There were other, more positive reasons for the choice of Morcar. The rebels were fully aware that the deposition of Tosti was bound to arouse strong opposition, for not only was he a favourite of King Edward but his brothers ruled much of England and the eldest, Harold, was second only to the king. In these circumstances, the wise course for the rebels was to ally themselves with the other major family in England, in the person of Morcar. This alliance would bring them the assistance of his brother, Earl Edwin of Mercia. Such major outside support, which could be vital to the success of their revolt, would not be forthcoming for any local Northumbrian leader. The Vita Eadwardi confirms this point when it says that they chose Morcar ‘to give them authority’ for their actions. This was a rebellion against Earl Tosti, rather than a rebellion against southern government in general.

The northern rebels, accompanied by their new ‘Earl’ Morcar, marched south to press their case with King Edward. They were joined at Northampton by Earl Edwin with the forces of his earldom and some Welsh allies. They had ravaged the countryside on the way south, targeting Tosti’s lands and followers in Nottinghamshire, Lincolnshire and Northamptonshire, all of which were part of his earldom. They were met at Northampton by Earl Harold, who it should be noted clearly came to negotiate as he was without an armed following. He had been sent by King Edward, possibly at the suggestion of Earl Tosti, to open negotiations with the rebels. The intention was that he should restore peace to the kingdom and his brother to his earldom.

Harold was now faced with the most difficult negotiations of his entire career, between two sides equally determined not to give an inch. These negotiations were undoubtedly made more difficult because of the passions aroused on both sides and because they reached into the heart of the kingdom and the heart of Harold’s own family. In comparison, Harold’s earlier negotiations with Earl Aelfgar and Gruffydd of Wales, must have seemed relatively straightforward. On the one hand, Earl Tosti, his own brother, was determined to recover his earldom, even if that meant civil war and the crushing of the rebellion by force. Initially, it appears Tosti was supported in this by King Edward and his sister, Queen Edith. On the other hand, the rebels, consisting of the northern thegns from Yorkshire and the rest of the earldom and led by Morcar, wanted Tosti removed. They were supported by Morcar’s brother, Earl Edwin of Mercia, and the men of his earldom. The initial positions adopted by Earl Harold himself, and by his brothers Gyrth and Leofwine, are unknown, but were presumably supportive of their brother Tosti. Harold’s attitude may be hinted at in Chronicle C, which states that he ‘wanted to bring about an agreement between them if he could’, including presumably Tosti’s restoration. The fact that Tosti may have requested his brother’s mediation and the latter’s later reaction to Harold’s failure to support his restoration may indicate the same.

However, after Harold had spoken with the rebels at Northampton towards the end of October, he realized that it would be impossible for Tosti to retain Northumbria. The latter had completely lost the consensus of support which an earl required to rule. He had succeeded in alienating the majority of the local thegns rather than simply one faction or another. As a result, the feelings of hatred and distrust now stirred up against him were too deep to be assuaged, and the opposition was now too well organized and supported to be overcome without a civil war. The spectre of civil war was something which Earl Harold drew back from, just as his father and King Edward had done during the earlier crisis of 1051–2. Therefore, by the time he returned to Oxford where the royal council was to meet on 28 October to consider the crisis, he had probably already made an important decision.

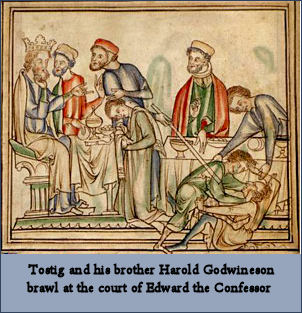

At the Oxford council, Harold announced that the rebels could not be persuaded to withdraw or reduce their demands for Tosti’s removal and that they could only be compelled to do so by the use of military force. He advised against this and instead suggested their demands should be met. The Vita Eadwardi recounts the arguments raised against military action including the fear of civil war and the imminent onset of winter weather. The fear of civil war, as in the crisis of 1051–2, certainly loomed large in men’s minds. Harold himself was also now aware of William’s ambition to invade, an ambition which would more easily have become a reality if there had been civil war in England. Nevertheless, Harold’s statement must have caused shock and consternation for the king, for Earl Tosti, and for the rest of the Godwine family. The king demanded that troops be called out to restore Earl Tosti by force. It seems that Tosti was so stunned and furious that he actually accused his brother of inciting the whole rebellion, with the aim of expelling him from the kingdom. Indeed, so emphatic was Tosti with this accusation that Harold had to purge himself of this charge by swearing an oath.

Is it possible that any truth lay behind Tosti’s accusation? As we have seen, the rebellion had resulted from local causes in the north which Harold could not have created. It is possible that Harold took advantage of the fact of the rebellion to rid himself of a rival or potential rival, but there are no contemporary indications that the brothers were considered as rivals. On the contrary, the brothers had always worked very closely together, particularly during their recent Welsh campaign. In addition, the Vita Eadwardi, written for Queen Edith, is clearly confused by this sudden rift between the brothers, and the whole scheme of the work, based on the brothers working together with a common aim, is disrupted and transformed by it. Similarly, Queen Edith herself is stated to have been confounded by the quarrel between her brothers and there is no reason to doubt this. Therefore, there appear to be no grounds for suspecting any important rivalry between the brothers before 1065.

It has been suggested that Harold now saw Tosti as a potential threat to his designs on the English throne and used the rebellion to achieve his replacement with Morcar. This assumes that Harold already intended to take the throne and forestall the rightful claims of Atheling Edgar, which is by no means certain. It also requires that Tosti would be opposed to such an action by Harold, and that the latter had already prepared an alliance with Edwin and Morcar to secure a possible future move for the throne. In such circumstances he might have sought to win the support of the brothers Edwin and Morcar by supporting Morcar in his claim to Northumbria. However, there are problems with such a scenario. Firstly, there is no evidence one way or the other to indicate when Harold forged his alliance with Edwin and Morcar, and second, it seems unlikely that Tosti would in fact have opposed any move by Harold to take the throne. There is little evidence, for example, that he was a supporter of the rightful heir, Atheling Edgar. The latter is never linked to the earl, although they must have had regular contact at court. The possibility of Tosti himself as a rival candidate for the throne also seems unlikely since as the younger brother, less powerful than Harold and more isolated in the north from the centres of power, his claim could only be weaker than Harold’s. All the evidence seems to point to Tosti as Harold’s potential supporter in such a venture, as in all previous actions.

The timing of the Northumbrian rebellion itself also causes difficulties. In the autumn of 1065 King Edward was around sixty-three years old but had as yet shown no signs of imminent demise. If Harold was making arrangements to occupy the throne already, his actions could have been premature. He might have had to wait for several years for King Edward’s death, by which time Atheling Edgar would have reached maturity and perhaps been in a more secure position to succeed in opposition to Harold. In such an interval, any alliance between Harold and the brothers Edwin and Morcar might decay and the latter be tempted to support Edgar instead. This would also appear to make the suggestion that Harold took advantage of the Northumbrian rebellion to remove Tosti seem unlikely, although it cannot be entirely ruled out. It is impossible to establish the truth of this unless we consider the reactions of the rest of the Godwine family and of King Edward to the rebellion against Tosti.

The sympathy of King Edward and Queen Edith for Tosti is clearly recorded. The positions of Gyrth and Leofwine are unknown but it is possible that Gyrth was close to his brother Tosti as he is frequently associated with him in the sources. Thus he was in Tosti’s company during the family’s exile in 1051–2, and again on the visit to Rome in 1061. In an obscure reference in the Vita Eadwardi, Tosti’s mother, Gytha, would be described as sorrowing over his exile. In spite of this sympathy for Tosti from the king and members of his family, all these individuals were eventually persuaded, probably in part by Harold but largely by the stark facts of the situation, that Tosti could not remain as Earl of Northumbria. Indeed, they were also persuaded that since he refused to accept his deposition he should be exiled. Gyrth and Leofwine appear to have accepted Tosti’s downfall without a murmur, and thereafter supported Harold with complete loyalty until they fell together at Hastings. There are no indications in any sources that either brother considered supporting Tosti instead of Harold and this strongly suggests there existed no suspicion concerning Harold’s actions on their part. King Edward is recorded in Chronicle D as finally agreeing to the terms of the northern rebels. Although the Vita Eadwardi shows that both he and Queen Edith were deeply upset by Tosti’s fall, it nevertheless makes clear that they accepted it, however reluctantly. All of this would seem to indicate that Harold was not purposefully using the rebellion to rid himself of Tosti, but was forced to act as he did as a result of it.

Eventually, King Edward had to accept the northern rebels’ terms. The alternative was civil war, which no one was prepared to countenance. Tosti was deposed and replaced by Morcar, the rebels were pardoned and the laws of Cnut renewed, the latter point no doubt signifying the withdrawal of the additional tax demands. Harold returned to Northampton soon after the council of 28 October to give the rebels surety for this settlement, and the immediate crisis was resolved. Tosti appears to have been outlawed a short time later, possibly early in November, apparently because he refused to accept his deposition as commanded by Edward. This seems clear from his accusations against his brother and his subsequent attempts to restore his fortunes by any means possible. Domesday Book preserves notices of land forfeited by Tosti at this time at Bayford in Hertfordshire and Chalton in Bedfordshire. Thereafter, Tosti took ship with his wife and family and some loyal thegns and sailed for Flanders and refuge with his brother-in-law, Count Baldwin V.