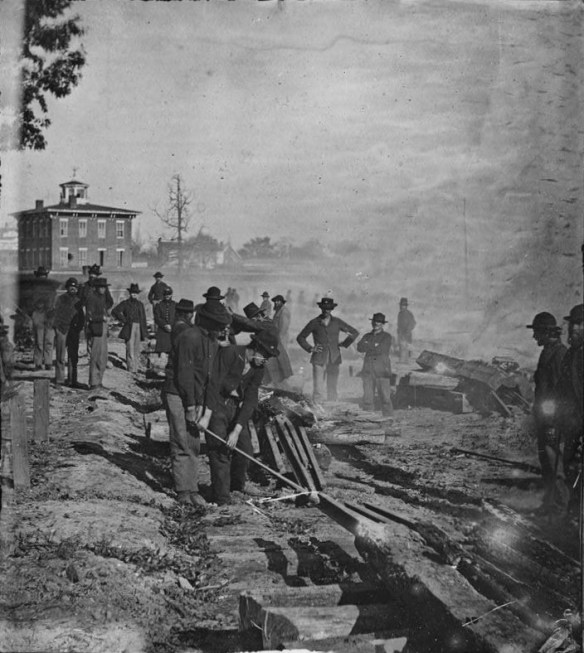

Sherman’s men destroying a railroad in Atlanta.

Map of Sherman’s campaigns in Georgia and the Carolinas, 1864–1865.

General William Tecumseh Sherman, who had been left by Grant to command in the West—a term used during the war to signify the campaigns not fought in Virginia, Maryland, and Pennsylvania, but geographically in the beginnings of the Deep South—received on April 4 and 19 two letters in which Grant outlined his plans for the conclusion of the western campaign. Grant’s order to Sherman and his armies in Tennessee for the campaign of 1864-65 had been to “move against Johnston’s army, to break it up and to get into the interior of the enemy’s country as far as you can, inflicting all the damage you can against their war resources.” In addition to the Army of the Potomac, Grant had three other armies to employ in 1864: those of Banks at New Orleans, Butler on the Virginia coast, and Sigel in West Virginia. Sigel was responsible for the Shenandoah Valley, from which Lee drew many of his supplies; Butler was to operate on the James River near Richmond, with the object of cutting the city’s rail communications with the rest of the Confederacy; Banks, Grant hoped, would get into Mississippi and seize Mobile, an important naval and rail centre.

The key operation, however, was that of Sherman, who commanded, as a combined force, McPherson’s own Army of the Tennessee (24,465), Thomas’s Army of the Cumberland (60,773), and John Schofield’s Army of the Ohio (13,559), total strength 98,797. Its task looked simple enough: to push forward from the neighbourhood of Dalton to Atlanta, ninety miles to the south, dispersing Johnston’s Army of Tennessee, only 60,000 strong, and beating its component units as he went. Easier said than done. Part of Sherman’s problem was his very long and attenuated line of communications, which stretched back along the Western and Atlantic Railroad 470 miles to his main base at Louisville, Kentucky, much of its length running through hostile or at least dangerous territory. Forward of Dalton, moreover, the defenders enjoyed the use of several strong defensible features, notably the Oostanaula, Etowah, and Chattahoochee rivers and the steep slope of Kennesaw Mountain. Johnston’s favoured strategy, moreover, was perfectly suited to the terrain, since he believed in avoiding battle when possible and extracting advantage by manoeuvre.

Sherman began his advance into the South on May 4, 1864, leaving Chattanooga to confront Johnston on the route that led to Atlanta (not then Georgia’s state capital, which was Milledgeville). The fighting opened at Tunnel Hill, one of the features of Lookout Mountain, captured by Sherman the previous month. After some vigorous outpost skirmishing, Thomas, with General Oliver Howard, one of his corps commanders, spent May 7 and 8 trying to clear the Confederates off the high ground, so as to open a way forward. Johnston opposed him very effectively, until McPherson, whose corps was principally engaged, was forced to withdraw and wait between Sugar Hill and Buzzard-Roost Gap for a better opportunity. Johnston denied one until May 12, when, in what Howard called “one of his clean retreats,” he left the way open. Sherman’s men caught up with his at Resaca on May 14 and found that by entrenchment and barricading, Johnston had made the position as strong, in Howard’s opinion, as Marye’s Heights at Fredericksburg. While the army was advancing, Sherman, who had spent the night at his map table, took the opportunity to snatch a nap against a tree trunk. A passing soldier remarked, “A pretty way we are commanded.” Sherman, who was less asleep than he appeared, called out, “Stop, my man. While you were sleeping last night, I was planning for you, sir; and now I was taking a nap.” Least pompous of men, Sherman left the exchange there. He was sometimes mistaken for a young junior officer, since he stood less than five feet, six inches tall and weighed under 150 pounds.

The Confederate commander opposite at Resaca was Leonidas Polk, the Episcopalian bishop-turned-general. During the evening of May 14, he attempted to drive McPherson’s men away, but his effort was defeated. The Confederates lost 2,800 men to the Union’s 2,747 at the battle of Resaca. Sherman had a thoroughly realistic attitude towards losses: “A certain amount of … killing had to be done, to accomplish the end.” At Resaca Sherman fought offensively, Johnston defensively, aided by earthen parapets. Johnston then fell back to Calhoun, Adairsville, and Cassville, where he halted for the battle of the campaign, but then he continued his retreat beyond the next spur of the Appalachian chain to Allatoona.

Sherman, who knew Allatoona from a previous visit, decided not to fight there. After repairing the railroad he pushed on to Atlanta by way of Dallas. Johnston divined Sherman’s intention and forced him to fight at New Hope Church on May 25-28, a slight Union victory. Sherman remarked that “the country was almost in a state of nature—with few or no roads, nothing that a European could understand.” Johnston continued to retreat, picking up reinforcements as he went to raise his strength to 62,000. His route took him to Marietta, between Brush Mountain and Lost Mountain. Johnston’s line was too long for his numbers so he drew in his flanks and concentrated on Kennesaw. Sherman repaired the railroad up to his camp, awaiting a battle he knew must come. During the preliminaries, there was continuous skirmishing, with the batteries and line of battle pushed right forward. Sherman’s effort to carry the Kennesaw position failed, however, with a Union loss of 3,000 to the Confederates’ 630. Yet Johnston was so shaken that he abandoned his lines and retreated to the Chattahoochee River. After a skirmish at Smyrna Church, he was driven across the Chattahoochee on July 10. Sherman paid tribute to Johnston’s conduct of the retreat, saying his movements were “timely, in good order and he left nothing behind.” The Union “had advanced into the enemy’s country 120 miles, with a single-track railroad which had to bring clothing, food, ammunition, everything requisite for 100,000 men and 23,000 animals. The city of Atlanta, the gate city opening the interior of the important State of Georgia, was in sight; its protecting army was shaken but not defeated, and onward we had to go,” illustrating the principle that “an army once on the offensive must maintain the offensive.”

The fighting along the Oostanaula River was heavy. On July 15, Sherman committed the troops commanded by Hooker, who since being relieved of command of the Army of the Potomac had reverted to corps commander, with remarkable equanimity. After a heavy day’s fighting, he carried most of the ground before him. Sherman committed cavalry and laid pontoons over the Oostanaula, thereby achieving superiority of numbers. During the night Johnston decided he could no longer hold the Resaca position and withdrew the Army of Tennessee. In the day following, the Confederates completed an extended withdrawal, to the line of Rome-Kingston-Cassville, along the Etowah River. Oliver Howard, with Sherman in his command party, pressed forward and was fired upon by rebel artillery, which killed several Union horses. The enemy, however, was now badly demoralised by the successful Union advance from Resaca. Howard captured about 4,000 prisoners, including a whole regiment.

His engineers were also energetically repairing the railroad running back to Nashville and Louisville. On the morning of July 18, word arrived by the repaired telegraph from Resaca that bacon, hardtack, and coffee, the essentials of the Union soldier’s fare, were already arriving. The Confederates continued to fall back, all the more eagerly when Johnston, on the Etowah, discovered that the Union’s advance guards were south of him in force at Cartersville and Kingston, where Sherman had set up his headquarters. General Howard found the countryside of farm and woodland about here so picturesque that it was as if there were no war, and the surroundings encouraged Sherman to give his troops three days’ rest. Nevertheless, the abundance of timber allowed both armies to construct strong defences both in attack and defence and, when fighting broke out, to inflict heavy casualties on each other. It was in this region that, as Sherman pressed his advance towards Atlanta, Bishop Polk was shot through the body by an artillery round, dying instantly. By further disengagement, Johnston had now established his line on high ground at Kennesaw Mountain, one of the last peaks of the Appalachian chain, an obstacle which at last gave him a holding place Sherman could not turn. Sherman was in practice more concerned with Hood’s suddenly evinced determination to cut the Army of the Tennessee’s connection with its distant base, an aim that had drawn Nathan Bedford Forrest’s cavalry into an attack on the Union’s railroad link. Sherman had despatched a counter-attack force from Memphis to run Forrest down, angrily proclaiming that there would never be peace in Tennessee until Forrest was dead. The Memphis force brought Forrest to battle at Brice’s Crossroads in Mississippi, where it was badly defeated. At a second encounter Forrest was defeated at Tupelo and wounded, but he did not die. There was a lot of life in the old hellhound yet.

Johnston’s success in holding the Kennesaw position came, however, too late to save his own position. Jefferson Davis had an old grudge against him, over a trifling dispute about rank, but the real cause of his fall was popular dissatisfaction with his strategy of evasion and delay, which was almost universally misunderstood as reluctance to risk battle. He was now removed from command in the West and replaced by Lieutenant General John Bell Hood, who, by contrast, was aggressive, bold, and personally brave. Sherman, a friend and intimate of Grant’s recorded his feelings as he embarked on his first major independent campaign:

We were as brothers, I the older man in years, he [Grant] the higher in rank. We both believed in our hearts that the success of the Union cause was necessary not only to the then generation of Americans, but to all future generations. We both professed to be gentlemen and professional soldiers, educated in the science of war by our generous government for the very occasion which had arisen. Neither of us by nature was a combatative man [this was disingenuous of Sherman since the two were to prove themselves the most ruthless commanders of the whole war]; but with honest hearts and a clear purpose to do what man could, we embarked on that campaign which I believe, in its strategy, in its logistics, in its grand and minor tactics, had added new luster to the old science of war. Both of us had at our front generals [Lee and Johnston, then Hood, respectively] to whom in early life we had been taught to look up to,—educated and experienced soldiers like ourselves, not likely to make any mistakes, and each of whom had as strong an army as could be collected from the mass of the Southern people,—of the same blood as ourselves, brave, confident, and well-equipped; in addition to which they had the most decided advantage of operating in their own difficult country of mountain, forest, ravine and river, affording admirable opportunities for defense, besides the other equally important advantage that we had to invade the country of our unqualified enemy, and expose our long lines of supply to guerrillas of an “exasperated people.” Again, as we advanced we had to leave guards to bridges, stations and intermediate depots, diminishing the fighting force, while our enemy gained strength, by picking up his detachments as he fell back, and had railroads to bring supplies and reinforcements from his rear. I instance these facts to offset the common assertion that we of the North won the war by brute force and not by courage and skill.

Johnston’s last act before his dismissal was to defend the earthworks he had built at the crossings over the Chattahoochee above Atlanta, which the Union overcame by finding crossings elsewhere, and then to withdraw into the defences of Atlanta itself. His conduct in the preceding weeks had been by no means contemptible; he had forced Sherman to spend seventy-four days in advancing a hundred miles, and was still in fighting form.