing is too simple a word to describe the panic of the demoralized English; many fell into the waters of the deep ditch, drowning instantly, their bodies acting as a human bridge for those following and trampling them in their haste to gain the other steep side of the burn.

Despite the obvious fact that his battle was lost Edward II refused to concede victory to Bruce, nor quit the field. Aymer de Valence and a knight, Giles d’Argentan, entrusted with Edward’s safety, urged the King to depart the field. Were the king to be killed or taken prisoner the ignominy was too appalling to contemplate. Edward was led forcibly from the field, his guardians holding the reins of his war-horse. The Scots were menacingly close and could have easily overtaken the three men. Once Edward was joined by his royal retinue and a body of 500 cavalry, d’Argentan considered he had fulfilled his duty to the king. Turning his horse to face the Scots, he galloped into their midst and was dragged from his mount, then unceremoniously hacked to pieces.

Those English who managed to extricate themselves from this bloodiest of killing fields in the history of Scotland scrambled through marsh, plunging into stream and river, pursued by an uncontrollable horde of screaming Scottish spearmen intent on despatching as many as they could; they were determined that Bannockburn would finally finish the war and bring them freedom from English domination. Edward II ran with his demoralized troops, hoping to gain sanctuary in Stirling Castle. When he arrived at the gates he found them closed. The castle’s constable, Philip de Mowbray, had a ringside seat at Bannockburn; from the battlements he watched the horrifying spectacle unfold. He knew that his king had lost not only a battle but, also, under the laws of chivalry, he must in all conscience surrender Stirling Castle to Edward Bruce. De Mowbray duly did so, leaving Edward with no other option but to make his way to safety in the south as best as he could.

On the battlefield the Scots rounded up the important prisoners who would be ransomed, or become hostages to allow Bruce to negotiate for the release of his queen and family who had remained in English custody since 1307. This occurred in due course. Among the first of Bruce’s womenfolk to be released were his queen, Elizabeth de Burgh, his daughter Marjorie and his sister Christian. But that was in the future; Bruce was anxious to crown his spectacular victory with the ultimate prize – Edward II himself.

The terrified and frustrated king forced his way through the shattered remnants of his army with 500 horse, galloping to the one place he could expect refuge, the castle of Patrick, Earl of Dunbar. Edward was hotly pursued by the ‘Good Sir James’ (the Black Douglas), with only eighty light horse. Edward could have easily turned and stood against Douglas but he believed Sir James was only the vanguard of a much larger force of Scottish cavalry. Douglas pressed the fleeing English so relentlessly that they were unable to ‘make water’ i.e. attend to the call of nature.

With a greatly reduced escort – many of his men had deserted en route to Dunbar – Edward managed to reach the safety of Dunbar Castle, vanishing within its walls where Patrick Dunbar received him ‘full gently’. However, shocked by and apprehensive about Edward’s defeat, Dunbar could only offer the king a boat to take him to safety in Berwick. It is fruitless to speculate on the conversation which took place between Edward and Dunbar that day. Scalacronica, Sir Thomas de Gray’s account of Bannockburn written forty-two years later, stated that those closest to Edward who escaped with him to Dunbar were saved but the rest came to grief. Patrick Dunbar received the king honourably and, under feudal law, offered Edward his castle, even removing his own family and household. This was no altruistic gesture on Dunbar’s part; there was no doubt nor suspicion that Dunbar would do anything less than his ‘devoir [duty], for at that time he was Edward’s liegeman’. From Dunbar, Edward sailed to Berwick, then south. Even after Edward’s defeat the Earl of Dunbar briefly remained loyal to England; he would soon discover how lightly Edward valued his loyalty.

A contemporary account of Bannockburn stated that:

Our costly belongings were ravished to the value of £20,000; so many fine noblemen and valiant youth … all lost in one unfortunate day, one fleeting hour … Assuredly the proud arrogance of our men made the Scots rejoice in their victory.

The precise number of casualties on both sides at Bannockburn is difficult to quantify. One near contemporary account gives 30,000 English dead, a ridiculously over-inflated figure which has been challenged by historians closer to our own time.33 A recent excellent account of Bannockburn by David Cornell lists forty-seven men of the rank of knight and above in an appendix to his book Bannockburn: The Triumph of Robert the Bruce; among these are Gilbert de Clare, Earl of Gloucester, Sir Giles d’Argentan, John Comyn, Lord of Badenoch, William Deyncourt, Sir Edmund de Mauley, Steward in Edward II’s household, and Sir Henry de Bohun. Among the prominent captives were Humphrey de Bohun, Earl of Hereford, Robert de Umfraville, Earl of Angus, Ingram de Umfraville, Sir Thomas Gray of Heton, Marmaduke Twenge and Gibert de Bohun. In addition there were 700 minor nobles and several clergymen. (Most important of all the prisoners was the Earl of Hereford; he was exchanged for Bruce’s ladies, as mentioned earlier, and the elderly Robert Wishart, bishop of Glasgow.) Scottish casualties of the rank of knight and above were light; the only nobles slain were Sir William de Vieuxpont (Vipont) and Sir Walter de Ross. Cornell states that the number of casualties among the ranks of ordinary spearmen is impossible to estimate; he also points out that the majority of casualties suffered by the English were not in terms of those killed but taken prisoner although in his view an ‘unprecedented number of English bannerets (men knighted on the field) and long-established knights were slain in the engagement’ (page 234, Bannockburn). It would be a pointless exercise to attempt to quantify the number of dead on both sides; a conservative ‘guesstimate’ of ten per cent for both sides would produce fatal casualties of English at 2,500 and between 600 and 800 Scots. But this is pure conjecture on the part of the author. The bulk of the English casualties were lost not in battle but in the frenzied attempts of men to escape the field, many coming to grief in the waters of the Bannock Burn and the surrounding marshland.

Safe in England, Edward’s response to the Earl of Dunbar’s courtesy was swift and callous. Possibly persuaded by his court favourites that, in writing to the king in the autumn of 1313, Dunbar’s letter begging Edward to come north to restore order was part of Bruce’s strategy to lure Edward north and that Dunbar was in fact a traitor in English eyes. Edward was not noted for his political acumen and relied to an almost criminal degree on the advice of favourites such as Piers Gaveston, the Gascon adventurer who was murdered by Edward’s nobles in 1312 for his overbearing attitude, his influence on Edward and that king’s generosity to a man who was hated for his arrogance and undeserved wealth.

Edward II declared Patrick, 9th Earl of Dunbar a traitor to the English crown on 25 June – the day after his flight from Bannockburn. Dunbar’s English lands were declared forfeit. Dunbar was now reviled by both Scots and English; in desperation the luckless earl had no choice but to seek peace with Robert the Bruce. It says much for Bruce that he waived his own rule that the Scottish lands of every Scottish noble absent from the field of Bannockburn would be declared forfeited. For some reason we can only guess at, Dunbar was allowed to keep his titles and lands in East Lothian, Berwickshire and elsewhere; he was even made welcome at Bruce’s court.

Robert Bruce’s period of probation was now at an end. Even the English Chronicle of Lanercost described him as King of Scotland, which Edward II still refused to do. In November 1314, at Cambuskenneth Abbey, King Robert declared that those earls, barons and knights not present on the field of Bannockburn and whose fealty to England remained intact would lose their Scottish estates. These men became known as The Disinherited. That day, Bruce’s words were uncompromising; all who

had not come into his faith and peace … are to be disinherited forever of lands and tenements and all other status in the Realm of Scotland. And they are to be held in future as foes of the king and the kingdom, debarred forever from all claims of hereditary right … on behalf of themselves and their heirs.

Bruce also extended his decree to include the English lands held by Scottish nobles from Edward II so that no Scottish male (or female) could thereafter be subject to dual allegiance to Scotland and England. (This is an important point which to a great extent challenges the view of many modern historians that ownership of English lands was never a major factor in the occasional lapses of loyalty in some Scottish nobles. It must be said that Bruce had scarcely a knight or noble in his army at Bannockburn who at one time or another had not sworn allegiance to England for possessions they held south of the Border.)

The English commentators on the reasons for the defeat at Bannockburn clutched at every straw borne on the wind they could imagine. It was the drunken Welsh foot soldiers, it was poor discipline, it was over-confidence, it was unchivalric quarrelling among Edward’s commanders. The anonymous author of Vita Edwardi Secundi demanded to know why knights unconquered through the ages had run away from mere foot soldiers. The apologists did not – or would not – acknowledge the fact that it was Bruce’s excellent choice of ground and his careful preparations which had won the day; Bannockburn was the prime example of Bruce’s eye for ground favourable to him, a genius he shared with the Duke of Wellington. The terrain at Bannockburn was heavily wooded, offering cover from the English archers as well as boggy ground which reduced the effectiveness of the English heavy cavalry. Bruce was now acknowledged in Scotland as her true King.

As for Edward, he was fortunate to escape from Bannockburn, then Dunbar but this eleventh hour blessing was mixed. Departing from Dunbar by ship he was probably accompanied by Aymer de Valence and Henry de Beaumont, the future leader of Bruce’s Disinherited who would cause much trouble for Scotland in the years to come. From Berwick the three men proceeded to York where they tried to come to terms with the calamity of Bannockburn, news of which quickly spread in England, then Europe, creating shockwaves that reverberated long after the defeat. Edward’s only consolation was that his personal shield and privy seal, both lost at Bannockburn, were returned to him by the magnanimous Bruce. In doing this Bruce was exercising his diplomatic skills; having beaten Edward in open conflict, he was intent on reaching a peaceful settlement with Edward and had no desire to further ruffle the English king’s bedraggled feathers. Bruce knew that, despite his spectacular military and political success, he was in no position to dictate terms to Edward. England was still a formidable adversary and could easily raise another army against Scotland – providing Edward enjoyed the support of the English parliament which met in September 1314. That parliament was presided over by the powerful Earl of Lancaster who had not supported Edward’s invasion of Scotland. The list of prominent names of those killed or ‘missing in action’ grew (as the records of the Great War of 1914 – 18 euphemistically described those killed without trace on the Western Front) those missing after Bannockburn were thankfully found to be Bruce’s prisoners. At least that was a consolation to their families.

After Bannockburn, Edward II never again enjoyed the power he had inherited from his father Edward I, the Hammer of the Scots. After a lacklustre rule of another thirteen years, Edward II was horribly murdered by his French Queen Isabella and her lover, the Earl of Mortimer at Berkeley Castle in 1327.

Before that, Bruce now in his late forties suffered from ill health, mainly due to years of living rough and endless fighting. As yet he had produced no heir to succeed him so, to avert the chaos which followed the death of Alexander III in 1286, an assembly was convened at Ayr in April 1315 to settle the succession question. Should Bruce die without a male heir it was agreed that he would be succeeded by his brother Edward and his heirs male. As a contingency, in the event of a ruler in his minority, Thomas Randolph, Earl of Moray would be appointed regent to administer the country. In 1315 Bruce’s daughter Marjorie by his first wife took as husband Walter, High Steward of Scotland. Pregnant in 1316, Marjorie died after a fall from her horse but her baby survived. Named Robert after his grandfather the King, the baby was declared heir presumptive to the throne of Scotland in 1318. The succession question was resolved in 1324 when Bruce’s queen, Elizabeth, gave birth to their son David.

Bruce carried the war to England yet again hoping to bring Edward II to the negotiating table and acknowledge him as rightful king of a free and independent Scotland. At the same time the Irish in Ulster opened negotiations with Bruce to assist them in their struggle with England; this gave Bruce yet another opportunity to carry his war against another part of Edward II’s empire. (It was announced that if Ireland fell to the Scots, Wales would be next.) In May 1315 Bruce’s brother Edward landed at Carrickfergus with an army of 6,000; he had varying successes against the English there, although he was crowned King of Ireland in 1316. During that year and the next Robert Bruce was in Ireland supporting his brother.