SPAD XIII Jacques Michael Swaab, by Iain Wyllie.

The birth of Army aviation coincides with the beginning of all military aviation in America. Following the record-setting flight of Wright and Foulois, during which the Flyer soared to 400 feet and flew at 42.583 mph, thereby satisfying the Signal Corps’ specification for a “flying machine,” the Army accepted the airplane on Aug. 2, 1909. It is this date that properly proscribes the service’s century of aviation activities.

But other starting points are variously cited, even by the Army itself. Professor Thaddeus Lowe’s seven hydrogen-filled balloons won President Abraham Lincoln’s instant approval after a demonstration flight in 1861, and were subsequently employed by the Union Army during the battle for Fair Oaks and the siege of Richmond in 1862.

When the Spanish-American War broke out in 1898, the Army put its only balloon into service. Sgt. Ivy Baldwin was sent aloft on June 30 to confirm the presence of Adm. Pascual Cervera y Topete’s fleet in Santiago de Cuba harbor. The next day, the balloon and Baldwin were in action above Kettle and San Juan hills, messaging target information to Army artillery and Col. Theodore Roosevelt’s “Rough Riders.”

Though the potential of airborne platforms for the military had already been recognized, it would be nine more years until the Army would give further consideration to aeronautics. Army officers who took an interest in ballooning were labeled “balloonatics” – followers of a phenomenon that was nothing more than a new sport. In the meantime, European aviators were forging ahead.

Washington finally began to take notice in 1907 and created the Aeronautical Division of the U. S. Army Signal Corps. It took the foresight of President Theodore Roosevelt to get the ball rolling with regard to powered flight. Aware that the United States was behind, Roosevelt dipped into a special carte blanche “presidential fund,” which had been granted by Congress a decade before for use at the chief executive’s discretion. The money was set aside for the development of the country’s first military aircraft, with specifications laid down by the Signal Corps.

More than 40 bidders sent proposals to the Signal Corps, but the Wright brothers were the only candidates whose application seemed realistic, and their bid was accepted in 1908. The result was a series of acceptance trials held at Fort Myer, Va., beginning in September 1908. Tragedy struck on the last of the initial trials when the Flyer crashed after one of its two propellers cracked. Orville Wright, piloting the airplane, survived with a broken left thigh, cracked ribs, and a gash in his cheek. His passenger, Lt. Thomas E. Selfridge, a cavalry officer, became the first casualty of powered flight and Army aviation.

Fortunately, the crash did not kill the Army’s desire for an airplane, and the aforementioned 1909 flight sealed the deal. But progress from 1909 until America’s entry into World War I in April 1917 was poor. In 1913, a bill that would have established military aeronautics as a separate corps distinct from the Signal Corps reached the House Military Affairs Committee, but died there. Spending on Army aviation since 1908 amounted to only $435,000. Meanwhile, Germany had invested more than $28 million.

On the brighter side, the Army’s first successful standard training plane, the Curtiss JN-1/2/3/4 Jenny debuted in 1915. It would go on to be produced in the thousands, with sales to the Army, Navy, and the Royal Air Force. Still, the Aviation Section of the Signal Corps numbered just 29 officers, 155 enlisted men, and eight airplanes by the summer of the same year.

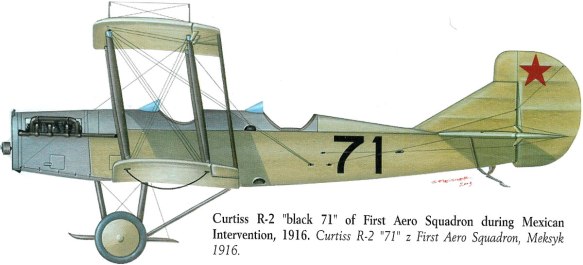

The war in Europe had been under way for almost two years in March 1916 when President Woodrow Wilson ordered the Army to pursue Mexican bandit Pancho Villa and his forces in the wake of an incursion in New Mexico, which led to a battle with the 13th U. S. Cavalry. The Punitive Expedition’s leader, Brig. Gen. John J. Pershing, requested that the 1st Aero Squadron and its eight JN-3s and 11 pilots (including Foulois) be assigned to him for the campaign to help track Villa.

What followed was a fiasco. The eight underpowered Jennies were no match for the 94,000 square miles of the Mexican state of Chihuahua into which Pershing pushed with infantry and cavalry units. The aircraft were damaged in crashes, suffered engine failures, and had difficulty finding any sign of Pancho Villa. Foulois requested replacements, but the Army had none. Less than a month after its deployment to Mexico, the 1st Aero Squadron was recalled to Columbus, N. M., to serve as couriers.

In the wake of the campaign came the realization that the United States was woefully behind in all aspects of military aviation. Just three weeks before America’s entry into World War I, Dr. Charles D. Walcott, head of the aeronautic committee of the Council of National Defense summed up the situation: “No amount of money will buy time,” he remarked. “Even the most generous preparations would not open up the years we have passed and enable us to lay carefully the foundations of a great industry and a great aero army. We have hardly made a beginning.”

On April 6, 1917, the United States declared war on Imperial Germany and the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Army aviation had on strength just 52 officers and 1,300 enlisted. Only 26 of the personnel were fully qualified pilots and the total aircraft inventory numbered 55. Pershing complained bitterly, “Fifty-one were obsolete and the other four obsolescent.”

Over the summer, Congress and Wilson approved a massive funding increase ($640 million) for the Aviation Section. One of the first efforts mounted was to build an American engine capable of powering the British-made De Havilland DH-4 day bomber, which Pershing had decided would be put into production for the Army’s aviators. Thus, the Liberty engine was born. But the first American-built DH-4 did not reach Europe until March 1918.

After delays, the 1st Aero Squadron sailed for France in August 1917. All the while, Pershing, commander in chief of the American Expeditionary Force (AEF), had been laying the groundwork for Army aviation’s role on the Western Front. His top lieutenants in organizing the force were Lt. Col. William Mitchell and newly promoted Brig. Gen. Foulois.

Volunteers for pilot training abounded (more than 40,000 applied), but few facilities existed to train them stateside. Accordingly, many were trained by the British, French, and Italians. Attrition was huge, and by the war’s end, less than 10,000 Americans were rated military aviators. Final numbers show that only a fraction – 767 pilots, 481 observers, and 23 aerial gunners – actually made it to the front with AEF’s paltry 45 squadrons. Among them were top aces including Capt. Edward Rickenbacker and Lt. Frank Luke Jr. By the war’s end in November 1918, operational U. S. aircraft comprised just 10 percent of the Allied total. Americans had carried out 150 bombing missions, downed 781 enemy aircraft – and lost 289 of their own, including 237 airmen.