Photo of Bogdan Vasko, commander of the Red Army detachment near Ufa, 1918.

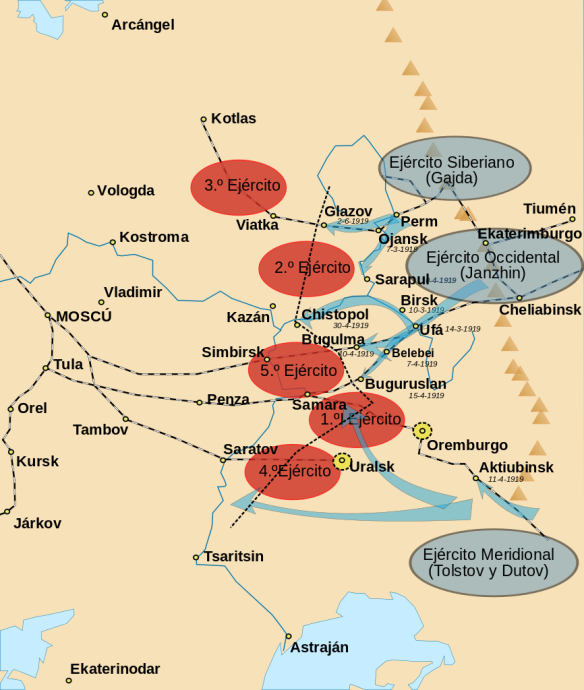

Kolchak’s Army Offensive

The Whites might, on the other hand, have had a much more cautious policy, holding the Urals line and equipping their army behind it. This made sense in purely military terms; it is what Stepanov and Knox wanted. Kolchak might have waited to mount, with General Denikin’s southern White armies, a coordinated late-summer offensive against Moscow. But Denikin’s advance, which took him to Kharkov and Tsaritsyn at the end of June, could not have been predicted, and may only have occurred because Red troops had been moved from south Russia to fight Kolchak.

And there were basic political, psychological, and military factors pushing the Whites forward. Some of their leaders thought the Reds would simply fall apart if attacked – a not unreasonable assessment, given the pressures on Bolshevik Russia from several sides. Whatever Knox’s local advice, Kolchak saw the political necessity of an offensive as a means of getting Allied aid and recognition. ‘Foreign policy was made by the army,’ one of Kolchak’s advisers recalled. ‘On it depended both the scale and continuation of the Allies’ help.’ And underlying Kolchak’s dilemma was the overall balance against him: the Red Army – with its big population base – was getting stronger all the time.

Kolchak’s Ufa offensive was later described by Stalin and a generation of Soviet historians as part of the ‘First Campaign of the Entente.’ In fact there is no evidence that the Allies provoked the March 1919 offensive; the most important Allied representative in Siberia, General Knox, wanted Kolchak properly to prepare his forces before going over to the attack. The March offensive, Knox later reported to London, ‘was commenced without our previous knowledge’; the local British mission had to accept it as a fait accompli. The attack, unlike the 1918 Volga campaign, was a purely Russian affair; the Czechoslovaks, in particular, had been withdrawn to the rear to guard part of the Trans-Siberian railway. There were no Allied troops involved in the fighting. (A handful of Allied battalion-strength detachments were stationed deep behind the lines in Siberian cities, and there was a large Japanese presence east of Lake Baikal.) General Janin, the head of the French military mission, tried to assume command of all forces in Siberia, but this was stiffly rejected by Kolchak on grounds of national pride.

On the other hand Allied, and especially British, logistic support for Kolchak was most important. Rural Siberia had neither munitions factories nor arms depots. The Urals would be the arsenal of the 1941 war, but in 1918–1919 the factories there were in turmoil and starved of food and fuel. Weapons and supplies could only come from outside, and thanks to the port of Vladivostok they began to flow to Kolchak six months before they began to flow to General Denikin in south Russia (via the Black Sea). Knox stressed the British contribution in a letter to Kolchak of June 1919: ‘Since about the middle of December [1918] every round of rifle ammunition fired on the front has been of British manufacture, conveyed to VLADIVOSTOK in British ships and delivered at OMSK by British guards.’ ‘Britmiss’ (the British military mission) reported the arrival between October 1918 and October 1919 of 79 ships with 97,000 tons of supplies. The bulk arrived in Omsk between March and June 1919. Supplies included 600,000 rifles, 346 million rounds of small-arms ammunition, 6831 machine guns, 192 field guns, and clothing and personal equipment for 200,500 men. Kolchak was sent infantry weapons (rifles, machine guns, ammunition) on a scale comparable to that sent to Denikin. (He was, however, sent much less [five times less] artillery, and few if any aircraft or tanks.) One Soviet source spoke of 600,000 rifles and 1000 machine guns from the U.S. in 1918–1919, 1700 machine guns and 400 field guns from the French, and 70,000 rifles, 100 machine guns, and 30 field guns from the Japanese. Whatever the figures, the Allies, led by the British, sent to Kolchak arms and equipment roughly comparable to total Soviet production in 1919.

But the bulk of British supplies did not begin to arrive in Omsk until after the Ufa offensive had started. And there would be great problems throughout 1919 in ensuring the flow of weapons. There was hardly anywhere on the globe that was less accessible than Kolchak’s battle-front. Vladivostok was far from the military depots of western Europe and North America. And even then it was a trip of four to six weeks from Vladivostok to Omsk via the single-track line of the Trans-Siberian, a route dependent on Japanese good will and vulnerable to the looting of local leaders such as Ataman Semenov.

The Kolchak army, officially called the ‘Russian (Rossiiskaia) Army,’ was large by White standards. Kolchak’s commanders realized, however, that Siberia could not match the Reds in overall numbers and that quality could prove the key factor. Vatsetis later explained the initial success of the Ufa offensive by the Whites’ better officers and better disciplined and standardized forces. But the overall quality of Kolchak’s army was never very good, and in particular was below that of Denikin’s ‘Armed Forces of South Russia,’ which had the advantage of a larger pool of experienced and capable generals and colonels, and the officer-veterans of the ‘Ice March.’

Lebedev Dmitry Antonovich (1883-1926) the Colonel (1917). The General-major (11.1918). Siberian military school (1900). Mihailov artillery school (1903). Nikolaev academy of the Generall Staff (1911). The participant of the Russo- Japanese War 1904-1905. April, 22, 1915 awarded with St George cross for Zimgrod defensive operation A member of the Main committee of the Union of officers , 1917 Arrested by Red Revolutionaries in Nov 13, 1917,but escaped from prison, Then join Kornilov’s army, sent out to join Kochack’s army to Siberia. 18 November 1918 year – Commander and the head of general stuff of Kolchack White army in Siberia. 6 January 1919 General-Major. 23 May 1919- military Minster. 12 August 1919 lost his minister’s rank after Cheljabinsk operation failed. Estonia in 1920 and served in Estonian army in the same rank of General-Major. Professor 1921-1926 till his death in 1926 year(due to the wounds received in WW1).

Kolchak’s defeat is often explained by his admiral’s ignorance of land warfare. On the other hand Kolchak had been a very capable and energetic admiral; he was a distinguished combat officer in both the Pacific and the Baltic, and had been selected for early and rapid promotion (he was only forty-five in 1919). In any event, while Kolchak was nominally Supreme Commander-in-Chief, the day-to-day command army was in the hands of his chief of staff. But it is just here, in his choice of subordinates, that Kolchak is most easily criticized. The de facto commander of Kolchak’s armies from November 1918 to June 1919 was General D. A. Lebedev; Lebedev was a thirty-six-year-old wartime colonel who, although a General Staff officer, was better at political conspiracy than high command. Kolchak installed Lebedev in place of the Directory’s competent commander, General Boldyrev, and passed over a number of other qualified officers. Perhaps Kolchak preferred him to a more senior man who would have challenged his own authority; in any event the poorly thought out spring campaign showed Lebedev to have been a bad choice.

Other aspects of the army’s command left much to be desired. The administrative staffs in the rear were too big, which made them ponderously inefficient and starved the active units of officers; Kolchak’s ‘Stavka,’ the former headquarters building of the Tsarist Omsk Military District, was described as a ‘military anthill.’ In addition, the quality of Kolchak’s officers was not high. There were 17,000 of them, but only 1000 had been pre-1915 cadre officers with training and experience in mobile warfare; the great mass were young ‘prapory,’ wartime ensigns (praporshchiki). None of Kolchak’s corps or division commanders had been prerevolutionary generals; the only ‘proper’ general active in the fighting of March-June 1919 was Khanzhin. Lebedev and Stepanov, commanders of the front and the rear, were former colonels in their thirties. ‘Lieutenant General’ Gajda, Commander-in-Chief of the other main front-line force, Siberian Army, was twenty-seven and an NCO deserter from the Austro-Hungarian Army. Of the other best-known Kolchak commanders Sakharov was thirty-eight, Kappel was thirty-six, and Pepeliaev was twenty-six. So in terms of experience there was little to choose between White and Red armies.

Kolchak was never able to make use of what might have been a major asset, the cossack cavalry. Cossack brigades were attached to each White corps but made little impact before September 1919; there was nothing like the successes of the Don Cossacks or the Mamontov raid on Denikin’s front. Kolchak’s potential cossack strength was much less than Denikin’s. The front-line Orenburg and Ural Hosts, with total populations (men, women, and children) of 574,000 and 235,000 respectively, were considerably smaller than those of the Don (1,457,000), the Kuban (1,339,000), and the Terek (255,000). In the steppe south of Omsk was the Siberian Host (114,000) but this was mobilized – incompletely – only in August 1919. The 58,000 Semirechie Cossacks were tied down in Central Asia. (The 258,000 Transbaikal cossacks and 96,000 Amur, Ussuri, and Irkutsk cossacks were in eastern Siberia; with leaders such as Semenov and Kalmykov they were more a liability than an asset.)

The quality of Kolchak’s rank and file was not high. He avoided older World War veterans, from a fear that they had been radicalized by the revolution. Instead he called up the youngest ‘classes,’ nineteen- and twenty-year-olds who had not been ‘infected.’ These men had to be trained (unlike the veterans conscripted by the Reds). The main French adviser thought they were puny, and drily compared them with Jules Verne’s hero: ‘the population of Siberia, particularly in the east, is rarely the Michael Strogoff type.’ Wide use was also made of captured Red soldiers, who were most unreliable. The White army began to fall apart once the Volga advance was stalled. As it was pushed back across Ufa province there were large-scale desertions and even mutinies. By the time Western Army had retreated to the Belaia its strength had fallen from 62,000 to 15,000.

In March 1919 Kolchak’s armies were the largest anti-Bolshevik forces, with a paper front-line strength of 110,000 men. (Total strength – combatants and non-combatants – grew from 160,000 in November 1918 to 450,000 in June 1919.) Siberia had been under White control and free of serious fighting since midsummer 1918; in contrast Denikin and the Don Cossacks were fighting for their lives right through the winter 1918–1919. On the other hand Kolchak’s population base was small, relative to the size of his territory and the strength of the Reds. At its greatest extent the White zone in the east – including the Urals, Orenburg, Siberia, Kazakhstan, and the Far East – contained about 20 million people. In the crucial central zone between the Urals and Lake Baikal, where Kolchak had fullest control throughout 1918–1919 (Tobolsk, Tomsk, Enisei, and Irkutsk Provinces), the population was less than 8 million.

The population of the Soviet-held zone, on the other hand, was 60 million. The total strength (combat and non-combat personnel) of the Red Army in January 1919, two months before the Kolchak offensive, was 788,000, with 120,000 in Eastern Army Group and 147,000 in the Iaroslavl, Ural, and Volga Military Districts behind it. The combat strength of Eastern Army Group in February 1919 was 84,000, and there were another 18,000 combat troops behind it in the three military districts. At this time the Reds had 372 guns and 1471 machine-guns in Eastern Army Group (plus 184 and 231 in the three districts), compared to Kolchak’s 256 guns and 1235 machine-guns.

Meanwhile, after Kolchak’s Ufa offensive, the Reds began to channel resources to the east. Special theses of the Bolshevik CC in early April said that Kolchak’s victories were creating ‘an extraordinarily threatening danger for the Soviet republic’ and demanded maximum effort. Fortunately for Moscow the situation on the other fronts appeared good in April; the French had withdrawn from the Ukrainian ports and the Don Cossacks were under siege; Trotsky could announce in April that Kolchak was ‘the last card of the counter-revolution.’ (At the start of May Vatsetis told Lenin that all reserves were being sent to Eastern Army Group.) By mid-May the total strength in Eastern Army Group was listed as 361,000, plus 195,000 in the Iaroslavl, Urals, and Volga districts. The Reds, then, had large reserves of manpower, Kolchak did not.

In May 1919 one White officer visited Ufa, which stands on a hill above the Belaia River, and looked to the west.

Beyond the Belaia spread to the horizon the limitless plain, the rich fruitful steppe; the lilac haze in the far distance enticed and excited – there were the home places so close to us, there was the goal, the Volga. And only the wall of the internatsional, which had impudently invaded our Motherland, divided us off from all that was closest and most dear.

But it was not to be. Kolchak’s Ufa offensive failed. After two months of success his armies found themselves back where they had started. They would never again threaten the Red heartland, and for the rest of their existence would be on the strategic defensive.

If the White armies had actually achieved the intermediate goal of getting back to the Volga (and they would probably have trapped large Soviet forces in the process), they would have had the benefit of a mile-wide river obstacle between themselves and any Red counter-attack, and they might have been ready for some kind of coordination with Denikin’s armies in the south. On the other hand, even if Kolchak had got to Samara and Simbirsk on the Volga in May 1919 he would still have been 500 miles from Moscow, and the Ufa campaign showed the huge difficulties to be overcome. The basic reason for failure was that even the limited task involved was too difficult. By May the Whites had lost the initiative.